Terracotta sculptures have been of increasing interest to musician-dancer-lyricist Sadanam K Harikumar. A take on the all-round artist who won a Kerala Lalithakala Akademi honour recently.

The schoolboy spent his leisurely hours with pot-makers, trying to mould small figures from clay. Then, into his thirties, Sadanam K Harikumar resumed that aesthetic engagement. This time, too, the location was outdoor. Only, a good 2,500 km away from his Kerala village. The young teacher at Santiniketan was kneading mud when he saw one day an iconic artist passing by. KG Subramanyan!

Impulsively, Harikumar called the professor emeritus. The veteran took a round of the amateur’s studio. “KGS was pleasantly surprised,” recalls Harikumar about the encounter in the early 1990s. “He found my work fairly good. And remarked that it bore no style of Santiniketan; instead looked unmistakably Dravidian.”

Subramanyan (1924-2016), too, was originally from Malabar. Growing up in Koothuparamba east of Kannur, he joined the freedom struggle. The imperial British regime sent him to jail, where fellow Gandhian K Kumaran was briefly his cell-mate. “Till he saw my sculptures, KGS knew me as Kumaran’s son and a dancer-musician,” says Harikumar. That meeting, though brief, was a highlight of his four-year stint Visva-Bharati University as a lecturer with the Kathakali department.

A serious illness abruptly ended Harikumar’s tryst with West Bengal. Monsoon-time cerebral malaria forced his return to rugged Peroor of Palakkad district in 1993. Recuperation took months. The subsequent year, he re-joined Sadanam Classical Arts Akademi his father had founded six years after Independence.

Slowly, sculpting yet again found its place in a range of Harikumar’s creative activities. The potters in the neighbourhood had disappeared in a changed era, and the artist anyway had gained a broader vision about sculpting. A quarter century down the line, Kerala Lalithakala Akademi honoured him recently. Harikumar figured on the 2020 list of awardees the state’s apex institution for fine arts gave away last week.

Terracotta trials

Harikumar, 63, sports an amused smile when he recalls his schooldays. “My father ran Sadanam as a multi-activity institution. Not many in the family had the time to guide me,” he says. “I’d roam about once I was back from school. The potters’ colony in the vicinity used to be one attraction. I’d join them and try making minor objects…elephant, old woman, mortar and pestle, emperor Mahabali…”

Into teenage, there was a certain graduation in the profile. “I began moulding those clichéd stuff: woman holding the water-pot, street vendor, snake-charmer,” he says. “None of it was a studied work. Neither did I have a trainer. Yet at high-school competitions, I invariably won prizes.”

There was a break in this pursuit when Harikumar joined college. First, at Ottapalam, 12 km west of his house and then during his graduation from another in Irinjalakuda in adjacent Thrissur district. Dancing Kathakali and also singing for the dance-theatre were his prime passion those five years. That continued during his years pursuing a Master’s in Malayalam even as he retained his interest in painting. “I drew a Radha-Krishna series that time, much to the appreciation of my well-wishers.”

Then, at age 31, Harikumar boarded a train to Calcutta and beyond. At Santiniketan, he also began pursuing doctoral research. “Amid that I started working on clay,” he reveals. “A standing Ganesha was my first idol on the campus. I gifted it to my guide Sitansu Ray.”

Thus dawned the idea of terracotta on Harikumar. Rabindranath Tagore’s institution proved to be a fertile land to work regularly on hollowed-out ceramic and expose them to fire. The spirit of it was rekindled even when Harikumar was back in Kerala in his mid-30s.

On Kathakali masters

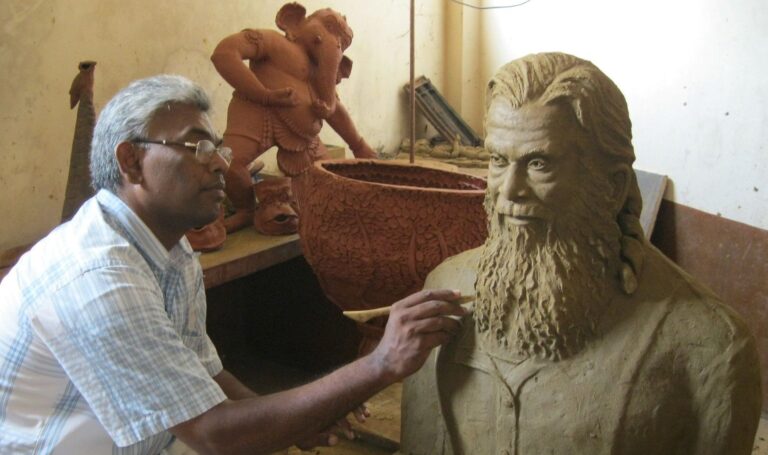

Soon, in 1994, Harikumar came out with a bust in terracotta of Kathakali titan Pattikkamthodi Ravunni Menon who redefined the aesthetics of the art-form in the earlier half of that century. It won appreciation from Menon’s frontline disciples Keezhpadam Kumaran Nair and Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair, on whom, too, Harikumar later made sculptures.

More masters of Kathakali found portrayal as statues: Thekkinkattil Ravunni Nair, Vazhenkada Kunchu Nair (dancers), Venkitakrishna Bhagavatar (music), Venkichan Swamy (maddalam) and Harikumar’s Carnatic guru C S Krishna Iyer besides the artist’s parents (K Kumaran and Sarojini Amma).

Alongside this journey, Harikumar has come up with several sculptures of classical and contemporary genres. Sometimes, using cement or going for relief. Otherwise, in terracotta. One such is Karmayogam, which fetched him the Akademi’s special mention. The six-foot work portrays a man who has risen after death. With a wreath on his belly and eager crows around, it symbolises the essence of life as a cycle.

Harikumar, simultaneously, is a painter. Besides pencil-drawing, watercolour and oil-on-canvas, he works with the mouse for images on the computer. In Carnatic, Harikumar’s Malayalam compositions have won special appreciation. He has penned and staged 18 Kathakali stories after choreographing them with novelties. The latest such play, Sikhandi, is to be premiered at Sadanam this weekend.