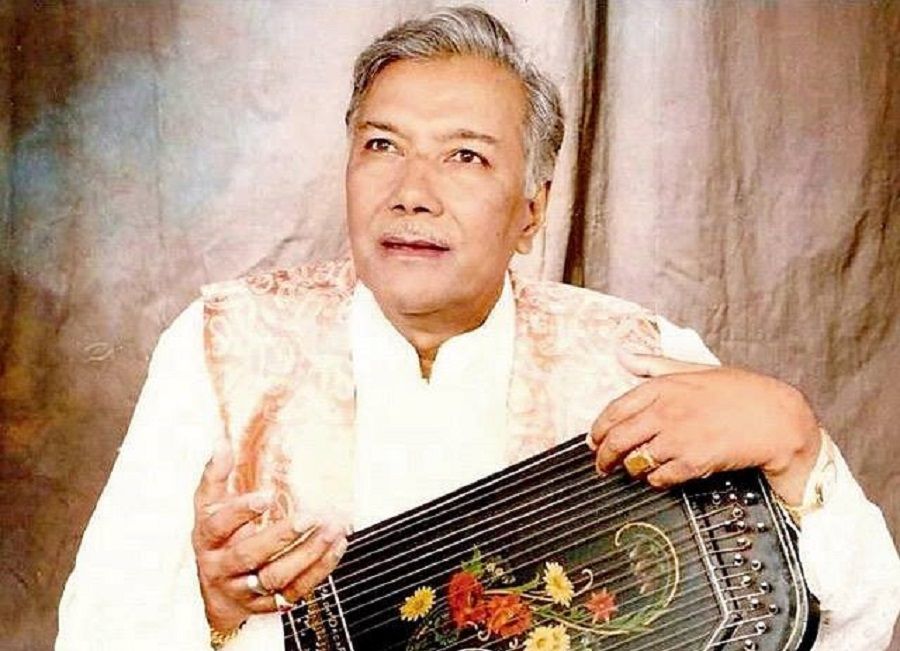

Groomed in north Indian classical, Ustad Ghulam Mustafa Khan (1931-2021) was open to engaging with Hindi cinema as well. The voyage proved symbiotic in more ways than one.

Ghulam Mustafa Khan was really small when his family initiated the boy into music. So much so, he could utter only ya-ya-ya-ya when the elders sang the basic sa-re-ga-ma for him to learn. Nonetheless, the notes sounded fairly perfect. “Music doubled as my leisure as a toddler. In such a way that I didn’t play much with fellow kids even later,” he would recall the childhood in the Indo-Gangetic plains upcountry.

The household’s efforts bore fruit. Khan emerged as a top Hindustani vocalist. Times and lifestyle did change a lot when he died early this week. That was in Mumbai, which Khan had long made his home. A bustling metropolis 1,400 km southwest of where Khan spent his formative years. He would have turned 90 in six weeks.

Khan’s native place was Budaun, which became part of Uttar Pradesh when the state was formed in 1950, three years after Independence. The artiste was a mid-teenager then. “Those days, life was far minimal. There was no electricity even,” he trails off in a 2013 interview to the national telecaster. “One occasional entertainment was the public radio.”

From Akashvani, Ghulam listened to the renditions by maestros. They impressed him deeply. Simultaneously he apprenticed under the seniors in the family with a cultural lineage.

Ghulam’s grandfather was Ustad Inayat Hussain Khan. The legendary vocalist (1849-1919) also played the veena at the king’s court. That was in Rampur — a princely province under the imperial regime. Ghulam’s first guru was his father Waris Hussain Khan. This, when the child was yet to pronounce words clearly, but showed signs of being a promise.

In awe of Darbari, tarana, sargam

Waris Khan ensured that the Ghulam won’t “waste” his time with the same-age children. “In case I was seen with the children of the locality, he would ensure that an elder would drag me back home,” Ghulam Mustafa would reminisce. “Not that my father didn’t love me. He was extremely affectionate. He wanted me to carry forward the family legacy.”

True to the potential he showed as a child, Ghulam Mustafa debuted when he was just eight years old. The occasion was the auspicious Hindu festival of Janmashtami. Badayun, like most Awadh cities of the times, had a Victoria Garden, which was the venue. There, the civic body chief Ali Maqsood used to organise the birthday celebrations of Lord Krishna.

Ghulam Mustafa’s second teacher was his paternal uncle Fida Hussain Khan, who sang at the royal durbar in Baroda. Ustad Fida’s son, Nissar Hussain Khan, next taught Ghulam Mustafa. Nissar (1909-93), too, served Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad in present-day Gujarat.

Alongside the art, Ghulam Mustafa practised two languages: Hindi and Urdu. Music, though, always remained the priority. And enabled Khan to further modify their gharana called Rampur-Sahaswan that pooled in elements from two schools of khayal.

“Our sargam rendition is special,” the exponent used to take pride, referring to the patterned solfa syllables with the ornamental glides and oscillations. “So are our taranas as well. Very flowery.”

What obsessed the ustad was Darbari. It is a raga that grew in the monasteries, dargahs, temples and palaces, he would reiterate. “My guru taught me Darbari at night. In between, he would sometimes doze off. Yet a wrong note from me would wake him up impulsively. And make him ask: ‘What are you singing’!”

Towards film music

For all the traditional way of grooming and keen interest in classical, Khan had a long stint with film music. It began in 1968 when he first sang a song for the Marathi movie Chand Priticha. It was a song that had a streak of the folksy Lavani dance.

That marked the ustad’s start of a lifelong relationship with the tinsel world. These included classics such as Bhuvan Shome (1969) and Umrao Jaan (1981). In the process, the Rampur-Sahaswan gharana, too, earned certain novel modulations. They made the vocals sound sweeter, note experts. Equally, Khan’s contributions to the world of cine music gained value.

“The ustad has always been willing to give us tips. Rather than take anything from us,” says renowned composer AR Rahman, who has collaborated with Khan. Adds frontline playback singer Sonu Nigam, another pupil: “Without the ustad, I would not have become what I am now.”

Iconic popular musician Lata Mangeshkar recalls her meeting with Khan in the last century when her niece Rachana Shah was learning classical under him. “I told the ustad that I suffered certain constrictions in singing certain songs,” she points out. “And he gave me suggestions that proved effective!”

That has been the case with the Padma Vibhushan winner’s sons too — all four of them singers. Also into music are Khan’s two grandsons, Amir Mustafa and Faiz Mustafa. Not to speak of the celebrated Rashid Khan, the ustad’s disciple and nephew.