The Covid-19 pandemic has robbed Kadavallur Anyonyam, a unique academic exercise for the preservation of Rigveda, of its sheen this year.

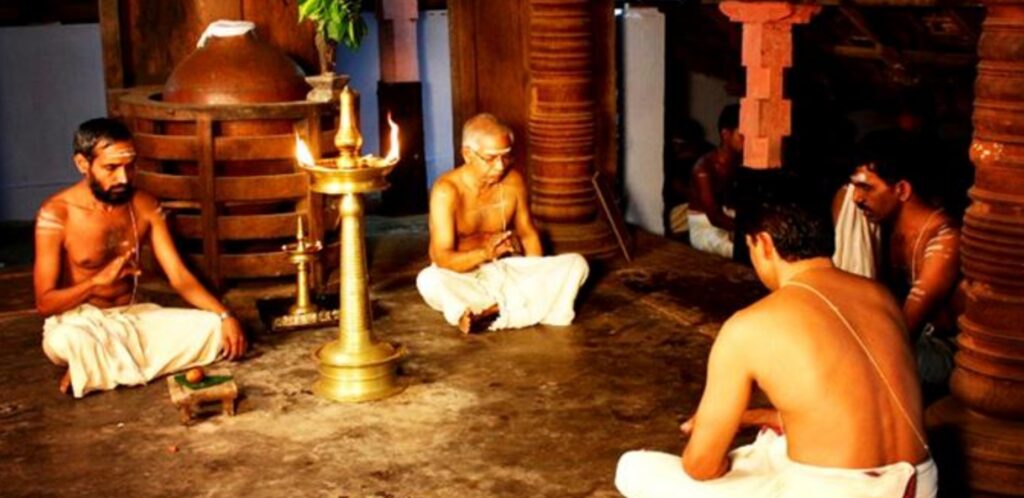

Sree Rama Temple in Kadavallur, a remote hamlet in Thrissur district, hogs much media attention every year in November. For, the singular Vedic exercise of Anyonyam is held there from the first of the Malayalam month Vruchikam for eight days. (This year from November 16 to 23). Students from Brahmaswom and Thirunavaya Madhoms, the only two centres of excellence for the studies of Rigveda assemble there for a competition that is noted for its byzantine procedure and other cultural programmes associated with it.

No one knows the beginning of this unique academic exercise for the preservation of Veda. Historical records signpost to its conduct until 1947. But it was revived in 1989 by the Kadavallur Anyonyam Parishad and ever since it has been held without fail.

The contestants from the two madhoms are selected to take part in Anyonyam through rigorous tests known as ‘kizhakku – padinjaru’ (east-west). The style of rendition of Rigveda is esoteric and it is tutored with the movements of the head for the correct intonation accompanied by gestures. For, in the chanting of Vedas, swara is most important. Brahmin boys are initiated into this art at an early age and they undergo arduous disciplining for several years under the prying eyes of ‘Othans’ (Vedic priests). Chanting of the 10,472 riks can be perfected through a systematic practice for which a ritualistic and highly disciplined lifestyle is imperative for the students.

Make no slip

A spirit of healthy competition and rivalry is discernible even in the preparations well before the event. On the eve of the opening day, the two teams check into separate abodes prescribed for them. The ancestral home of ‘Achuthahtu’ is allotted for the Thrissur contingent while the Thirunavaya team goes to ‘Pakshiyil’. ‘Moothemmars’, owner of these homes, look into the comforts of both the students and gurus until the competitions are over.

No interaction between the members of the two troupes is entertained on these days, not even among the relatives. Even the spatial distribution of the contestants inside the temple smacks of rivalry as they face each other. The traditional rivalry is ascribed to the fact that the two madhoms were patronised by the Maharaja of Cochin (Thrissur) and Zamorin of Calicut (Thirunavaya) who were traditional enemies.

The modes of the oral test are technically called ‘Vaaramirikkal’, ‘ratha’ and ‘jata’. Interestingly they are held in the night. One has to recite a particular ‘varga’ of Rigveda without any slip during the first test. If the memory fails, a helping hand is rendered by the gurus, but strictly through gestures which form an intrinsic part of the training as well. Incidentally, the mudras (hand gestures) are so effective that two pundits can communicate the entire Rigveda through mudras alone, maybe in six hours. Further, this is peculiar to Kerala. A failure in this test is considered disgraceful, so much so that the candidate may disappear from the venue even without the knowledge of his compatriots.

Rigveda, meant for all

While Vaaramirikkal is held prior to the supper, both ratha and jata for the winners Vaaramirikkal, are conducted during the supper. These are more complex as they demand an admixture of both ascending and descending order of recitation of select verses. One may wonder whether such practices are objectionable in Veda aalapana; but it is justified since it is only an examination.

‘Mumpilirikkal’ (sitting in front of the examiners or in front of the deity), ‘Kadannirikkal’ (sitting in the inner parts of the temple for higher tests) and ‘Valiyakadannirikkal’ (more severe tests) are intricate tests which are challenging. Only those completed the first three are eligible to appear for this. Not many have come out through this ordeal successful. In the recent past Mookuthala Panthavoor Subramaniam Namboodiripad had graduated the Valiyakadannirikkal, but he is no more now.

A ritual that is quite anachronistic and not much encouraged nowadays is the chanting of ‘Rama hare……’ in the highest pitch by a group of Nairs as they move around the temple. The purpose was to drown the Rigveda renditions so as not to reach the lower classes for whom listening to Vedas was proscribed.

Ever since its revival in 1989, a host of cultural programmes were organised every day. Artistes from across the country perform without any remuneration. National seminars have become a regular feature. A slew of research papers has been presented so far and published in accredited magazines.

The Covid-19 pandemic has robbed the Rigveda debate of its sheen this year. The temple that used to wear a festive look every year during Anyonyam appears practically orphaned except for eight people just to chant the Veda for the propitiation of the deity.

Also Read: Valiya Kunjunni Raja: The Less-Hailed Architect of Kalamandalam