The stories of British civil servants who strived to give India’s past an authentic narrative.

Varanasi, considered one of the oldest surviving cities, was in the news recently when PM Narendra Modi inaugurated the first phase of the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor. Newspapers and magazines published maps of the section of this holy city showing the spread of the corridor and its link to the ghats. Varanasi, to many, is a source of knowledge and research, and the place of culmination of the life cycle at the same time.

Exactly two centuries ago James Prinsep, a multi-faceted Englishman and a scholar, fell in love with Varanasi and gave the city its first map. Not just this, Prinsep is also credited for having constructed an underground tunnel for draining a swamp from the lowest parts of Benaras, as the city was called then. Prinsep, an engineer, scientist, linguist and an architect, formed the Benaras Literary Society in 1822. When he moved to Kolkata, he became the Secretary of the Asiatic Society (He later became the founding editor of Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal). Of the numerous contributions of James Prinsep, the one that stands out is his remarkable effort to enable an in-depth study of India’s past, which till that time was widely believed to have begun with the reign of the Mughals.

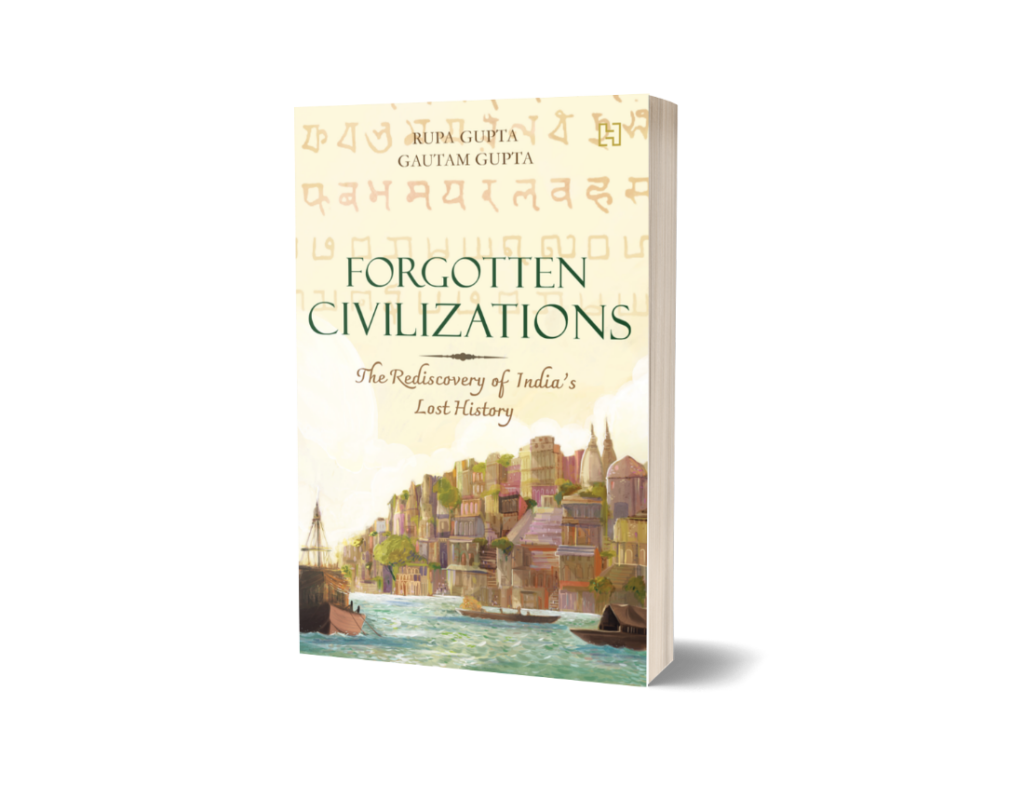

To his credit, Prinsep lifted the veil from earlier Indian inscriptions that laid the foundation of research in Indian history by decoding long forgotten scripts of Brahmi and Kharoshti. Well, one can go on and on about this man who ironically did not have much formal educational background. Prinsep is just one of the 15 Indophiles featured in Forgotten Civilizations: The Rediscovery of India’s Lost History. What’s spectacular about this book is the way the authors have highlighted the research and documentation done by these largely unsung heroes who were simply driven by their curiosity and enthusiasm to give India’s past an authentic historical narrative.

The Birth of a Font

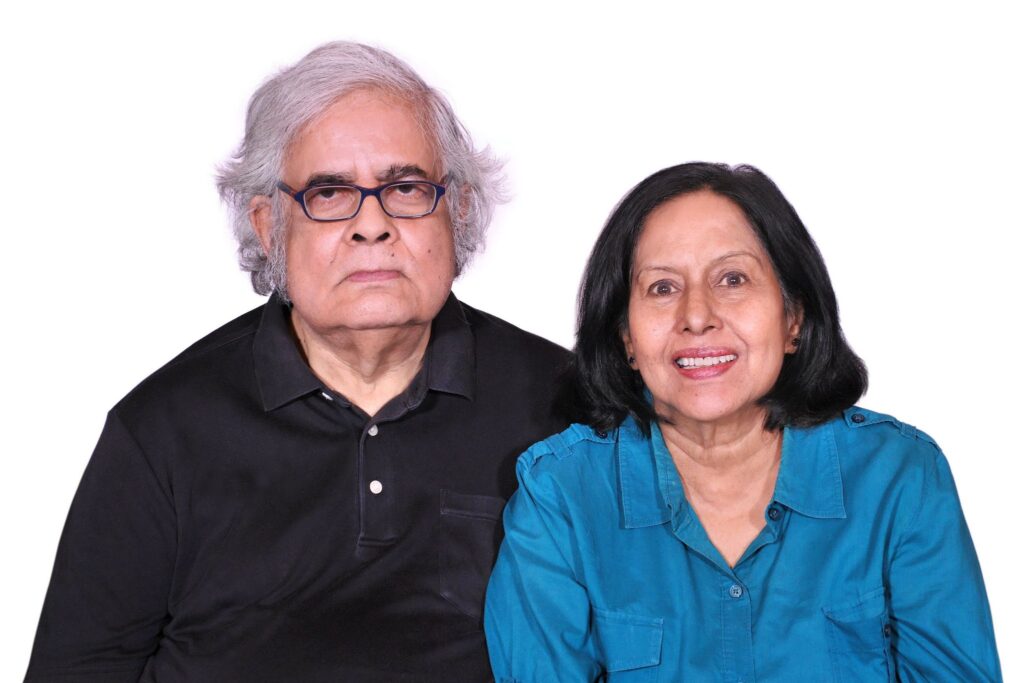

Rupa Gupta is a writer and editor and Gautam Gupta is a retired bureaucrat who has special interests in researching the Raj period and Germany during WW II. In this book, the authors treat the readers to several interesting facts about the contributions of these Indophiles. Take the case of the earliest known set of Bengali font. It was Charles Wilkins, an employee of the East India Company, who designed the first typeface of the Bengali script when he was just 28. This was in 1788 and thanks to him, Bengali became the first Indian language to appear in print – a book titled A Grammar of Bengali Language authored by another Englishman – Nathaniel Brassey Halthed. Both Wilkins and Halthed feature prominently in Forgotten Civilizations. Their contributions cover a wide range of achievements that have left an indelible mark in our progress as a society and as a nation.

Wilkins went on to study Sanskrit and subsequently translated the Bhagawad Gita in English in 1884, which had a far-reaching influence and impact on Europeans. The translated work also enhanced their understanding of Hinduism back in the 1880s.

Forgotten Civilizations (Hachette)

Mythology and Translations

Forgotten Civilizations opens with the chapter on William Jones and one learns of how this Sanskrit-ist solved a great historical puzzle – Sandrocuttus. Even as contemporary historians were scratching their heads in search of the meaning, it was Jones who identified Sandrocottus as Chandragupta Maurya. Jones, while researching contemporary Greek writings, discovered that the Greeks had a penchant for changing the names of people and places. He also identified the city of Errannoboas as Patliputra, thus solving two riddles and matching the account of Greek explorer and ethnographer Megasthenes with Indian history.

A legal eagle, Jones was also successful in translating seven volumes of Manusmriti in English. His other work included the publication of Mohammedan Law of Succession and a similar work on inheritance. The authors also dedicate a chapter to the contributions of Sir Monier Williams, who is credited to publishing the first Sanskrit-English dictionary in 1872.

Traversing through the book, one could be awestruck how Englishman Monier Williams admired the Indian texts Ramayana and Mahabharata. The authors highlight how he claims that the beauty of description in these texts cannot be surpassed by anything written by Greek author and poet Homer. Right at the end, the book also describes the contribution of Sir John Hubert Marshall, who was the English director general of the Archaeological Survey of India (1902-1931). It’s surprising that we know so little of the man who pioneered the cause of establishing the antiquity of the Indus Valley Civilization and worked towards the restoration of monuments at Agra, Sanchi, Lahore, Bijapur and Ahmedabad. In fact, his commitment to the cause and subsequent achievement becomes even more praiseworthy when the reader realizes that these conservation work could only be started after evicting government offices and military establishments from most of these places.

The 15 Hidden Gems

The only thing lacking in the book perhaps is a timeline chart, which could have helped the reader to chronologically place the events and discoveries featured in this book. And yes, photographs of these great souls would have added to the book’s charm. Maybe we are too attuned to spreadsheets and social media to seek such frivolities in a superb book. Forgotten Civilizations is a good read for anyone who has a passion for evolution of the historical, linguistic and archeological studies of India. One does not easily find names such as that of Princep or of most of the Englishmen such as Jones and Marshall featured in Forgotten Civilizations figuring prominently in the annals of British-Indian history. And it is here that this compilation scores.

Write to us at [email protected]