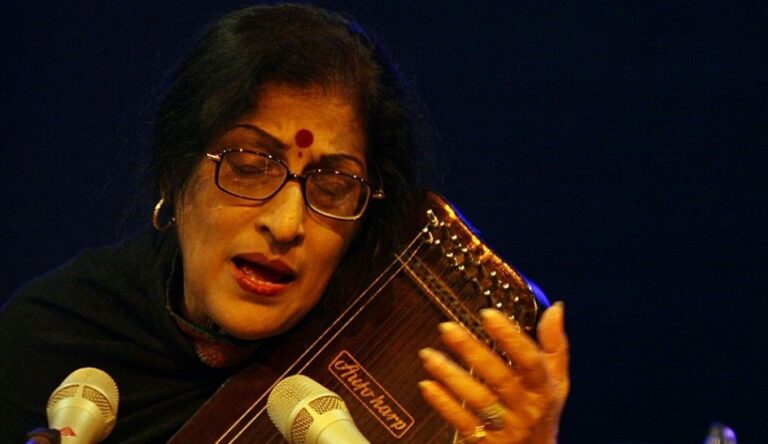

Padmavibhushan late Kishori Amonkar’s priceless and unparalleled contribution to Indian music will be remembered and cherished forever by music lovers, and artists alike. Today is her fourth remembrance day.

If MS Subbulakshmi is among the most revered female voices in Carnatic music, then Kishori Amonkar occupies the same position in Hindustani music. She was one of those very few artists, who not just added new dimensions to her own Jaipur Gharana through her renditions of ragas like Devgiri Bilawal, Shuddha Nat, Bihagda, Huseini Todi etc, but was equally successful in singing well-known ragas like Yaman, Bhoop, Bageshri, Bihag and so on. The bhajans and other lighter songs rendered by her, also show her attitude to constantly innovate.

Jaipur gharana is generally noted for singing complex ragas, and being extremely structured. While teaching a khayal or a bandish, the gurus of this gharana would emphasise on each letter of every word to be falling on a specific part of a matra. Even during alaps, Jaipur gharana musicians do not sing offbeat. In other words their alaps are also totally bound by laya.

This extremely structural discipline resulted in less emotive appeal and more focus on grammar and acrobatics. Amonkar changed all this and brought more emotive appeal in her renditions. She says, “I often wondered if someone sings ghazals or bhavageets, people love it, but why so few people come to classical concerts? Isn’t classical music related to human feelings?”

The word classical is defined in the dictionary as, there is nothing beyond this. If raga music is referred to as being classical, then it should be able to express all human emotions. To bring emotive appeal to her music Amonkar studied the science of rasa, and would often introspect as to whether a particular phrase or style of rendition expresses the bhava of the raga.

Advaita philosophy in music

Amonkar always believed that the raga rendition should only focus on expressing the raga bhava through notes. It should be beyond a person’s individual style/temperament, his command on acrobatics etc. “Once my mother asked me whether I am going to present the raga as I have understood it, or the raga as it actually is. This made me focus on understanding the many dimensions of the raga. I believe that our advaita philosophy should be applicable to my music. In other words, I, and the Raga which I render should be totally merged.

I have often experienced that, if I forget myself while rendering a raga, the raga shows it’s full aura. My aim is that people need not remember me, but remember my renditions. People should not say that, Kishori sang Bageshri beautIfully, but instead should say that the Bageshri, that Kishori sang, was beautiful. Kishori is mortal, but the raga is immortal, and Kishori should be only the medium to express the Raga.” she said.

According to Amonkar, the ultimate purpose of Indian music is to attain Moksha. That is why things like pranayam, dhyana etc, are deeply related to Indian music. “My mother would tell me to sing only Sa, 108 times every day and then would ask me, whether I was able to see and feel the note. If I said no, she would make me do it, until I see it.” she says. “Our Rishis like Bharata have written that various notes like Sa, Re, Ga, Ma etc. express different rasas.

Unless we reach that level of sadhana, we do not have any right to refute this. It has been mentioned that, Gandhar expresses Karuna Rasa. To find out whether this is true, we should sing that note thousands of times. I myself have experienced that, if I sing the note Ga with a neutral mind, it invokes within me, the feelings of love and compassion. Similarly, if I sing the note Pa with a neutral mind, it invokes the creative power within me, as Pa expresses Shringar Rasa”. She believed that every musician should study the ‘Rasa Siddhanta’, explained in the books like Natyashastra, Sahitya Shastra etc, in depth, so that he can express various emotions through notes.

Extensive study of shrutis

Amonkar also studied the science of various shrutis in music and would always focus on hitting not just the correct note, but it’s correct shruti for that raga. She said, “Since our Indian music is totally related to nature, our notes follow geometrical progression in terms of the distance between them. The shruti of each note in a raga depends on the presence of other notes in that raga. Many so-called pandits have written that the shrutis of Sa and Pa do not change, but it is totally wrong.

Just like the love between a parent and child, a brother and sister, or two lovers is totally different from each other, the shruti of a note Re is different for ragas like Bhoop, Hamsadhwani, Shudhakalyan etc. Each Re expresses different emotions. According to me, the study of a raga is not just the study of its aroha, avaroha, bandish etc. but the knowledge of Shrutis to be used in the raga. It is said that there are 22 shrutis, but there are many shrutis in music. Some come through Meend, some through Gamakas, and some come plainly. The duty of an artist is to find out the correct shrutis for a raga, and try and apply the same in his rendition.”

Rebelling genius

To bring more raga bhava, Amonkar used some non-traditional note combinations, as she always focused on bringing more beauty in her rendition than singing only the basic structure of the raga. One can experience this, while listening to her renditions of ragas like Bageshri, Yaman, Jaunpuri, Miya Malhar, Shuddha Kalyan etc. She said, “Once I asked my mother about the chalan of a raga. She asked me whether I wanted the chalan of the raga, or the raga itself. Then I realized that the chalan is only the gate-way to the raga.

For example if you sing the important phrases of Nand for around 500 times, slowly you start to see the region beyond that, and the raga starts to show its many dimensions.” While talking about Bageshri she once said, “We are told that the note Pa should be used in small proportions. I found that people use pa in only a few phrases like Ma Pa Dha Ga. I thought of singing some other phrases with pa in small proportion, and many different phrases came to me.”

Impact of light music

Kishori Amonkar often paid great importance towards pronouncing the words of a khayal/bandish. She was often troubled by the words of compositions, as according to her, the words of the composition should be in line with the raga bhava. According to her, a raga like Bilaskhani Todi is not suitable for compositions like Ni Ki Ghungariya, or a raga like Darbari Kanada is not suitable for a composition like Jhana Jhanakawa Hamare Bichuwa etc. Even while singing the khayal/bandish she would try to bring the Bhava of those words in her music. She said, “If I sing a bandish like Kaise Din bite (Raga Bhimpalas), one should not sing too many Taans with Gamakas. While singing the Khayal like Baje Baje Damru (Raga Gunakali) one should focus on the Meends in that song which express the correct emotion of the words.”

Creation of new ragas and bandishes

Amonkar created many Jod Ragas like Lalat Vibhas, Adana Malhar, Anand Malhar (yaman and malhar), Nandshri (nand and bhinnashadja) etc. Her bandish like Sahelare (Raga Bhoop) is extremely well known. Many times her bandishes would have only Asthais. For example, Jhanja Ranga Sanga Baje (Bhoop). Another of her famous compositions is Ganapata Vighana Haran Gajanan (Hamsadhwani).

Amonkar sang for a movie Geet Gaya Pattharon ne. She also sang many Marathi Bhavageets like He Shyam Sundara Rajasa etc. When Prime minister Indira Gandhi died, she sang Ovis from Dnyaneshwari on Doordarshan. Her bhajans like Mharo Pranam, bolawa vitthala, Awgha Rang Ek Zala etc are very popular.

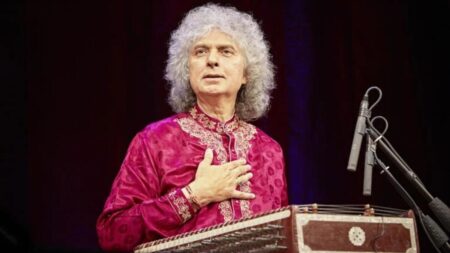

Amonkar performed Jugalbandi concerts with the Carnatic maestro Dr. M.Balamurali Krishna, and flute maestro Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasiya. She also sang for a French opera.

Amonkar also sang many Ghazals and other compositions on radio, but refrained from singing them in concerts. She also composed many ghazals in Marathi, Hindi and Kannada, which are now being rendered by her disciples.