Rediscovering Mohiniyattam’s roots; the desi repertoire journey.

I began my career in Mohiniyattam during a pivotal period in the twentieth century when the art form was experiencing a nascent revival. Numerous seminars and workshops were conducted to explore the essence of Mohiniyattam. During these discussions, questions often arose regarding Mohiniyattam’s distinct identity as an indigenous dance form of Kerala. Some scholars compared it to Bharathanatyam, branding it as a lesser sibling that originated from Dasiyattam during the era of Swati Tirunal.

Swati Tirunal played a huge role in sanctifying Mohiniyattam by infusing it with Bhakti and romanticism. This infusion profoundly influenced Mohiniyattam’s evolution. The revival of Mohiniyattam at Kalamandalam in the early 20th century owed much to Swati Tirunal’s legacy. The repertoire during this initial phase included Swati Varnams, Padams, Tillanas, and the Cholkkettu.

The presentation format that took shape at Kalamandalam drew inspiration from the Kutcheri sampradayam, a structure followed in Carnatic music and Bharathanatyam. Certain Mohiniyattam pieces such as Kurathi, Mukkuthi, Poli, Esal, and Chandanam, which may have held more cultural and folk elements of Kerala, were set aside during this revival period.

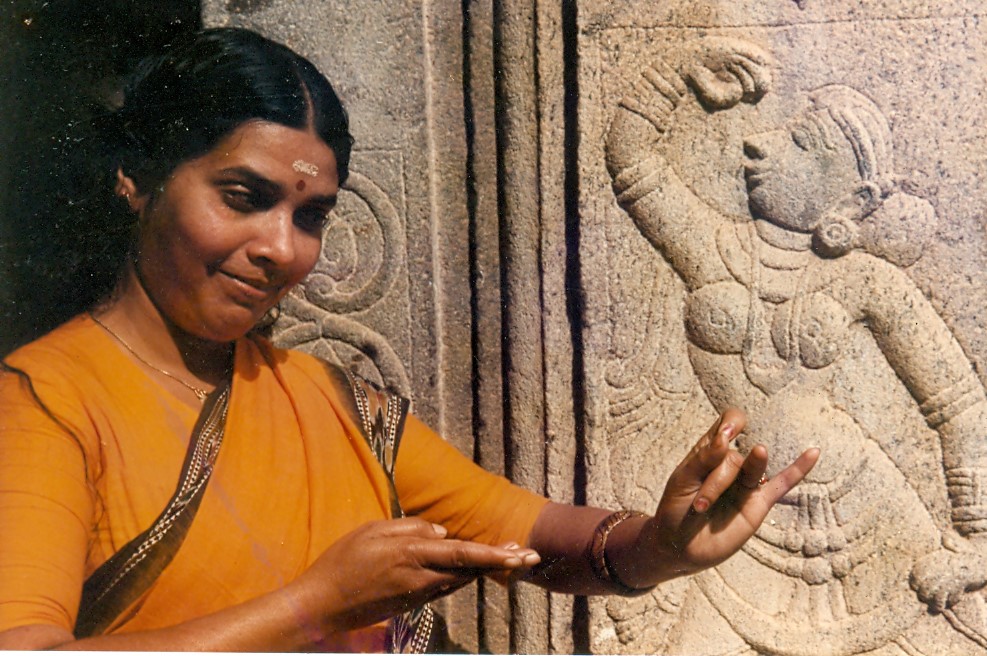

Questions about the indigenous style of Mohiniyattam lingered in my mind, as did inquiries into other female dance traditions of Kerala, such as Tiruvathirakkali and Nangiarkoothu. It was this curiosity that led me to embark on a research journey aimed at uncovering and rejuvenating the roots of a style deeply embedded in Kerala’s cultural, musical, literary, and theatrical traditions.

Mohiniyattam in the late 19th century

By the close of the 19th century, the practice of Mohiniyattam had markedly waned, with many dancers facing financial hardship. The once robust patronage from princely states had dwindled, replaced by local landlords as the new benefactors. Under the auspices of these new patrons, Mohiniyattam performances began to veer from the moral standards upheld by society at the time.

For instance, in the culmination of Chandanam, dancers would approach the audience, applying sandalwood paste to spectators in exchange for monetary offerings or gifts. Similarly, in the case of Mukkuthi, the dancer would diligently search for her missing nose ornament amidst the headgear and attire of the supportive onlookers. These practices bore a striking resemblance to those found in the Devadasi traditions of South India, eventually leading to the British Government’s prohibition of Mohiniyattam performances at a certain juncture.

Hence, Vallathol and the early teachers had valid reasons for omitting such pieces from the Mohiniyattam repertoire. Even after these alterations were implemented, the task of locating both students and teachers for Mohiniyattam proved to be a daunting challenge during those times.

It is crucial to emphasize that the exclusion of these dance pieces does not inherently label them as flawed. Instead, the decline in performance quality can be attributed to the prevailing social circumstances, from my perspective. Through my research, I have unearthed substantial evidence indicating that compositions like Poli, Chandanam, Mookkuthi, and others possess profound connections to ritualistic traditions, folklore, history, and the culture of Kerala. For instance, the practice of presenting Chandanam (sandalwood paste) or Prasadam to spectators by the performer endures in ritualistic performances such as Mudiyettu and Theyyam in Kerala, which have deep-rooted traditions intertwined with the veneration of mother goddesses.

Reviving desi items

My hypothesis is that the female dance traditions that evolved into Mohiniyattam had similar origins in mother goddess worship. And Mohiniyattam pieces like Chandanam could have been part of a traditional repertoire in the distant past.

The desi piece ‘Esal’ depicts the wrangle between Lakshmi Kurathi and Parvathi Kurathy ridiculing each other’s husbands. Lakshmi Kurathy asks Parvathi Kurathi whether her husband Siva killed an elephant for the leather. Parvathi teases Lakshmi by responding that Vishnu killed an elephant to harvest its tusks. Such stories portray our gods with real human emotions that everyone can relate to. The stories may also have the background of Saiva Vaishnava sects that had conflicts in history.

Desi repertoire enabled me to reconnect my Mohiniyattam to its roots. While dance forms should continuously evolve, I think it is also important for any classical style to be anchored to its roots to retain its unique identity, especially in a globalized world.

When Mohiniyattam was revived in the 1930s, the initial focus was more on the Bhakti and Sringara themes which suited exceptionally well for this lasya dance form and became the identity of the dance form. In recent decades Malayalam poetry has inspired many choreographies. That is a welcome novelty and change. On the other hand, the Desi repertoire attempts to reconnect Mohiniyattam further into the bygone past and the acclaimed female dancing and Abhinaya traditions that existed here. The dance form, in my opinion, will flourish if it has both this strong connection with roots and a futuristic outlook.

Any way I practically applied those research findings in my Mohiniyattam choreographies. In the early days, Abhinaya in Mohiniyattam was largely limited to the portrayal of emotions like Shringara and Karuna in the context of Shringara bhakti (madhura bhakti). However, Kerala has female dancing traditions that are rich in Abhinaya and there was opportunity to adapt and adopt it for Mohiniyattam.

In our next article onwards we write about these Desi traditions. While Kerala’s acting traditions have also been influenced by Natyashastra, it probably had different origins. For example, Natyashastra prohibits enacting death on the stage, but detailed enactment of death is done in our Koodiyattam and Kathakali traditions. Similarly, the Ninam (bloodied) characters in our plays are not common in other styles. Such differences encouraged me to research deeper into our acting traditions, especially the female traditions. Our Sangham poetry gives elaborate descriptions of dancers who were exceptional actors called Viralis. They acted with such conviction that their whole body was as expressive as their eyes. Over ages we may have lost all these and Mohiniyattam in the 19th century focussed only on Sringara abhinaya. All these convinced me to work on reviving such a long-lost female acting tradition.

Assisted by Sreekanth Janardhanan

Photo Courtesy : Natanakairali Archives