In her ‘screen-prints’, Delhi-based painter and printmaker Shivangi Ladha maps myriad moods of the human body and morphs them into complex metaphors.

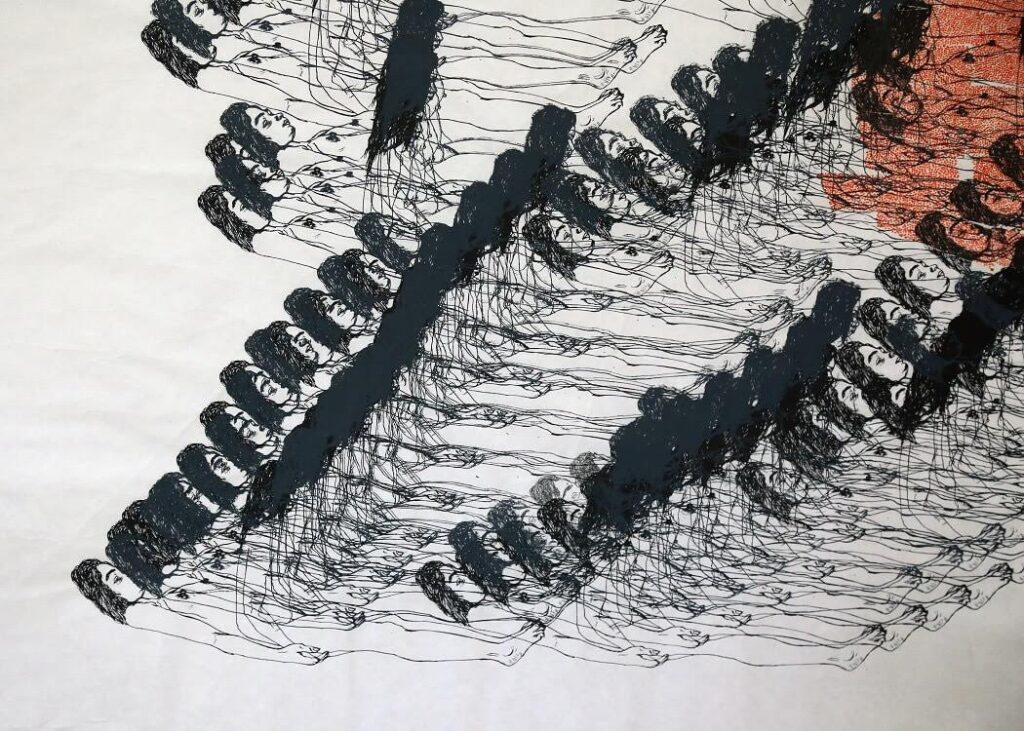

Printing through the screen constantly takes new meanings in the practice of visual artist Shivangi Ladha. One of Ladha’s earliest screen print series, Self Portrait, shows a single body repeated over and over itself into acts of sleeping-waking up. In every subsequent registration, the printed body displaces and decentres itself from its earlier position.

Looping into the above acts signifying inaction and action, the body appears to be suspended in a hallucinatory dream alluding to escape itself. A frantic performance of layering takes place in the following frames wherein these bodies riot and render the canvas opaque. The screened selves camouflage and contest with each other, transforming the body itself into a screen.

Screening here is not merely the artistic technique through which the body makes itself apparent in Ladha’s works. Rather, the screen could be a metaphor for the body – the interface through which the world outside gets perceived and performed. In screen printing, the silkscreen hides the figurative body only to make it appear again to the printer’s act.

In the countless acts of iterative printing, the artist attempts answers to her feeling of placelessness and unbelonging during her time spent in a distant land.

She says, “the act of repetition changes oneself from within rather than the thing outside”. In this repetitious performance thus, Ladha meditates upon herself, her displacement, identification and orientation with the world at large. It is a means through which she comes to terms with the existential questions engendered within her material presence while being away from home.

Fleshing it out

If the body is the primary physical interface through which the self comes to interact with the external world, then its close observation becomes imperative in its artistic practice.

At this juncture, Ladha raises the problem of the anthropometric gaze in her print titled Body in Space. In its specific corporeal construct, the human eyes do not reveal to us the physical entirety of our body at once.

Rather, the gaze makes us focus on a single part — the body’s contours and construct in the grain and texture of the flesh. These microscopic details of the flesh are enlarged as fine lines printed onto the surface of suede leather. In doing so, the artist collapses different scales of autopsied skins onto each other in their representational reality. Both dissected and detached from their original sources, the juxtaposition of the human skin on suede leather reminds us of our masked existence merely held together in bodily flesh.

It is such preoccupations that led the artist naturally towards her Acid Attack Survivor series. Questions of material, body and flesh took a new rendering in her practice on her unplanned encounter with the employed acid attack survivors at a café in Agra, India. Ladha was deeply moved when she met these survivors in person for the first time and found herself delving deeper into their stories.

Although acid attacks are reported in many countries across the world, their numbers are particularly high in South Asia. The violent assaults via acid attacks not just leave the victims with permanent physical damage, but also cause tremendous psychological damage. Disfiguration caused via such vitriolic attacks often is irreparable despite repeated plastic surgeries.

Acquired by The British Museum, London.

Survival stories

To respond to the above realisation through her print practice, Ladha decided to adopt the process of etching to record and embed the victims’ experience in her artistic process.

As one may note, etching is a method of making prints from a metal plate into which the design has been incised by acid. The ruptured faces of the survivors are freshly created onto metal plates through an acid bath to be eventually printed onto the paper.

While on the one hand, the aberration on the metal surface is analogous to the blemishing of human flesh, it is also the stage one must arrive at to realise a work of art.

In this vein, Ladha confirms, “Rather than a destructive agent, I use acid to create and celebrate the acid victims’ very struggles of everyday survival.” The resultant works are a series of eight unique prints that hold the gaze of the viewers to faces that have lost their original bodily outlines.

Unique Print; Acquired by The British Museum, London

The etched lines in the portraits of the acid attack survivors de-map the conventional contours of the body and emphasize its morphing into new geography. These distortions challenge the viewer to rethink the normalised gestural language of the body. The horror and shock endured by the victims are transposed upon the onlooker towards interrogating the limits of facial expression.

Further, the artist layers parts of these etched faces with coloured registrations in a manner of turning the tissues inside out. These red patches allude to plasmatic cells that seek their redefinition within the etched facial geographies.

In tensioning these values of the inherited and the acquired, natural and morphed, silence and violence, Ladha coaxes a quiet neuroaesthetics of alienation.

Uncertain existences

Issues of body and gender recur in Ladha’s practice rather subconsciously. These underlying preoccupations get foregrounded yet again in her Oneness series inspired by a socio-environmental experiment practised since 2006 in the Piplantri village of Rajasthan.

In the memory of the village head’s daughter who passed away due to illness, the villagers of Piplantri plant 111 trees every time a girl child is born. As she moved around the village, she found the women preparing the designated areas in the village for the next plantation. “I imagined the entire village to be green,” exclaimed the artist.

The above environmental approach may also be to regenerate the original landscapes around the village lost to excessive mining. Ladha maps this historical transformation of the village from an arid desert into an oasis of a variety of trees through the method of monoprinting.

Unlike other techniques of printmaking which allow multiple originals, in monoprint, the image can be transferred only once. This precarity invites the viewers to think deeply about erasure – of the girl child and the forest – alarming us to the regenerative uncertainty of our social and environmental futures.

In Ladha’s rendering of Piplantri, the forest and girl children create and care for one another. The chiaroscuro of the foliage reveals as well as covers their naked bodies. The vulnerability of their survival and existence is expressed in the one-time act of transferring the image onto the paper.

“The results of printing are always uncertain – one doesn’t know which parts will appear or disappear…”, Ladha contemplates. It is in these acts of making that Ladha locates the meaning of her artworks through techniques of screen printing. The endeavour in every subsequent iteration of her practice is to unveil the screened selves, one at a time.

Shivangi Ladha: A profile

Shivangi Ladha graduated from Royal College of Art London, in 2016 with a specialization in MA Printmaking. Before this, she pursued MFA in Fine art from Wimbledon College of Art, London and a BFA In Painting from College of Art, Delhi University.

She has undertaken many residencies internationally in the UK, Spain, Canada and the USA and consistently exhibited works that have entered prestigious collections such as the V&A Museum, the British Museum, London; Mead Museum, Massachusetts; the Reliance Foundation, Mumbai; Anant Art Gallery, Delhi; and many private collections. In 2022, she was nominated for the Queen Sonja Print Award, a major international print prize.

She is also receipt of the Taf Emerging Artist South Asia Award 2021; New Prints Artist Development Award, International Print Centre New York (IPCNY), USA 2018; Anthony Dawson Young Printmaker Award, (Royal Society of Painters – Printmakers RE) 2017 and Jerwood Drawing Prize 2014, UK to name a few. She has also created a space for other artists to show and make work by initiating India Printmaker House, a platform to facilitate workshops, exhibitions, prizes and residencies. She has taught widely in Delhi, across all ages and in different contexts.

Thus spake Ram Dass

After her trip to Piplantri village near Udaipur, Ladha accidentally met Aditi, an artist who noticed her engagements with stories of the village on social media and invited Ladha to her studio. As Ladha shared her experience of the forest and trees with her, Aditi visually imagined the structure of a book in her mind.

It is here that they decided to collaborate and create a book. Ladha decided to use the aquatint technique, a variant of etching that produces areas of tone rather than lines to create a fountain of flowers spurting out from the nodal point of the book.

The printed pleats and petals of the flowers in different degrees of shades invite new readings into their folded forms that also play with the folds of the book. All of these emerge as well as converge into the delicate fold of the yoni – the womb at the centre that produces and reproduces the world. Seen thus, the book soon appears as a mysterious tree of secret knowledge that unfolds into the various shades and forms of nature.

Ladha sums up the above project as a part of the Becoming Trees series in recalling the words of appreciation and acceptance by spiritual teacher Ram Dass through which she validates and seeks her own meanings in turning people into trees.

Ram Dass says:

“When you go out into the woods, and you look at trees, you see all these different trees. And some of them are bent, and some of them are straight, and some of them are evergreens, and some of them are whatever. And you look at the tree and you allow it. You see why it is the way it is. You sort of understood that it didn’t get enough light, and so it turned that way. And you don’t get all emotional about it. You just allow it. You appreciate the tree.

The minute you get near humans, you lose all that. And you are constantly saying ‘You are too this, or I’m too this.’ That judgment mind comes in. And so I practise turning people into trees. Which means appreciating them just the way they are.”