Delhi’s Chor Bazaar, renowned as a treasure trove for buyers, also unfolds a compelling tale of bargains and betrayal.

Upon arriving in Delhi in 1989, I began visiting the Daryaganj Book Market every Sunday. I used to spend the whole day there, having my lunch at one of the old restaurants that dotted the area. These included the famous Moti Mahal, whose owners claim to have invented butter chicken, Zaika, the wonderfully named Chor Bizarre, Thugs Restaurant, Bhaja Govindam, and lots of small dhabas selling piping hot bread pakoras, paneer pakoras, and samosas. Most of the above-named restaurants specialised in non-vegetarian food, and I am a lifelong vegetarian. I confined myself to Bhaja Govindam or the dhabas for a hurried bite before attending to the more serious business of trawling for books.

On one of my visits to Daryaganj in 1990, a bookseller casually asked me whether I had visited the Chor bazaar (Thieves’ Market in Hindi). I had never heard of the place and enquired whether it had books. I was informed that the bazaar was held in the vast vacant tract of land behind the Red Fort and that I could find anything under the sun there, including books. Moreover, it was only a ten-minute walk away from the iron over bridge at the end of the Daryaganj market. I immediately made my way there, attracted by the thought of chancing upon a bunch of vintage treasures.

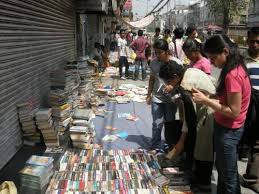

The market was extremely chaotic with makeshift stalls among which a seething mass of people ebbed and flowed. Organized Chaos would be an apt description. There was no particular delineated section where you could find specific goods. Hawkers selling stylish suits and salwar kameezes sat next to stalls with second-hand calculators, PCs, CDs, and game consoles. Stalls with multicolored empty perfume bottles, aftershaves, scratched furniture, mobile phones, and tires and spare parts for every type of vehicle were in abundance. Sports goods like locally made cricket bats and balls, badminton rackets and shuttlecocks, as well as footballs, were freely available.

There were also several carpet sellers and dealers in dubious-looking ‘antiques’. It became clear that most of the goods were damaged, second-hand, stolen, or surplus. The new-looking items on sale were mostly duplicates of well-known brands. The buyers had to have sound knowledge of the goods they were looking for because of the number of authentic-looking fakes that were being sold. One also had to have that one skill every Delhiite needs, to bargain and haggle until a seemingly fair price is reached. It is said that in Chor bazaar, you could purchase an almost new car tire of a reputed brand at one-fourth the actual price, to be used as a spare. On carrying your spoils triumphantly back to your vehicle, you would find that one of your tires has been stolen and the same had been sold back to you. Some bargains.

A treasure trove of books

The area boasted only four or five book sellers. On my very first visit, I snagged around six Whitman Flash Gordon comics in very good condition for the princely sum of Rs 1 each. I also found a number of paperback books at throwaway prices, much lower even than the prices in Daryaganj. I imprinted the location of each bookseller on my mind and became a regular at the market. Every Sunday, I would jostle and wrestle my way through the crowds, keeping a wary eye out for pickpockets, and visit each of the sellers.

On one never-to-be-forgotten day, I found that one of the booksellers had a box full of hardcover children’s books from the fifties and sixties, in pristine condition, including several Enid Blytons, Jennings books by Anthony Buckeridge, and Doctor Dolittle books by Hugh Lofting. This piece of heaven cost me just Rs. 2 per book. Even now, the mind boggles when I recall the incident.

The other wares sold in the market held no interest for me whatsoever. On one occasion, I was pushing my way through the market when my passage was obstructed by a couple of shifty-looking young men, one in a soiled T-shirt and jeans, and the other in kurta and pajama. They were deep in conversation, and the taller of the two appeared to be trying to sell a new and shiny-looking camera to the other.

The guy in the jeans wanted a minimum of Rs. 3000 for the camera which, he said, was left behind by a rich foreigner in the lodge where he worked. I was not in the least interested in cameras and was only half-listening to the conversation. The man in the pajama took hold of the camera and went to discuss the matter with his partner who owned a stall selling electronic goods.

This stall was a few paces down the path and, sidestepping the man in jeans, I continued on my way. When I reached the stall where the other two were talking, they lifted their voices. The man who had borrowed the camera asked his friend the electronics dealer if the camera was any good. The dealer exclaimed, with suppressed excitement, that the camera was the latest Minolta with zoom lenses and all the fixings. He felt that the camera was worth at least Rs. 9,000 and advised his pal to get it for Rs. 1,500. They could then sell it at a princely profit. The friend then took it back to the man in jeans and appeared to haggle with him.

Apparently, the man did not agree as he grabbed the camera back and quickly walked on past me. As I proceeded down the path, he suddenly turned to me and asked me if I would like to buy the camera for Rs. 3,000. I was intent on getting to the booksellers and muttered a curt no and brusquely pushed past him. I did not think much about the incident as I was soon absorbed in the books, and the incident faded into the recesses of my memory.

Unraveling the Con

Several months later at the same place, I was walking behind a well-dressed middle-aged man with a receding hairline and a prosperous paunch preceding him. He appeared to be shopping for electronic goods. I mentally christened him ’Baldy’. Suddenly, a couple of men appeared in his path, and one appeared to be trying to sell a camera to the other. I had a distinct feeling of déjà vu and did a double-take. It was my old friends, and even their conversation was following the same pattern.

Baldy was more attentive than I had been the last time and was following their conversation closely. It was like watching a film reel for the second time. The pajama man, for it was he, grabbed up the camera and walked over to his companion at the electronics stall where they held an earnest conversation making sure that my bald middle-aged friend, who was now near their stall, could hear every word.

The next act followed the script. Pajama Man took the camera back to Jeans Man (he appeared to be wearing the same pair of jeans and obviously had not washed them in the intervening period). They argued briefly before Jeans Man resolutely shook his head, grabbed the camera and trotted past me and the middle-aged bald man. Thoroughly intrigued, I trotted behind the middle-aged man, eager to see the next act. Sure enough, Jeans Man suddenly appeared before the bald man and offered him the camera for Rs. 4000. The price had gone up, it appeared.

Inflation and all that. The follically challenged man seemed to be very interested; after all, you don’t get a 9,000 rupee Minolta for half the price every other day. While they were conversing, I tried to decide what I should do. The con game was obvious now. I had been the target last time, but they had not selected their target well. If the man had been selling a fake set of vintage hardbacks rather than a dumb camera, I might have been hooked. Even then, I figured I knew enough about books to spot a fake when I see one. Now Baldy had been selected to be the patsy.

I reached a decision and patted Baldy on the shoulder. He was deep in conversation with Jeans Man and looked around irritably. I deferentially told him that I wanted a word in private. He gave me a suspicious look. I again muttered it was important and pulled him aside. The Jeans Man sensed that something was up and gave me a hard look. I quickly narrated my earlier experience to Baldy. Luckily that follically challenged dome was home to a quick brain. He caught on immediately, thanked me, and then went up to Jeans Man and gave him a mouthful before quickly moving off. I beat a quick retreat and looking back, saw the terrible trio standing together, looking after us like a pack of hyenas deprived of a plump warthog.

Over the next few weeks, I was careful to give that particular area a wide berth. I also decided to not visit Thugs Restaurant in Daryaganj because that seemed to be the kind of place the Terrible Trio would frequent. Discretion is the better part of valor. I made my way to the booksellers using other paths, and my weekly visits continued until a fateful day on 22.12.2000.

On that day, a terrorist attack by the Lashkar E Taiba took place at the Red Fort. Two soldiers and a civilian were killed. After shooting up the place, the terrorists escaped over the back wall and across the barren land where the Chor bazaar was held every week. As it was a weekday and there was no bazaar, the terrorists swiftly made their escape. The administration immediately shut down the market, and a few of the vendors were relocated to a road immediately adjacent to Daryaganj market.

The others, including the book sellers, moved to greener pastures, and I never saw them again. For the next seventeen years, I confined my visits to Daryaganj, and the Chor bazaar became a fond memory. I understand that the market has now been revived at the old spot, but I doubt whether even the bait of old books would have drawn me back. Better safe than sorry.

Click here to read all articles by Vineeth Abraham.