A compare-and-contrast between the Hindustani and Carnatic instrumentalists can pluck notes of uncanny overlaps

By when Chitti Babu was six years old, Annapurna Devi had become a mother. When noticed in isolation, this might imply the two musicians belonged to different generations. It wasn’t so.

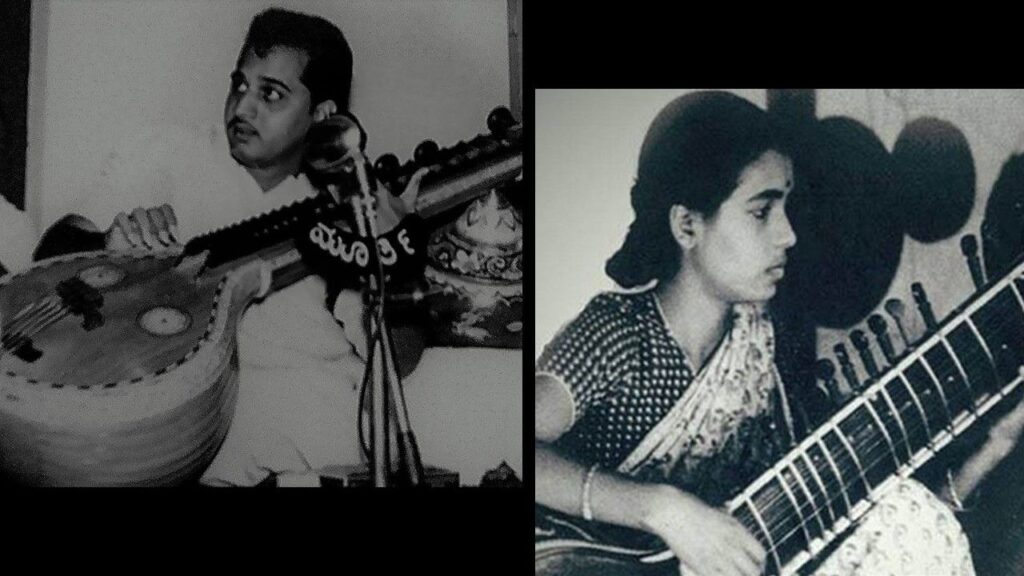

Annapurna was just nine years elder to Babu. And they never met each other despite being renowned figures in their art. Annapurna was an iconic 20th-century player of the bass sitar called surbahar, while Babu excelled in another string instrument called the veena. Both were vital figures in their chosen slot of classical Hindustani and Carnatic idioms respectively.

The passing of October prompts music lovers to particularly recall both the titans. The two were born on the same date: the 13th of the month. Annapurna in 1929 and Babu in 1936.

Least keen to go for an overall view, the joint tribute seeks to line up some of the interesting, if unique, highlights of the two musicians.

Guru Ma

An unlock in India these days amid Covid-19 follows a nation-wide shutdown that had detained us indoors for long this summer. Even into the end-monsoons now, human movements face several restrictions being clamped in a bid to check the pandemic.

If such an experience, however prolonged, is new for the people, Annapurna’s case should leave us in awe. The musician spent five decades indoors, least keen to go out. Her withdrawal, of course, was triggered by a chain of bitter real-life episodes that climaxed with her divorce from globetrotting sitarist Ravi Shankar. Annapurna’s flat in upscale Mumbai was rarely open to visitors. Those who managed to get an audience were from the world of music—prospective students or buffs.

For the learners, Annapurna gave a shock. Not with her disciplinarian mode, but by giving even disciples with fairly long experience that (s)he has imbibed only a drop in the ocean of music.

Flautist Nityanand Haldipur, for instance, recalls his first meeting with Guru Ma. A Mumbaikar, Nityanand was 38 years old when he became a pupil of Annapurna (after 13 years of persistent requests). Raga Yaman, very common in the system and one Nityanand thought was among the easiest to delineate, was the first one to be taken up under the new guru.

Soon after his first few blows into the flute, Nityanand felt he knew nothing about the melody-type. It was like he was a “tiny creature in front of the Himalayas”, he would recall later. “She was a much much superior player to Pt Ravi Shankar-ji. Whenever they played, she used to get more applause. And then, naturally, the male ego is always hurt. Clashes and arguments,” he says, citing the reason for her abrupt end to public concerts (since 1955).

Annapurna legally separated from her long-estranged husband in October 1982. Two months later, she married jovial US-returned management guru Rooshikumar Pandya, her sitarist disciple a good 13 years younger. Pandya died in 2013, and Annapurna five years later.

Interestingly, Annapurna was addressed Ma (mother in Hindi) by her father-tutor Allauddin Khan (1862-1972), the multi-instrumentalist genius.

Babu’s film trysts

In 1973, Bollywood released Abhimaan, a musical drama film themed on the troubled marital relation between Annapurna Devi and Ravi Shankar.

That was the year Chitti Babu won Kalaimamani, a prestigious award by the Government of Tamil Nadu for superior contributions to culture. The artiste (1936-96) from seaside Kakinada in neighbouring Andhra Pradesh had, a quarter century ago, made Madras (later Chennai) his home.

Cinema was what led Babu to move to Madras in 1948. He featured as a leading child artiste in a Telugu movie titled Laija Majnu (starring the celebrated Bhanumathi Ramakrishna and Akkineni Nageswara Rao).

That apart, Babu went on to become a frontline disciple of veena veteran Emani Sankara Sastry, also from Andhra. (Sastry’s native Draksharamam is barely an hour’s drive from Kakinada.) Incidentally, Sastry (1922-87) has had his collaborations with Pt Ravi Shankar (1920-2012), serving audiences with the grandeur of the Carnatic and Hindustani styles on one stage.

Sastry’s school, steeped in a meditative spirit, was thoroughly traditional. The student was more flamboyant in his approach to music. (This, again, contrasted with Annapurna’s art and life.) Babu’s plucking of the veena strings had lesser emphasis on microtones. The breeziness wooed not just a new generation across the Deccan, the instrumentalist also found admiration in the West (he extensively toured Europe and the Soviet Union).

Simultaneously, he carried forward his association with film music. For three decades from 1948, Babu had his trysts with cinema by donning the music director’s role and giving the veena track for the actor’s moves. Annapurna Devi vis-à-vis Chitti Babu is a legacy of introversion versus flamboyance.