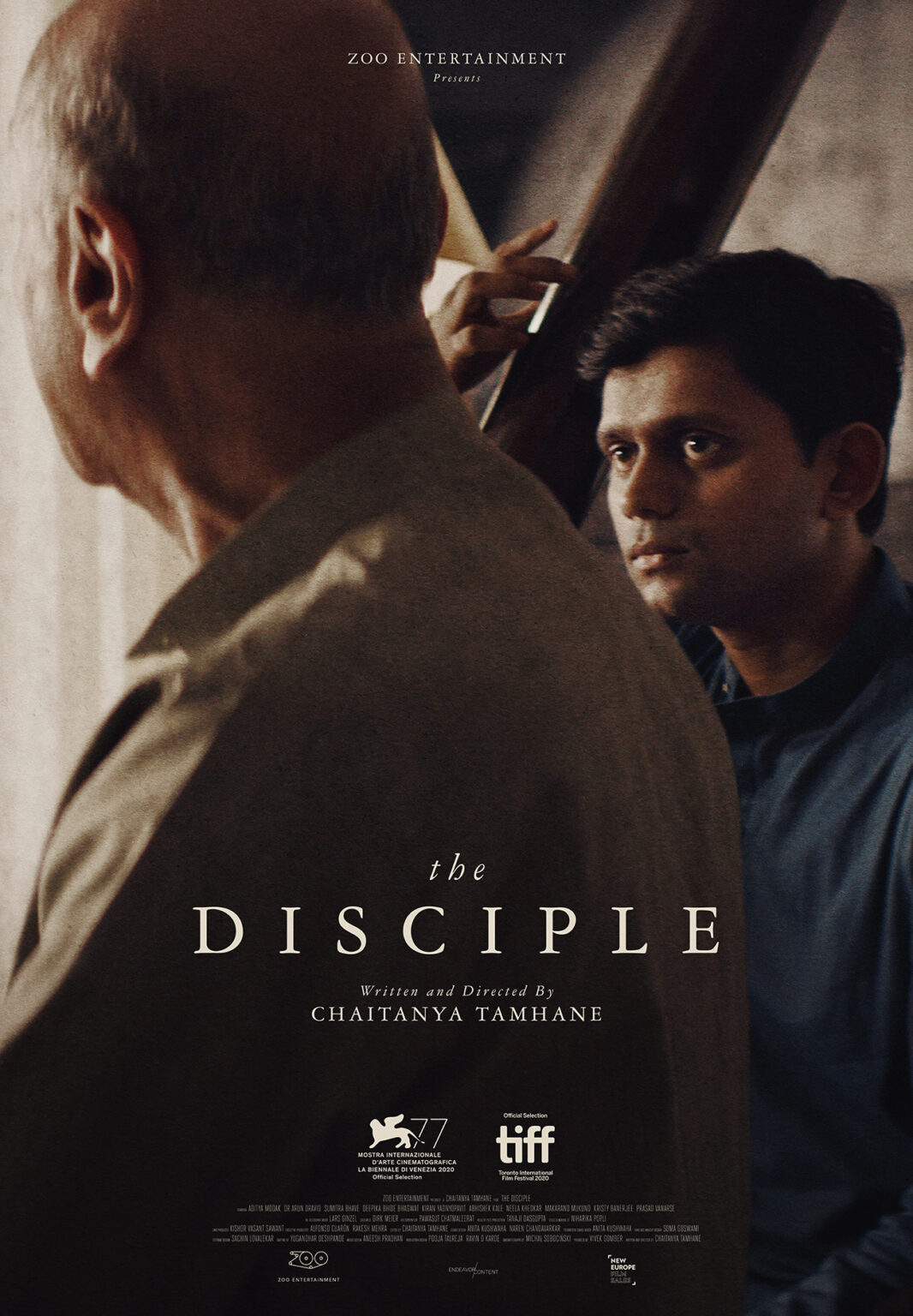

Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Disciple explores the burden of self-expectation and the price one pays for a perceived notion of mediocrity.

Chaitanya Tamhane’s The Disciple, released in May 2020, charts the life of Sharad Nerulkar (Aditya Modak), an aspiring classical vocalist in the Hindustani music tradition. Sharad is a devoted learner under his guru who trains young minds in music while giving vocal performances that earn him his modest survival.

While the other students learning under the Guru along with Sharad find themselves platforms for performance as they graduate, Sharad seems to be struggling, caught up in mere technique and finding it difficult to creatively breakthrough into the art itself. Sharad is fully aware of his shortcomings. He is self-critical, hardworking and, yet, an unsuccessful individual. In such a narration, the film, as largely understood by most, is about “coming to terms with one’s own mediocrity”.

What lies behind the appeal of the film is Tamhane’s ability to produce empathy towards a deeply undesired human value: mediocrity. Whether you want it or not, the film brings an element of doubt in our abilities. This production of ambiguity is the hallmark of Tamhanhe’s film-making, in techniques as well as storytelling. The sustained long-distance shots in the film don’t try to direct the eye too much, but rather suspend the viewer in the ambiguity of space itself.

The illusion of perfection

The voice of the inner mind — in Maai’s recordings plugged into Sharad’s ears as he strolls through the empty streets of the city at night, or his own confusion trying to come to terms with his perceived shortcomings or the seeming politics of his relationship with his guru — create the haunt of ambiguous space. The constructed silences amplify the frustrations of a mind that is unable to articulate the means to reach the genius.

To be sure, the storytelling in The Disciple has the exact opposite effect of what Taare Zameen Par (directed by Aamir Khan and Amol Gupte, 2007) had on us. In contrast to how we all relate to the young dyslexic boy in TZP and imagine that we are special too, Sharad’s character in The Disciple is quite anticlimactic.

Tamhane forces us to consider through the film whether the figure of the genius is reality or myth. What triggers the failure of the disciple in the film? His shortcomings? Or lack of opportunities?

Such opportunities are controlled by networks, connections, access to people, and so on. To be fair, the disciple, Sharad, did not seem so bad. He had the technique, skill and he was intelligent enough to understand his limitations. Then why should he have suffered? To know what you don’t know is a good thing, but did the idealism of his Maai pull him back from believing in himself to even find an alternative space for his craft?

Sharad ends up giving so much importance to the aura of the world that Maai creates for him, that he stops acknowledging his reality, the context in which he lives. Perhaps, the slippage that he suffers in his life is the burden of self-expectation.

What could have been the role of the guru in shaping a student such as Sharad who is honest, hardworking, self-critical yet unable to design music through his craft? We do not see the guru’s efforts in devising methods for his student to be able to produce new experiences or overcome his mental block. While the incapability of the student has been highlighted throughout the film, the responsibility of the teacher could have been detailed too. The pedagogical zone of music is left mythically illusive, excused in complete devotion, abstinence or sacrifice. Sharad refrains from worldly pleasures until a late age despite having strong carnal urges.

The idea of success

The film forces one to look at ‘mediocrity’ as a social construct. How must one prepare a frame for critical appraisal of averageness? The ‘everyday’ is a category that may be one window to the acknowledgement of being average – which is neither good nor bad. Isn’t that what average is? Average is functional, workable, acceptable, and satisfactory. Sharad was satisfactory. For most of our lives, we consume what is satisfactory. The desire to be exclusive and special is a socially constructed desire. I don’t mean to suggest that one should not have the desire to feel special or be exclusive.

The argument however is, why does ‘average’ bring discomfort to us even if the majority of the population is just plain average? How have we come to ascribe a negative value to being average? Is there no beauty in the average? It is the rejection of the average that Sharad’s mind is conflicted with. Sharad’s conflict may also be seen as valid because he has been putting in tremendous personal resources to go beyond the average. Yet, I wish the guru was able to help Sharad reconcile with his averageness. Over time, the film expresses the aesthetic of mediocrity rather beautifully.

Sharad – once a young charming boy reluctantly hopeful of a bright future in his eyes slowly emerges into a stiff middle-aged man drowned in the seriousness of life and failure of his ambition. He is certainly not progressive and holds the values he has come to believe in (without critical consideration) rather strongly. That mindset becomes his frame to judge the world, a world that he feels judged by.

Sharad is confused about the idea of success – he is unable to resolve whether it is the worldly acknowledgement or the internal contentment through his singing that will satisfy his restiveness. In his case, perhaps these categories are intertwined and interrelated. His belief in a purism that he could not bring in his music never deters him from it. Still, Sharad does not alter his route from the Hindustani classical form despite having tremendous technique. He prefers to remain in limbo without the methods or means to achieve success or salvation in his art. This, in my mind, was my biggest dejection in Sharad.

Beyond benchmarks

A stronger Marxist analysis of the film would bring out how values of mediocrity or averageness, which often become the frames of self-identification, are a result of the political economy of how the enterprise of classical music organizes itself in the present-day context. Matters of exposure, access, patronage, and support are all reworked through distinct mechanisms of the economy. Value is largely created through quantified logistics.

How do we trust instruments of TRPs or the uninformed ears/eyes that hold the power to bring value to artistic pursuits that take a lifetime to be honed? The mysticism associated with the values of the ‘genius’ or ‘excellence’ may operate well in a medieval economic model, however, when brought into the space of capitalism may require new grounding.

Yet, the question of where do we locate art, its purpose – for the self and the world, are questions that the film helps open up. The film could have exposed us to other dimensions of Sharad’s life beyond music, which in its portrayal not only makes us view him as a loser, but could also help us enjoy the fact that average is beautiful.

Write to us at editor@indiartreview.com