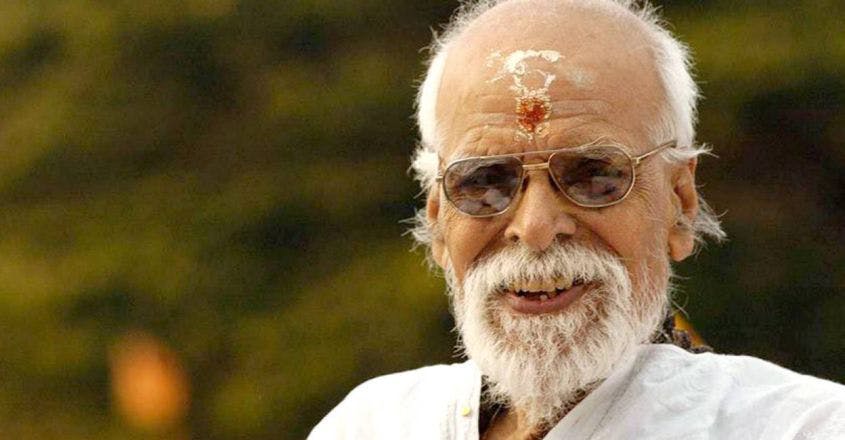

Legendary composer V. Dakshinamoorthy, who gifted more than 1400 songs in Malayalam, Hindi and Tamil was instrumental in pioneering classical music-based film songs. December 9 was his remembrance day.

He strode like a colossus for four long decades and more. His baton shaped the destiny of film music and also that of playback singers. People accepted his innumerable melodies attired in the garb of classical music, wholeheartedly and showered encomiums and eulogies. The delectable style of music that came to stay in Malayalam cinema was very much V Dakshinamoorthy’s expression.

A precocious child that he was, Swamy, as he is known, could sing 27 Thyagaraja kirtanas at the age of seven. His debut concert took place at the age of 13.

He attributes his musical ingenuity to his guru Venkitachalam Potti of Thiruvananthapuram and Lord Vaikkathappan to whom he offered musical oblations for three and half years at the rate of 18 hours a day. “My guru poured out bountifully and asked me to do so to my disciples”, he recalled. Further, sing in concerts as though you are the composer of each kriti, he had advised. Perhaps the inventive brilliance that characterizes his creations and an abundance of classicism, the hallmark of his concerts, could be imputed to this aspect.

Even though a short stint in filmdom occurred in 1942 — he scored music for the ‘first time for the Tamil film Manorama at Ratna studio, Salem — Swamy turned a regular composer only since 1948 when he settled in Madras. Through Avan varunnu, Kidappadam, Jeevitha naouka, Anna, Jnanasundari and the like melodies flowed uninterruptedly and spontaneously. “I believe lyrics make 60 per cent and music only 40 per cent of a song”, he said even as he bemoaned the practice of straight jacketing lyrics to precomposed score. The feelings of the lyricist found expression through his verses according to him and they inspired him to sing out the tune as though a product of his intuition. And in this exercise, he banked only on his vocal cords for, “I do not know how to play any instrument, even a harmonium”!

Even hard and prosy verses turned supple once they were set to musical notes and in this respect his dexterity was unparalleled. “Are you so cruel to score music even to prosy texts?” Jagathy N K Achari had asked him on hearing the lines of Kavalam for Kurukshetram Njanum, anujanmmarum, ee naadum’ as rendered by Swamy. P. Bhaskaran once complimented him, “Swamy, you can score music even for a calendar”.

An Avant-garde musician

Film music falls in the category of ‘applied music’. It requires the genius of the rarest kind to accomplish this challenging job. Perhaps the monumental contribution of Swamy has been to reach classical music to the masses through the highly influential medium of film music. Ragas were selected, very often mixed and those of the standard kritis changed all to highlight the mood of the situation.

Today when mohiniyattam dancers perform to `Aliveni enthu cheyvoo‘, the alluring Swathi padam in Yadukulakamboji, set by Swamy in Gaanam, they seem to have forgotten the original raga of the composition, Kurinji. Similarly, Karuna cheyvaan enthu thamasam Krishna received a different dimension from Swamy in the same film.

While Vidarunna killimozhiyodehad to be mixed in Kappi and Gourimanohari, the comedy song in Sreekovil Naagaraadi enna undu had to be given a vivadi note in the avarohana of Yadukulakamboji. “This note would never occur to the vocalist, and I myself had to sing for recording”, he reminisced. ‘Easwaran manushyanai avatharichu‘ in Sreeguruvayurappan began in pure Mukhari but soon lost the essential feature of the raga in the charanams because,” Mukhari is considered inauspicious in films”.

Harmonizing each note of a raga except in Sankarabharanam needs extra care but Swamy achieved this in his own esoteric style. He never cared about the `major’, ‘minor’ or ‘seventh’ chords, the jargon of the artistes in the studios; harmony occurred to him quite spontaneously as a combination of consonant notes. “Listen to the long notes of shadjam and panchamam played on the nadaswara in ‘Pon veyil mani kacha azhinju veenu‘ “, he explained.

“All my children are handsome”, he boasts of his creations, But he can hardly identify or estimate their total number. Recently Devarajan took the pains of collecting all those done by Swamy from 1972.

Tryst with literature

Interestingly, Swamy turns a deaf ear to either his music or the music of others as played through radio or any medium. And he holds this the secret of the originality of his compositions. Very often a haunting melody, accidentally heard, would compel him to ask his children about its composer. Invariably it happened to be him!

Dakshinamoorthy holds the rare distinction of having re¬corded three generations of musicians. Augustine Joseph with whom he worked in theatre, Jesudas and his son who sang a verse in Edavazhiyiloru Kaalocha. And the Guinness folks are just round the corner.

His prodigious output in music has been equally matched by his literary outpourings. Hundreds of devotional couplets have been written in chaste Tamil and Sanskrit – languages he never learnt. A collection of Tamil verses has been compiled as a book named Aatmadeepam. This has been hailed as an outstanding work in Tamil.

Swamy claims these to be products of the sublime level of spirituality he has attained over the years for which music has been the means. And in this respect, he is very much an incarnation of Saint Thyagaraja. The resemblance becomes more striking when Swamy clarifies to know “when and where I will breathe my last”.

As he sings sitting in front of the model of Vaikkom Mahadeva kshetram that decorates his drawing-room, one notices that the voice is still young and the style rendition, bewitching. And a familiar style for that matter since it has been faithfully copied by the outstanding playback singers of today.

But one can hear also the echo of some discordant notes – notes of reproach – when he repeats, “I have not stopped doing music”.

(India Art Review is republishing a series of vintage articles on yesteryear stalwarts. This article was written by G S Paul in 1993.)