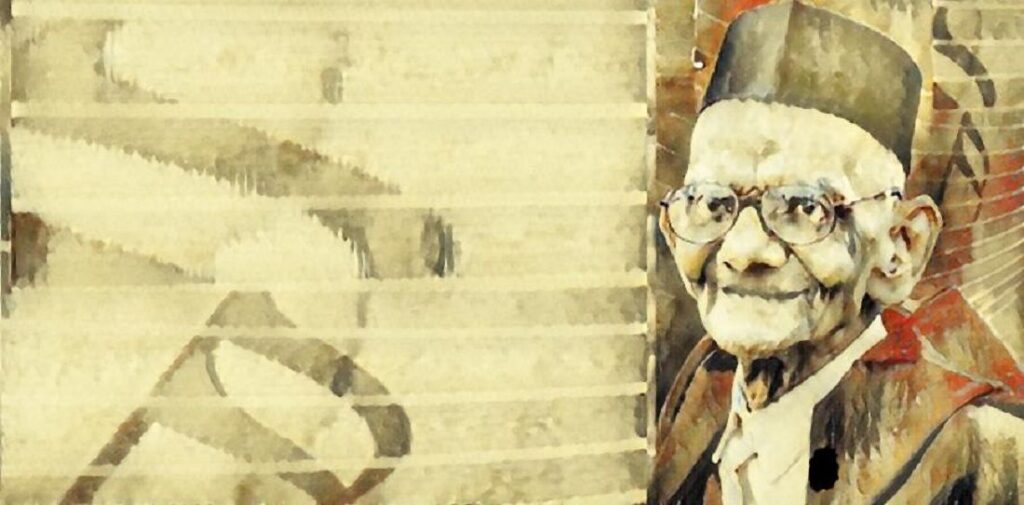

As Hindustani classical music observes the 10th death anniversary of RK Bijapure, a relook at the national broadcaster’s 31-year ban on the harmonium.

Young RK Bijapure was gaining a name as a Hindustani classical instrumentalist when All India Radio suddenly banned the harmonium.The broadcaster’s order came in 1940, and Bijapure was just 23. Only a couple of years ago had the prodigious master started a harmonium school in his native Deccan.

The countrywide ban lasted three decades. All the same, Bijapure’s Sri Ram Sangeet Mahavidyalaya in Belgaum went on to groom more than 10,000 students till the master’s end in 2010.

Even after the lift of the ban in 1971, the harmonium continued to be forbidden in certain stations of All India Radio. For instance, into the 21st century, a Baroda-based cultural organisation reiterated its request to end the AIR bar in Gujarat. This, even as the temple town of Palitana in the state produced arguably the best of India’s harmoniums.

So what led to the ban? How and when did the western instrument enter Indian lands and find a place on its classical music map? A look today into these slices of history, as November 19 is the 10th death anniversary of iconic Bijapure.

Harmonium’s European genesis

The harmonium earned its standard form in 1840 and in the West. This marked a grand culmination to half a century’s history of certain forerunners to its distinction as the first free-reed organ that produces sound when air flows past a vibrating piece of thin metal in a frame.

German doctor-physicist-engineer Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein of the 18th century has been credited with its design. Serving as a professor with the University of Copenhagen, he derived it from the regal as a portable organ popular during the Renaissance.

In 1810, European Gabriel-Joseph Grenie exhibited an expressive organ. The culture buff called it orgue expressif and demonstrated its capacity for a crescendo and diminuendo. Three decades thence, fellow French Alexandre Debain improvised Greine’s invention. The patented version, named harmonium, subsequently spread out of Paris.

A mechanic at Debain’s factory took the instrument to the American shores. He added features to it. Into the mid-1880s, a music instruments company in Boston began to manufacture the harmonium with the suction bellows. Soon it replaced the pipe organ across the churches and chapels of the world. However, the harmonium’s global vitality declined by the mid-1930s following the invention of the electric organ.

Indian entry of the harmonium, and the ban

The harmonium in the Indian subcontinent didn’t script a short wave of popularity. In fact, a decade before Mason and Hamlin of Massachusetts began selling the instrument in 1885, Calcutta musician Dwarkanath Ghose came up with its hand-held version. Ghose’s harmonium spelled an end to the foot operations of the instrument, reducing its size to half of the European original that had come to Bengal through the imperial British.

Ghose (1847-1928) went on to add drop-stones and scale-change to the harmonium. The modifications suited its use in Indian classical music, which banked on melody instead of harmony in the West. More companies began manufacturing the instrument. By 1915, India was a leading producer of the harmonium.

Yet, a quarter-century later, AIR banned it. The reason, paradoxically, was the multifaceted Rabindranath Tagore, a Nobel laureate known for his love of the arts of the Orient and Occident. Initially in awe of the harmonium, he found it unable to produce the oscillating gamaka notes. In early 1940, the litterateur wrote to AIR Calcutta wanting the harmonium’s abandonment in the studio. The request was accepted.

Around the same time, a senior AIR official himself shared Tagore’s view. John Foulds, who headed the Western music wing of Akashvani, believed the harmonium was mute on microtones that were so essential to Indian classical. Lionel Fielden, as the Controller of Broadcasting, agreed.

AIR banned the harmonium on March 1, 1940.

Musicologist Abhik Majumdar says art historian Ananda Coomaraswami and even Jawaharlal Nehru as a freedom fighter found the harmonium un-Indian. The ban on the instrument, Majumdar adds, sustained after Independence owing to the attitude of Information and Broadcasting Minister BV Keskar, a student of scholarly vocalist VN Bhatkhande.

Bijapure’s forays

Born as Rambhau in Kagwad off Belgaum in what is north Karnataka today, Bijapure began as a vocalist. A throat problem led him to specialise in harmonium, which he learned from three masters around Dharwad. Simultaneously he took lessons in vocals. The sessions helped him develop a gayaki ang in Hindustani harmonium.

Besides giving solos, Bijapure accompanied stalwarts of six generations of vocalists. His disciples at the Mahavidyalaya and outside of it gained eminence as harmonists. The awards Bijapure won are numerous.

Today, the harmonium in India thrives in a range of systems: Hindustani, Carnatic, Qawwali, Ghazal, Bhajans, church choir and Sikh gurbani besides several traditional and folk music. Even so, solo harmonium concerts continue to be rare on AIR.

You May Also Like: Annapurna Devi & Chitti Babu: No Heads or Tails