Veenapani Chawla was an actor, director, choreographer, writer and composer and is a name to reckon with in experimental contemporary theatre in the country.

Born of parents from West Punjab who migrated to Mumbai, Chawla was exposed to theatre at a very early age. Before she took up direction in 1980, she had acted in a few plays under Amol Palekar. Her deep and abiding interest in theatre led her to establish the Adishakti Laboratory for Theatre Art Research. The institution was founded as a theatre company in Mumbai in 1981, Adishakti’s main activity then was to create performances that were already scripted. However Chawla was not satisfied. In 1983, she started including research as a part of Adishakti’s activities, out of a need to create a new language for contemporary performance. The base was shifted to Pondicherry. Adishakti has turned 40 this year.

Veenapani Chawla’s belief in plurality helped her move beyond earlier notions of what theatre should be and demonstrate what theatre could be. She was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Puraskar for theatre direction.

in 2010. Chawla had also received a senior fellowship from the ministry of culture, New Delhi and served on the board of directors trustees of the national folklore support centre, Chennai.

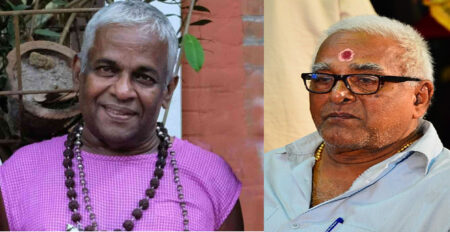

‘A Great Dawn’, ‘Impressions of Bhima’, `So What’s New’ were some of the plays directed by her. In 1985, she was mesmerised by Koodiyattom after she saw a performance by the maestro, Ammannur Madhava Chakyar, at the School of Drama, Thrissur. The rave reviews that the two productions ‘Brhannala’ and ‘Ganapati received across the world are eloquent testimonies of her ability to fuse tradition with modernity. Veenapani Chawla passed away in 2014 leaving behind a rich legacy. India Art Review is reproducing an interview of Veenapani Chawla where she talked about the significance of Koodiyattam and how it helped in her theatre journey.

Did you undergo training in these two arts?

After my tryst with the age-old Sanskrit theatre here in Thrissur in 1985, I came for an extended stay as directed by G.S.P. (Prof. G Sankara Pillai, director of School of Drama). I stayed at Irinjalakuda and travelled to Chavakkad to learn Kalaripayattu in the morning: Evenings were spent for training and discussions with Madhava Chakyar. This went on for many years. practised Koodiyattom to understand the theory better.

What do you find so special about Koodiyattom?

For instance, I understood how breathing was significant in the evocation of bhava. There was an underlying rhythm behind this. I felt that rhythm in this art form was like a language, which could convey many meanings. Rhythms replaced the function of a text in Koodiyattom.

Is it the pattern or tempo that communicates?

The way you make use of it with visuals go a long way in communicating the images created.

But have you not seen that Kathakali is also highly rhythm-oriented?

It has not struck me as much. As for Koodiyattom, the meaning of a performance is complete only with the beating of the mizhavu.

In the Laboratory, are you using the same rhythms employed in Koodiyattom?

No. Our policy is not to follow the codification of rhythms and breathing as such. Codifications are only guidelines. The artistes are encouraged to develop their own rhythms based’on them.

How far could you explore the seven psychological centres of energy for performance?

We have been working a lot on the Chakras. They are involved in all the performing arts and correspond to the centres of energy for the movements.

What are the routine activities of Adishakti?

We are continuously engaged in research in different departments of theatre. I have been lucky to get Usha Nangiar from Kerala and the most celebrated disciple of Guru Madhava. Chakyar. The services of the mizhavu exponent Hariharan are really praiseworthy. Two French artistes also collaborate with us on a permanent basis.