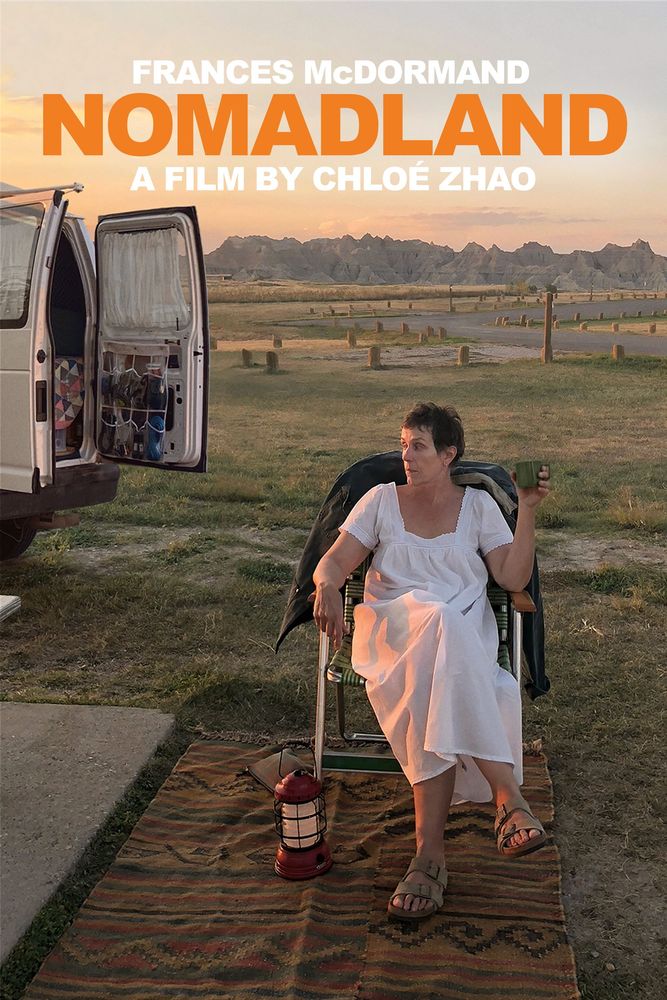

The Oscar-winning American film Nomadland, directed by Chloé Zhao and starring Frances McDormand, is a clinical examination of the chinks in American capitalist society. It is the Grapes of Wrath of the gig economy era.

No, I’m not homeless. I’m houseless. Not the same thing, right?” states Fern (Frances McDormand) in Nomadland. The scene, like many such moments in the Oscar-winning American film directed by Chinese filmmaker Chloé Zhao, becomes an open critique of the existing social systems in America and beyond. Based on the 2017 book, Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century, by journalist and academic Jessica Bruder, the independent film offers students of American capitalism and the society it powers enough material, much like The Grapes of Wrath exposed to the rest of the world the vagaries of Great Depression on the American society, especially its working class.

For the sheer clarity and conviction with which it looks at the lives of a group of Nomads, who are basically individuals abandoned by a society that does not believe in offering succour to those who don’t ‘earn’ or are not in a position to find ‘proper’ employment to support their socioeconomic needs. Take Fern, the protagonist of the movie. She lost her job in 2011, when a plant owned by US Gypsum in Empire, Nevada, shut operations.

Empire was a company town. For starters, a company town is an area that’s controlled by a giant company or corporate since the people living there are its employees and their families. Most of the needs of the populace are met by the corporate. But when the fortunes of the corporate start diminishing, the workers are left to fend for themselves. Most people relocate to other geographies in search of jobs and a better life. Some, like Fern in Nomadland, hit the road, literally, doing odd jobs as they travel to nowhere.

The nowhere people

Fern wasn’t a nowhere person. In Empire, she had a husband, who was a worker at the US Gypsum plant. But when he dies, Fern was left with no options but to sell her stuff and buy a van and travel across the American West, looking for work. It is this journey that journalist Bruder had written about and Zhao and team depicted with brutal honesty in Nomadland. Fern’s journey is not linear. She crisscrosses the region, running into a bouquet of nomads who share a similar plight and in that process learns a lot about herself, the world around her and an apathetic, social Darwinist system that leaves no room for remorse or rapprochement.

Fern soon joins the great American army of temp workers. During the winter, she takes up a seasonal job at an Amazon fulfilment centre and travels to warmer and more conducive locales once that job’s finished. For millions of people like Fern who’re employed in the gig economy (mostly temporary, flexi jobs that offer no social security cover or benefits), secure employment becomes a chimera. More than the absence of a place to stay, it is the fact that they might never find proper employment, that makes them the ‘nomads’.

On that cue, Nomandland is the story of the unmaking of the American working class. In his seminal work, The Making of the English Working Class, EP Thompson writes that class is not a ‘structure’, nor a ‘category’, but “something which in fact happens (and can be shown to have happened) in human relationships”. Fern’s life, journey and encounters stand testimony to this. She continues to be a member of the working class in a technical sense of the term, but she is far removed from the perks and protection that a typical member of the working class used to enjoy. The world and her relationship with it have changed beyond recognition for her. She is in a transitory stage. In this purgatory existence, she is neither a ghost nor a living being; she is not a stat, nor a data point. She exists because she wants to. Like the other ‘nomads’.

A deadly cocktail

Evidently, Nomadland offers a disturbing glimpse into the world of the left behind. When Empire was disbanded as a company town, and when the Zip Code was scrapped off history, not many bothered about those that were left behind. The workers and their families were nobody’s business. One can find an eerie parallel here. As Judith Stein observes in Pivotal Decade: How the United States Traded Factories for Finance in the Seventies, it was the era of postwar liberalism, brought in by the New Deal, that heralded the happy age of high wages and regulated capital in America. Clearly, the period powered economic growth and greater income equality. But when the American regime “traded” factors for finance in the 1970s, apocalypse followed, mainly for the working class.

Ever since workers in America started losing all their rights and privileges one by one. By the 2000s, when finance capital started showing its Frankenstein fangs, the working class was left in the lurch to bleed and die in their dingy alleys. The era of New Manufacturing and the rise and rise of the service economy did ensure the working class was robbed of their basic rights, forcing them to flee. Even though the financial meltdown of 2008-09, powered by the meltdown of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, ushered in an era of soul searching for American capitalism, nothing much was done to bring the focus back on the working class.

The advent and rise of the gig economy, powered by predatory, discriminative technologies and the growth in income inequality, aggravated the situation for the working class further. Nomadland is the story of what’s happened later. It is also the story of what’s going to happen to the remaining chunks of the working class if urgent policy changes were not introduced to address the rights of the ‘left behind’. The film and the book hold a mirror at the American society and what it sees on the mirror is not at all a rosy reflection.

It is a broken portrait. “There’s a crack in everything. That is how the light gets in,” said Leonard Cohen. In fact, the book Nomadland begins with this quote. Interestingly, the book has another quote that can be read as a manifesto of sorts: “The capitalists don’t want anyone living off their economic grid.” — Anonymous Commenter, Azdailysun.com. As nomads such as Fern, Linda May or Swankie live off their simple but uncertain existence, away from the madding crowds and off the economic grid of capitalism, it’s interesting to see how a filmmaker from China, an economic powerhouse that to some offers an alternative to American capitalism and its tributaries, documents the life of the leftovers of one of the most powerful economic systems that have shaped the world as we know it today.