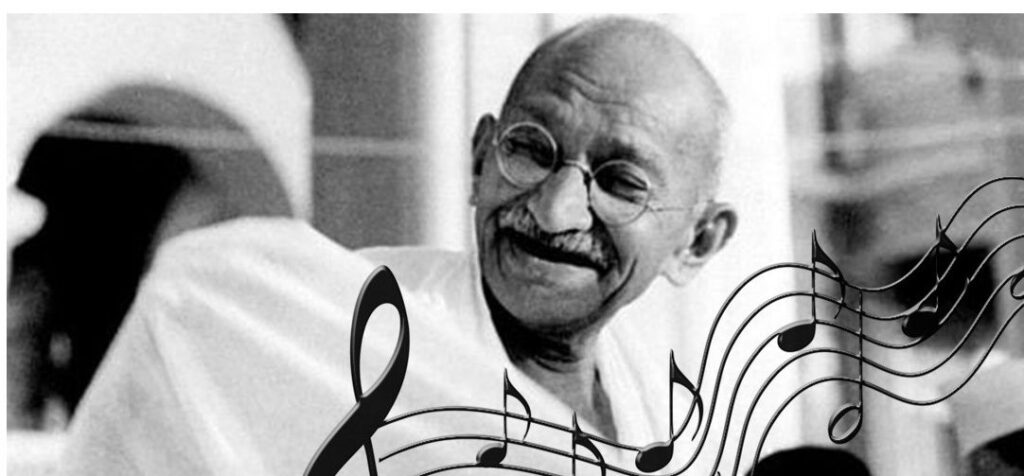

Gandhiji’s fondness for bhajans is legendary. Was it for the message of the lyrics or their musicality? Musings on Gandhi Jayanti 2020

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was leading a peasant revolt at Champaran of eastern India in 1917 when, down south of the subcontinent, an early teenager was grappling with an ancient musical instrument. K S Narayana Iyengar went on to became a master of the 21-string gottuvadyam and—a little over a decade later—reached the Mahatma’s ashram in Sabarmati to perform as a youngster.

The riverine hermitage in suburban Ahmedabad thus hosted a concert which brought to prominence a 15th-century devotional poem to national prominence. Such was the popularity Vaishnava Jana to earned across the common people of the 1930s and ’40s that it virtually functioned as a patriotic song to a whole generation and even for post-Independence India.

Khamaj is the raga to which the Gujarati poem by Narsinh Mehta resonated with the intended bhakti. The five-stanza work earned an added flavour, courtesy Iyengar (1903-59), much to the impression of Gandhi. Soon, its renditions lent a fresh spirit to freedom fighters, featuring in their meetings.

Vaishnava Jana to is arguably the bhajan that has strongest of Gandhian association. But a handful of other music pieces, too, did attract the Mahatma in his years busy with ending colonialism. Hari tuma haro being one. Again sourced from the Bhakti movement, the bhajan has been penned by mystic poet Mirabai (1498-1546), also from the western belt of India.

Coincidentally, the 11-line verse too, captured public imagination following its rendition by a classical musician from the peninsula. Carnatic vocalist M S Subbulakshmi sung it to the notes of Darbari Kanada—prominent in the Hindustani idiom despite the melody-type’s origins in the Deccan.

Least to be forgotten, Raghupati Raghava Raja Ram reverberated across the itinerary of the historic Dandi march. That was in 1930, when Gandhi led a civil disobedience demonstration from his ashram to the Arabian seashore in protest against a monopolistic salt tax. All down the 384 km of the 24-day walk, the volunteers chanted this excerpt from Sri Nama Ramayanam.

The lines are, primarily, by Lakshmanacharya, another Vaishnava devotee, of the 17th century. All the same, the 10-line extract was part-improvised to highlight a topical message: unity across faiths. For instance, Eshwar-Allah tero naam, Sabko sanmati de bhagavan calls for a harmonious Hindu-Muslim coexistence. The tune (for the original) was set (in raga Kafi) by Hindustani icon Vishnu Digambar Paluskar (1872-1931), even as some attribute the tweaked version to the Mahatma’s grandniece Manu Gandhi.

One can dub this as tampering with literature, but the exercise was in tune with Gandhi’s spirituality. So long as peace was the aim, the leader probably found no fault with tweaking a line or two.

To the Mahatma, devotional singing in public was no essential feature of the Hindu religion, says historian Lakshmi Subramanian, adding, Gandhi’s exposure to Christian singings in England and South Africa moulded his idea of a congregation. Back in India, he first heard Vande Mataram at Madras Assembly in 1915, and was impressed by the adjectives lauding Mother India (and not the use of the evocative Desh raga). “He did not appreciate the technicalities or profoundness of the classical traditions in India,” Subramanian is later quoted to have said in an interview.

Senior journalist Mrinal Pande notes Gandhi’s intertwining music in the form of prayers, chants and hymns was a “holistic nationalist effort to heal and fuse together a fractured nation”. Beyond a determined move against colonial assertion of western superiority, it sought to help India recover its pre-colonial secular identity, she says in an article in a leading Karnataka daily on September 30, 2018.

So, how much did music per se appeal to Gandhi as an art? Opinions differ.

A 1984 book titled Mahatma Gandhi: The Man and His Message reels back to the protagonist’s days in London as a barrister in his twenties. “He bought a violin and took lessons in music,” recalls the writer, Donn Byrne. “He even tried to how to dance, but he had no sense of rhythm and soon gave up his lessons.” Four decades later, Gandhi visited Santiniketan in Bengal. The arts in the campus did please the guest, but he later said the place served him with “an overdose of music and dance”.

Subramanian, in Singing Gandhi’s India: Music and Sonic Nationalism released early this year, notes Gandhi’s favourite bhajans enjoy “a vibrant afterlife” in independent India. Very true. In fact, on October 2, 2018, when the world celebrated the 150th Gandhi Jayanti, artistes from 124 countries came together to render Vaishnava Jana to.