Paintings and sculptures of the ‘composite animal’ — made of two or more animals or even humans — are quite common in Indian art. Their creators were perhaps trying to say things that couldn’t be expressed by depicting real animals.

Animals have been sculpted on temples in India, and depicted in paintings, including the Ajanta murals. These animals include mythological and natural ones.

But there is another category of animals that are composed of the features of humans or other beings. The image is made up of different beings, such as humans, land animals, aquatic beings and birds. This is composite art.

Explaining composite art

The composite animal is common in Indian art, with artwork being made by juxtaposing human figures, land animals, demons and even aquatics. Such animals are part of Sanchi, Bharhut, Amaravati, Gandhara and Mathura reliefs. Composite art was most popular during the Mughal era. It was widely practised during the times of the Deccan Sultans too. Composite paintings have been produced in Iran and Sri Lanka as well.

Through the composite art, the artist is trying to say much more than possible through the normal artwork, and conveying a deeper meaning of life. The composite animals cease to be seen as mere physical forms — each symbolises a thought or idea that influences the emotion and nature of human beings. Composite animals were a particular feature of Deccan art. Requiring great skill on the part of the artist, the best of these images depict a single animal composed of several others.

Composite horse

Other schools, too, have depicted composite animals. A painting in the collection of the Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad shows a horse and a horned demon-like figure in front of it holding the rein, which is actually a snake. The horse is made up of different creatures. This composite painting is of Bijapur School of the Deccan, made around 1750 A.D.

A Composite horse, Bijapur School, Deccani miniature painting, mid 18th century.

On close examination of the horse, one can see many details emerging. There are two wings of fire originating from the horse’s neck. On the horse’s body, there are multiple beings juxtaposed with one another — a tiger, lion, dog, deer, goat, stag etc., along with a human head. The right foreleg of this composite horse has on it an animal, which is unidentifiable, and a coiled creature. The left foreleg has a deer figure while the right hind leg has a crane-like creature. The horse is standing on a ground full of flowering vegetation.

Another interesting composite animal painting is in the collection of the State Museum in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh. It is a Rajput-style painting depicting a ’pari’ (an angelic figure with wings), leading a composite animal by its leash and a twig with leaves in her right hand.

A horned demon follows them. The cat-like beast has several animals, like the elephant, rabbit, foxes, and camel, painted on its body. There are also humans comprising a sage, a musician and a priest-like figure. The picture seems to cover all the entities in the universe — angelic, demonic, animal, human and vegetal. The composition is metaphorical if one looks deeply enough.

A ‘pari’ holding a composite beast on a leash, miniature painting, Rajput School, 19th century

Understanding Vrishabha-Kunjar

A composite figure of a bull and an elephant —called a Vrishabha-Kunjar — is found sculpted on many temples in South India. The composition below depicts one such composite animal, at the 12th century Airavatesvara Temple built by Rajaraja Chola at Darasuram in Tamil Nadu.

A vrishabha-kunjar, composite bull and elephant image, Airavatesvara Temple, Darasuram, Tamil Nadu, India, 12th century

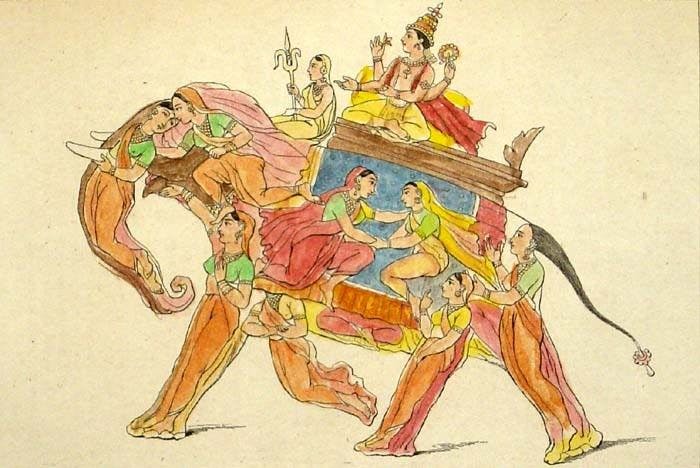

Some composite works depict women painted all over an elephant’s body. Called Nari-Kunjar, such works appear across various schools of painting. The Nari-Kunjar is seen in the terracotta temples of Bengal and also sculpted on the Vaishnava Nambi Temple at Thirukurungudi in Tamil Nadu.

The number of the women who make up the animal is usually 5, 7 or 9 (all odd numbers) The composition below, a coloured engraving, is a Nava Nari-Kunjar, meaning there are nine women who make up the image. One is a mahout holding a goad to steer the elephant. Lord Krishna sits on the elephant and the gopis (cowherd maidens) who were smitten with him during his Vrindavan days, form parts of the beast’s body.

A four-armed Lord Krishna rides on a ‘’gopi’’-elephant, a nari kunjar motif depiction, steel engraving with modern hand colouring, mid 19th century

What do these composite artworks tell us? They represent the unity of all beings and depict inclusiveness. ‘’Composite art represents a new way of finding wholeness and unity,” says Thaneeya McArdle, an online art trainer. “It is a form of creative art that can dissolve boundaries and limitations, propose new possibilities, embrace multiple viewpoints and introduce novel ways of story-telling”.

The paintings depict the greater reality depicted within the body of the animal. These paintings symbolise the interconnectedness of all things, and that we live in a unified universe.

Ghosh is Librarian and Social Media Officer, Salar Jung Museum, Hyderabad. Image courtesy: Salar Jung Museum and Wikimedia Commons. Write to us at editor@indiaartreview.com