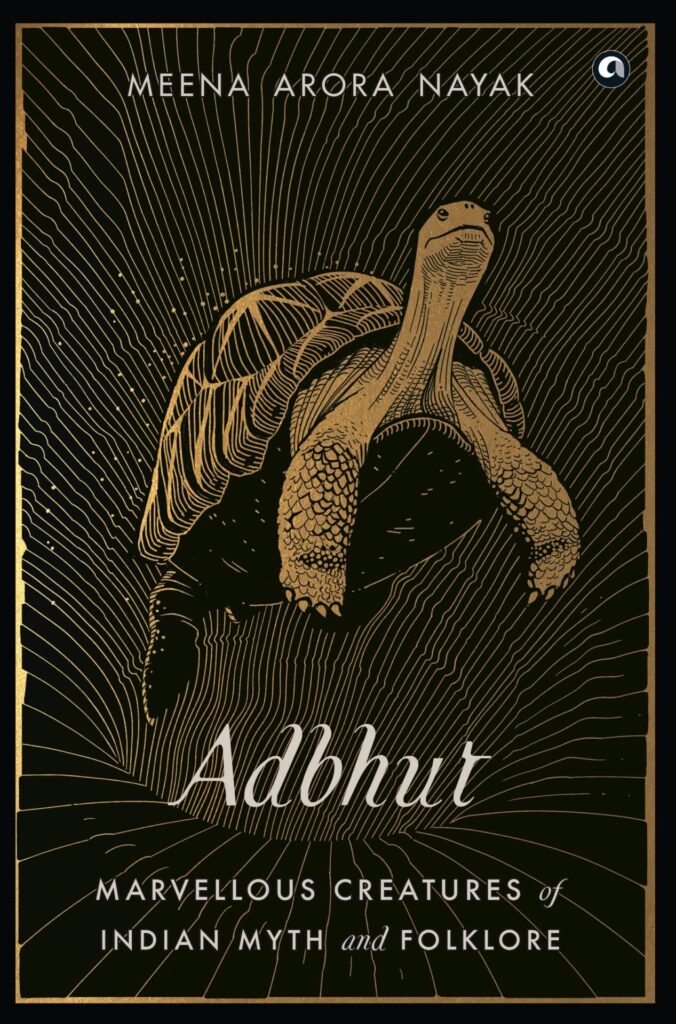

In Adbhut, author Meena Arora Nayak brings to life the marvellous creatures in Indian mythology and folklore. Here she writes about the creatures of the water – Kurma and Timingila – from the Mahabharata

Kurma The World Tortoise

Kurma the tortoise existed even before Prajapati, the primogenitor of the world. In the beginning, Prajapati alone came into existence on a lotus leaf. When he felt desire in his mind, he said, ‘Let me bring forth the universe.’ And to do so, he performed austere penances, after which, he shook his body. From his flesh, red rays emitted; from his nails and hair, clans of rishis leapt out; and from his bodily fluids, strange, demonic beings formed. Just then, he saw a tortoise moving in the middle of the water, and he said to him, ‘You, too, have come into being from my skin and flesh.’

‘No,’ the tortoise replied. ‘I have been here before you. I am Purusha, the primordial man of a thousand heads, thousand eyes, thousand feet.’

Prajapati realized that the tortoise was, indeed, born before him, and he said, ‘All that is svayambhu—self-born—is Brahmana, the ultimate reality.

In the Shatapatha Brahmana, Kurma is Prajapati himself, who brings forth all creatures. Whatever he created, he himself made, and because he made it, he is called Kurma. Rishi Kashyapa, the Saptarishi, one of seven progenitors of the world, is also kachhapa—Kurma; from him came the Adityas, who are the solar gods, and the daityas and danavas, who are forces of darkness, and the mortals, who are his progeny.

Kurma is also Vishnu. When the gods needed to churn the Great Ocean to acquire soma, the elixir of immortality, they begged Vishnu for help. Vishnu took the avatar of Kurma and became the churning base to bear the weight of the grinding, swirling churning stick of Mount Mandar, which rises eleven thousand yojanas upwards and plunges eleven thousand yojanas downwards.

According to Vaastu Shastra, this kurmashila, the tortoise foundation, is stability. That is why at the beginning of Vaastu puja a Kurma image is placed in a lotus that sits on a water pot. A metal tortoise is also buried at the base when the foundation of a house is laid. Temple pillars, too, rest on the backs of tortoise sculptures.

Kurma’s lower shell is the terrestrial world, fixed like the earth; its upper shell is the sky, which spreads over the earth, rounded at the ends, and in between the shells is air.

Hence, Kurma is the microcosm of the world, and because the world is produced from sacrifice, Kurma is the foundation of the sacrificial altar.

Thus it is that Kurma is the world tortoise, Akupara—boundless, yet fixed, holding the earth stable. And, thus it is that Kurma, the kachhapa, is also an allegory of a person who is steadfast in his quest for realization—one who is able to withdraw his sense organs, just as the tortoise draws its limbs within the shell; one who is firmly fixed, but one whose consciousness is limitless.

Aleph Book Company

216 pages; Rs 499

Timingila That Once Was

There is not much known about timingila, except that it used to be a sea creature so large that it could swallow a whale in one gulp. Its existence was known till epic times, and epical heroes on their journeys saw it drifting in the water, like a great big mass, at least eight miles long.

Arjuna, the Mahabharata hero, saw the creature once, when he was on his mission to find divine weapons for the Great War. Standing on the ocean shore, he saw tortoises and crocodiles in the heaving waves and, floating among them, like gargantuan rocks submerged in water, were timingilas.

Rama and his army of monkeys also witnessed the creature in the shoreless sea. After Hanuman returned from Lanka with news of Sita’s captivity in Ravana’s Ashoka Vatika, Rama marched his forces across rivers and mountains to the southern shore at the base of Mahendra Mountain, beyond which was a vast stretch of water, whose other end was Lanka. In the giant waves, they saw alligators and whales and the terrible timingilas that could swallow all the other creatures of the sea, including serpents with flaming hoods. But immense though these beings were, the wind gusts were bigger; they thrust the waves with such tremendous force that even these mammoths were tossed about.

To seek safe passage across this mighty ocean, Rama propitiated Varuna, the lord of waters, by sitting on kusha grass for three nights and praying to him. But Varuna remained unmoved. Angered by the arrogance of the god of waters, Rama stood up in resolve. ‘Watch me split apart these great sea creatures,’ he said to Lakshmana and shot a volley of arrows in the water. Then, mounting on his bow a missile presided over by Brahma, he warned Varuna: ‘Today I will dry your waters till all that remains of your domain is sand.’

Even as he pulled the string of his bow, a great cry arose from the sea creatures as they were tumultuously tossed onto the beach like deluge. A fearful Varuna then manifested himself and stood before Rama with folded hands. ‘I will allow Nala, the son of Vishvakarma, to build a bridge across the ocean,’ he said. ‘And I promise that while the monkey army is crossing, my creatures—serpents, alligators, and the massive timingilas, whose natural instinct is to devour—will refrain from harming them.’ Thus, due to Varuna’s promise, Rama’s army of monkeys was able to cross the ocean free of fear, even though they could see the colossal creatures watching them from the waters below.

In fact, the timingila fish was so feared for its size and ingurgitation that it came to represent the unfathomable—a metaphor for poets and writers. For instance, this is how Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu described the suffering of gopis when Krishna parted from them: ‘The gopis are drowning in an ocean of separation. So great is their pain, it is as though they are being devoured by the timingila.’of waters, Rama stood up in resolve. ‘Watch me split apart these great sea creatures,’ he said to Lakshmana and shot a volley of arrows in the water. Then, mounting on his bow a missile presided over by Brahma, he warned Varuna: ‘Today I will dry your waters till all that remains of your domain is sand.’

Even as he pulled the string of his bow, a great cry arose from the sea creatures as they were tumultuously tossed onto the beach like deluge. A fearful Varuna then manifested himself and stood before Rama with folded hands. ‘I will allow Nala, the son of Vishvakarma, to build a bridge across the ocean,’ he said. ‘And I promise that while the monkey army is crossing, my creatures—serpents, alligators, and the massive timingilas, whose natural instinct is to devour—will refrain from harming them.’ Thus, due to Varuna’s promise, Rama’s army of monkeys was able to cross the ocean free of fear, even though they could see the colossal creatures watching them from the waters below.

In fact, the timingila fish was so feared for its size and ingurgitation that it came to represent the unfathomable—a metaphor for poets and writers. For instance, this is how Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu described the suffering of gopis when Krishna parted from them: ‘The gopis are drowning in an ocean of separation. So great is their pain, it is as though they are being devoured by the timingila.’

Excerpted with permission from Alebh Book Company from the book Adbhut

Write to us at [email protected]