The year was 1914. American Vogue editor Woolman Chase returned to New York empty handed from France. And the magazine pages were blank. Chase had an idea.

Growth of Runway Fashion

The American edition progressed more glamorously through the war since no battles were fought on their soil. Theirs was a different challenge. In August 1914 the Germans declared war on France, just as Woolman Chase arrived safely back home to New York. She was returning from a couple of months visiting designers in Europe, but she was empty-handed.

The war had caught Paris at a bad time for fashion. It was right before the autumn collections; always a citywide production involving millions of francs, thousands of workers and meticulously orchestrated theatrics. A buyer for an American department store later described his experience of being trapped in the capital during mobilisation and he keenly remembered running around the ateliers trying to score some dress models to haul back home.

Many of the couturiers hadn’t completed their designs and while the American buyer witnessed many tender scenes of farewell – including famed designer Paul Poiret in a blue-and-red infantry uniform, surrounded by his adoring female staff – he found few clothes for sale. Part of the problem was that most couturiers were male and were preparing to join the army rather than finishing gowns. Female couturiers largely went ahead with their collections, but they were thin on the ground. For Woolman Chase this was inconvenient news. She had no way of knowing that after the first few months France’s haute couture industry would resume business as usual. All she heard from her foreign correspondent in Paris was that a sense of mourning and hopelessness was seeping through the country like a sickness.

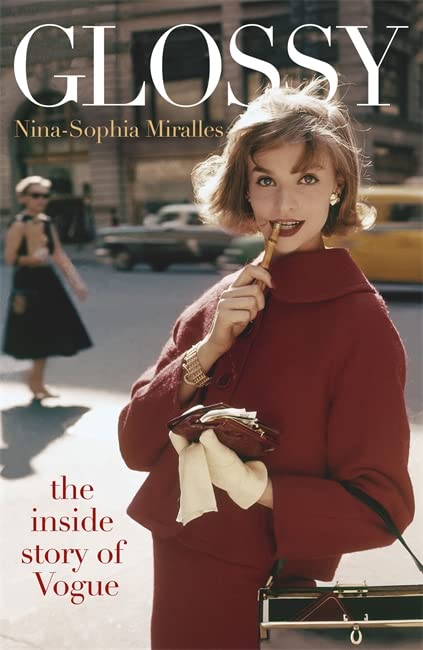

By Nina-Sophia Miralles; 330 pages; Rs 899; Quercus

Publishing date: 18 March 2021

How on earth was she supposed to fill the pages of her magazine without French fashion? Paris was the centre of style, the one and only authority on clothes. Mulling this problem over on the bus to work, she suddenly remembered the Vogue dolls which had been used as a publicity stunt back in Turnure’s time.

These figurines had been kitted out in miniature versions of dresses by New York designers and exhibited to a curious public. Woolman Chase had one of her many lightning moments. By the time she got to the office she had a clear idea in her mind which, marching straight to Nast’s office, she pitched to him. If they had no clothes to feature in Vogue they would have an empty publication. Since there was nothing coming in from Paris why not get a group of New York designers to create original pieces, then show them off to society ladies at a public event? The garments could be displayed on other women selected specially and they could walk, one after the other, in front of the audience.

The ‘show’ could even be sold as a charity benefit with profits going to help the war effort in France. Woolman Chase would have enough fashion designs to print in Vogue, solving her editorial problem; American design could be introduced to the world, since up until then France had a monopoly on couture; and they could raise money to support their suffering friends in Europe. Still, Condé Nast was suspicious. He struggled to see the appeal of watching people walk while wearing clothes. Woolman Chase later explained: ‘Now that fashion shows have become a way of life, it is difficult to visualize that dark age when fashion shows didn’t exist.’

It does seem impossible to visualise now, but Woolman Chase had to really fight to convince anyone. Most importantly, she had to persuade someone worthy to act as patroness or Nast wouldn’t let her go ahead. New York society was as closed as ever, its door sealed shut against any new ideas, the gaze of the glacial grandes dames who presided over the city ready to freeze out any upstarts. They also refused to be involved with anything commercial. Woolman Chase was determined to push the charity angle, but the involvement of Vogue might be enough to alienate since publishing was a business and business was beneath them.

In her mission to get her project off the ground Woolman Chase determined to go right to the top and approach the most illustrious and imposing madam of them all. Once that had been Mrs Astor. Now it was Mrs Stuyvesant Fish. Known as a ‘fun-maker’, fun she does not look. In photographs Mrs Fish’s slab-like bosom is draped in finery, her wide frame squeezed into a frightening corset and her expression would have made Queen Victoria look downright jolly. To get to the assigned meeting on time Woolman Chase had to catch a train before sunrise, making her way to Mrs Fish’s mansion with trepidation.

Once there, Mrs Fish’s secretary came down and told Woolman Chase that Mrs Fish wouldn’t see her after all. Unsure what to do next, Woolman Chase lingered in polite conversation with the secretary, who, it turned out, had a son who liked to draw. Wouldn’t Mrs Woolman Chase as editor of Vogue be able to look at his work and see if it was any good? Graciously agreeing, Woolman Chase commented what a shame it was that nothing could be done to persuade Mrs Fish to hear her out. The secretary took the hint – and went back upstairs to plead with the formidable woman to give the editor a chance.

Once in front of Mrs Fish, Woolman Chase coaxed her round. The net result was a brimming list of patronesses that was labelled a ‘stunner’. With Mrs Fish’s help, some of the juiciest names in New York stepped up to the plate, including the likes of Mrs Vincent Astor, Mrs William K. Vanderbilt Jr, Mrs Harry Payne Whitney and Mrs Ogden L. Mills. At the sight of this impressive roll call, Condé Nast completely buckled.

With the green light from Nast, Woolman Chase busied herself with other details. She christened the event a ‘Fashion Fête’; chose the Committee of Mercy which helped widows and orphans of allied countries as the recipient of the profits; booked the ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton; and hand-picked seven patronesses to act as judges, although this was just a cover.

Woolman Chase realised that any dressmakers, boutique owners or department store representatives who paid for advertising in Vogue but were not picked to exhibit at the fête might be offended and pull their ads. She didn’t want to compromise on the quality of the clothes shown so, craftily, she told each client that she would love to show their pieces, but sadly the ‘judges’ picked out the designs and she had no sway over them.

She performed yet another service to fashion by training mannequins, teaching the carefully selected beauties to strut and pivot professionally. Her goal was to get them to walk in a way that would convince onlookers this was a real art, rather than the random machinations of an ambitious editor. The catwalk strut might well have been popularised here and the Fashion Fête had big consequences for modelling, raising awareness of the profession across the United States.

The evening was a resounding success, starting with a dinner, after which all the smart ladies went up the curving staircase to take their seats for the show. At the time it was so unusual for these mighty New York families to mingle with the common folk that the attending socialites considered themselves quite intrepid for spending a night with models and dressmakers.

A number of high-end brands we still know today, such as Bergdorf Goodman, were launched on to the fashion scene that night. The fête took up a good eleven pages in the Vogue issue of 1 December 1914. Woolman Chase’s fear of empty pages was avoided.

‘Excerpted with permission, from Glossy: The Inside Story of Vogue by Nina-Sophia Miralles, published by Quercus and Hachette India’

Write to us at [email protected]