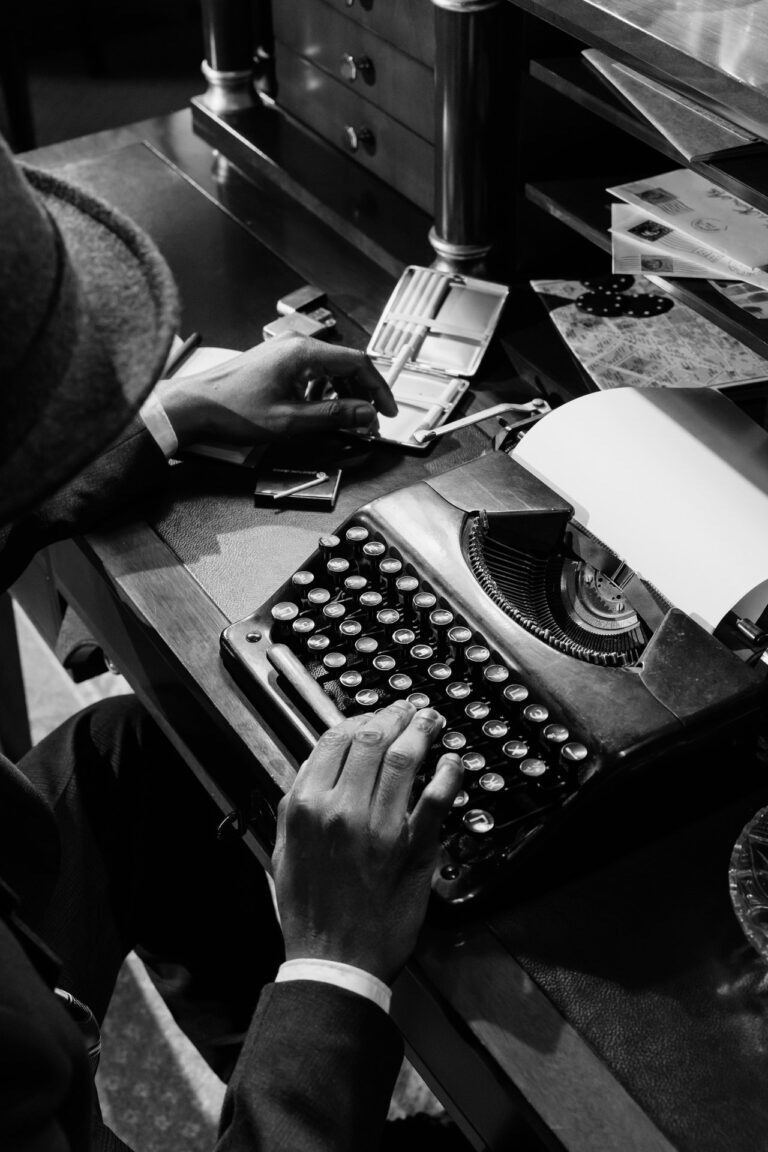

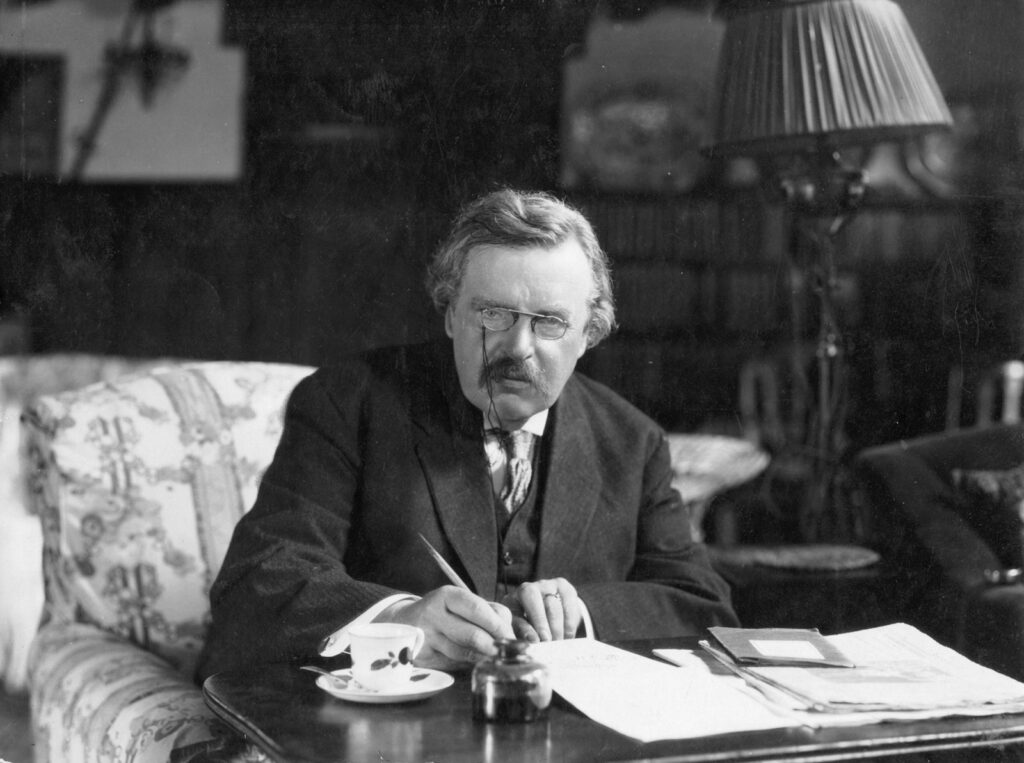

A true artist of the written word, G.K. Chesterton was much more than a mystery writer.

While I was studying in the 7th Standard (B Division) at Loyola School in Thiruvananthapuram, my class teacher was suddenly taken ill and had to take leave for three days. This news should have made the motley crew of 30 odd ruffians and hooligans masquerading as 12-year-olds (except for one saintly bespectacled lad, whose name modesty forbids me from revealing here) sad and full of sympathy on hearing about their teacher’s affliction.

Unfortunately, as is often the case, this was not the reaction of these unkempt and barbaric young gentlemen (I use the term gentlemen in its loosest possible sense). The reactions ranged from indifference to ecstasy, mostly the latter. Plans began to be made about how to spend the vacant periods playing book cricket, organizing paper ball fights or discussing India’s dismal cricket tour of England, now known to all cricket lovers as the nadir of Indian cricket, ‘The Summer of ‘42’.

Entering, a mysterious man

The sudden appearance of the Vice-Principal brought a sudden end to these discussions. He was accompanied by a slim youngish man of medium height who we had seen around the school and knew was a teacher. However, as he was not teaching us any subject, none of us knew anything more about him. The Vice Principal glared suspiciously at the suddenly angelic-looking faces demurely gazing at him.

This, he said, gesturing to the diffident looking young man, is Mr Chittoor. Since your class teacher will not be available for three days he will take classes in her stead. I am sure you will all provide him with utmost cooperation. I don’t need to add that any report of unruly behaviour will be dealt with with utmost strictness and the perpetrator will find it painful in the end. He did not have to specify further, a few of the usual suspects were already surreptitiously rubbing their ends because of the mental picture his words evoked.

With a final basilisk like stare, the Vice Principal whisked out. Mr Chittor timidly glanced around the class. It was apparent that he was intimidated by the scowling, baleful faces turned towards him (except for one radiant, angelic bespectacled face, of course). He hemmed and hawed for a bit and then finally blurted out that he did not see any point in taking classes for three days as his manner and method of teaching would be different from our class teacher’s and this may make it difficult for our already obtuse minds to grasp anything.

Instead, he proposed, he would tell us a story in each period to while away the time. The boys glanced at each other. While not as enjoyable as book cricket, paper ball fights or throwing ink at each other, this seemed vastly more enjoyable than having to study boring subjects that didn’t interest anyone at all, especially the aforementioned angelic boy. There was a chorus of approval.

Introducing Chesterton

M. Chittoor cleared his throat and began his story. It was a detective story called ‘The Blue Cross’ but it did not feature a hawk-eyed, athletic detective proficient in jujitsu who could mop up battalions of villains without breaking a sweat. The detective in this story was a small, dumpy Roman Catholic priest in a shapeless cassock and armed not with a Winchester or Colt.45 but with a large, ungainly umbrella.

While the fact that the hero of this particular story was a priest left the boys singularly unenthused, fed up as we were of priests who we encountered every day in school, the mutinous muttering in the class gradually died away as the boys fell under the spell of the story. Mr Chittoor was a raconteur, undoubtedly descended from those legendary storytellers of old whose tales, passed from generation to generation, were the basis of history and culture before the written word.

He had the gift of making his listeners feel the drama, of evoking the atmosphere and making us hang breathless on his words until the spellbinding conclusion when the tangled skein of mystery was unravelled. I was mesmerized by the story and its protagonist. This was a new kind of hero, very different from the Lone Rangers, Saints, Doc Savages and Suddens who I idolized. I waited impatiently for the next day and Mr Chittor did not disappoint. This time the story was called ‘The Secret Garden’ and it was as good as its predecessor.

On the third day, he told us the story of ‘The Queer Feet’. After that, he faded from our lives as diffidently as he had entered it. The impression he left on one young mind, at least, was huge.

I immediately rushed to the British Council the next Saturday and requested the Chief Librarian, my hero and a repository of information on all things bibliographic, to get me books about a priest known as ‘Father Brown’. He did not fail me, informing me that the books were written by an author called G.K. Chesterton guided me to the appropriate shelf where I found two of the books, The Innocence of Father Brown and The Wisdom of Father Brown.

I had already heard of Chesterton having read his essay On Running After One’s Hat in a book my father had in his collection called Essays of Yesterday and Today. I remembered that the essay was funny and written in wonderfully stylized prose, most of which had gone over my head at the time.

Priest of a different kind

These Father Brown books though were a horse of a different colour. Atmospheric and intricately plotted, they held one’s attention from the first sentence to the last and on every occasion defeated my efforts to guess who the criminal was, or how the crime was committed.

Father Brown though mild and self-effacing, had a razor-sharp mind and years of ministering to people and listening to hair raising confessions had given him an insight into the ‘nature of evil’ and he solves the most complex crimes with his intuition and understanding of human nature.

In this, he was similar to another mild and self-effacing detective who would become famous in the coming years for her knowledge of human nature culled from experiences in a little English village, Agatha Christie’s redoubtable Miss. Marple. I would put the Father Brown stories on par with the Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle and his prose is much more engaging. Soon I had borrowed every book by Chesterton I could find including all the Father Brown books (totalling 53 short stories), The Club of Queer Trades, The Paradoxes of Mister Pond, The Man Who Knew too Much and The Man Who Was Thursday, among others.

A towering figure

Most of these were mystery story collections written in Chesterton’s delicious language; he was a true artist of the written word. He was much more than a mystery writer though.

G.K. Chesterton wrote extensively on philosophy, theology, poetry, art criticism and politics and was a fabulous essayist and playwright. He was one of the first public figures in England to oppose Hitler during the nascent days of Nazism when Hitler had many admirers in England, especially among the right-wing conservatives. He was a close friend of writers Hilaire Belloc, E.C. Bentley and George Bernard Shaw.

A huge figure of a man, well over six feet tall and well covered (to put it delicately as Obelix in the Asterix comics would have it), P.G. Wodehouse once described a loud cacophony as ‘…a sound like G.K. Chesterton falling on a sheet of tin’. Any lover of detective stories, well-written essays, poetry, plays or anyone who has been seduced by the beauty of the English language would do well to seek Chesterton out. You will not be disappointed.