This month three years ago, Burundi passed a decree that banned women from performing the famed Karyenda drums. India has a similar Manipuri percussive dance where men play the horizontal Pung.

Both are a mere spot if you check them on the maps—of Africa and India respectively. Burundi, down the middle of the Mother Continent, is as small as Manipur is for the Asian country, tucked away in the Himalayan foothills. The equatorial nation and the north-eastern state are landlocked, with mountains making the topography largely rugged. And the demographics defined by a grand coexistence of ethnic peoples.

Again commonly, the native populations unveil the best of the region’s cultural heritage. This write-up, though, will restrict the gaze to just one kind of an indigenous drum. Burundi’s Karyenda and the Pung of Manipur.

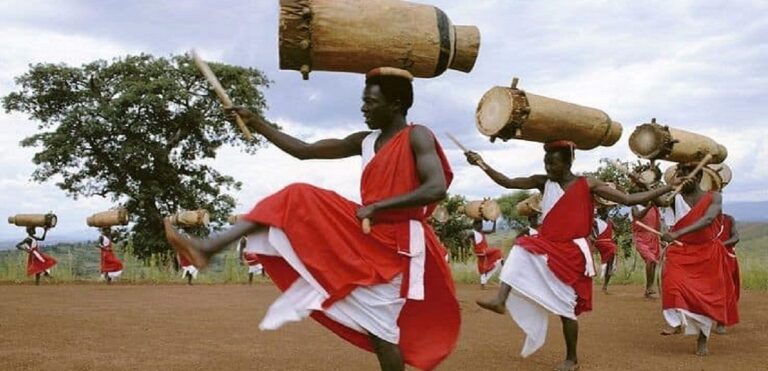

If one went by the way the two instruments produce sounds, there’s no big scope for comparisons. But, they share a striking similarity in the vigorous use of the body in sync with the rhythmic beats, thus making both performances by both Burundi and Manipuri men a visual treat as much as they are music for the ears.

Dance and play

The vivacious ensemble by the drummers of Burundi bears a ritualistic value to their performances: they classically perform at ceremonies allied to births or coronations, feasts, VIP visits or rites meant to awaken ancestral spirits or exorcise evil beings, besides at funerals. The Karyenda drums, which are considered holy and symbolic of regenerative powers, are a source of not just cascading beats. They function as a trigger for the players carrying them to sing as well as dance.

The vigour in the movements is uncannily similar to that of Manipuri artistes of Pung Cholom. Only that, they have the drum hung from the nape of the neck to position it horizontally along the waist. The taps are with the palms and fingers—there is no use of sticks, which is integral to playing the Burundian drums.

The Karyenda, however, has its only one face to drum. On the ground, it stands up, as is represented in Burundi’s national flag that was in vogue for four years from July 1962 when the country won independence from Belgium. This is unlike the case with the Pung, which has its both faces (to the left and right of the player) receiving the taps and rolls. The hollow cylinder of both the drums, too, are used to produce sounds—with even the leg sometimes employed in the case of the Karyenda. That is when the drum is placed on the head of the artiste, who walks with measured steps.

For the record, the Pung, too, is said to have one beating face when it was introduced 18 centuries ago. That model, by Manipur’s king Khuyoi Tompok (154-264 AD), evolved over the decades to eventually pave the way to what is Meitei Pung today, with its two beating faces. In its present form, Pung Cholom has its line-up of artistes—linear or circular. In the case of the second, they go for gay abandon rounds (after nodding the white turbans stylishly off the head). Simultaneously, there is a rotation of the bodies with each step—only to smoothly land and then dramatically produce drum rolls.

No women norm

If the Pung artistes produce an occasional roar (in the off-beat gaps), the Burundi drummers go for simultaneous singing. The traditional songs are poems, largely on heroism. The drums would total a minimum of one dozen (invariably an odd number)—often a semicircle around a central drum.

In the new age, though they also disseminate political ideas or social messages. The drummers have been performing abroad since the 1960s.

Burundian society has been strongly patriarchal, while Manipur has had its Meitei women enjoying much higher degrees of freedom thanks also a history of matrilineal set-up. Pertinently here, in October 2017, Burundi’s President issued a decree that limited the use of the Karyenda to just men. The role of the females got restricted to performing the folk dances that would accompany the drumming, drawing protests, but to no avail. Historians say women playing the drums isn’t an entirely modern phenomenon: records show them handling Karyenda in the early 15th century, according to historians. In fact, certain parts of the drum have their names after parts of the female body.

Whatever, the ruler stuck to his stance, also demanding Karyenda performers to seek official permission in certain cases. The Ministry of Culture would collect a fee (US$260) for a show at unconventional (social or political) events. Motto: counter an increasing marketization of the art, which Unesco in 2014 recognised as an “intangible heritage of humanity”.

Back in Manipur, Pung Cholom by Hindu Brahmins retains its energy drawn from local martial arts (Thang Ta and Sarit Sarak) besides the vintage Maibi Jagoi dance. The acrobatics are breath-taking, but then there are passages of slow rhythms too. The climax, yes, is explosive.