Without Tharun, Yazh, an ancient instrument would not have taken birth in modern times

The recently released Mani Ratnam film Ponniyin Selvan not only depicts a segment of Tamizh history but also the rich cultural heritage that the Tamizh community inherits.

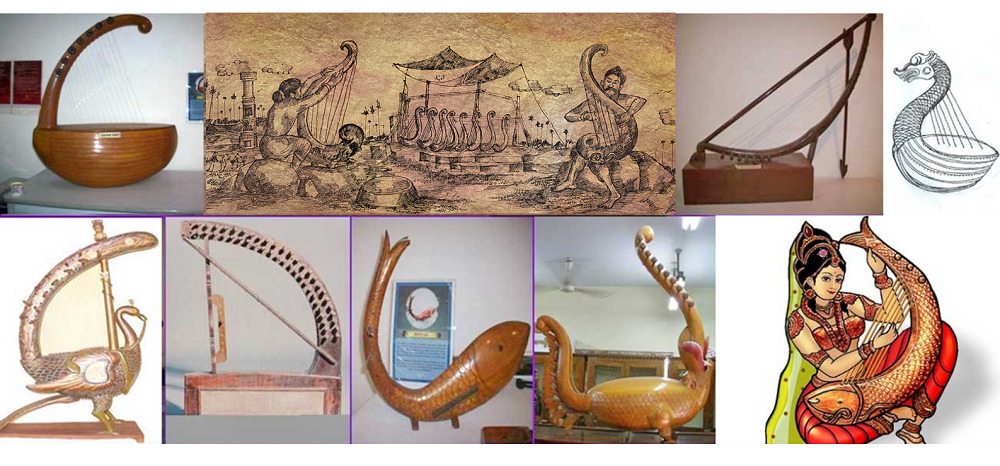

Kalki Krishnamurthy’s novel Ponniyin Selvan is an excellent documentation of the aspirations and cultural values of people. The book is so engrossing that the readers transcend time and travel back to the ancient past of Tamil Nadu where they encounter some aspects of culture and some artefacts that once used to be their identity markers. In Ponniyin Selvan, like in many classical texts in Tamizh, there are repeated references to superior music traditions and musical instruments. One among them is yazh, which is a string instrument that the Tamizh community treasures as an integral component of their ancient music tradition.

When the current generation of musicians experiment with the most modern string instruments, largely in the western cult, a young guitarist with a solid interest in his own heritage is on a mission to revive the ancient musical instrument yazh(Yaazh). Chennai-based Tharun Sekar had a Himalayan task while reviving yazh in 2019 as in modern times nobody has ever heard its music.

To revitalise an art form along with the instrument was a challenge to Tharun. Texts like Silappathigaram, Jeevaga Sindhaamani, Perum Panatru Padai, Saivathirumurai, Thirukkural, Thiruppalli Ezhuchi and many others have plenty of literary and aesthetic descriptions of yazh and its beauty. References to yazh are abundant in scriptures and texts that date back to 3000 years ago. Tholkapiyam also has a detailed account of yazh.

For example, Porunaratru Padai from Pathupaattu has lines 25-47 describing the structure of a yazh. Vaidehi Herbert translates these lines as

The Pālai lute is shaped like the

hoof track of a deer, its pot

section has two parts and is slanting

on the sides, its tightly tied leather

top in the color of flame from a lamp,

its sewn covers resembling the

orderly, delicate hair on the beautiful

stomach of a pretty, pregnant woman

whose early pregnancy is not known

to others, its nails that are driven in

to hide the holes appear like

the eyes of crabs that live in tunnels,

its sound hole without tongue has the

shape of an eighth day crescent moon,

its long and dark stem is like a

cobra’s lifted head, its frets tied tightly

close to each other are like pretty

bangles on the forearms of a dark

woman, its strings plucked by fingers

are tied, long and faultless like pounded

fine millet with chaff removed,

and its body is beautiful like that of a

fragrant, decorated woman, sweet

like possessing a goddess within, faultless,

making even wayside bandits lose

their harshness and drop their weapons.

A demanding task

Porunaratru Padai hints at how yazh is played: Stroking with the index finger, strumming with the thumb and index fingers together, and plucking gently and strongly the different strings, it creates vibrating music, sung with lyrics. However, sadly, like many other cultural treasures, this instrument gradually became extinct. Having nobody manufacturing them, none trained to use them, they became rare pieces in museums. Losing the artistic and cultural heritage of a people can mark the gradual death of their civilisation itself.

Yazh, which is a lyre or harp-like string instrument, has its origin in India and Sri Lanka, according to Janani Rajeshwari, a music enthusiast and journalist. When Tharun started, he did not have any idea about the voice quality of the instrument or the know-how of its architecture. The recreation was a demanding task and at one point it appeared to be unachievable.

Non-functioning models are available in three museums in Chennai (in Poompuhar handicrafts, Raja Annamalai Manram and Egmore museum). They are also found in some museums in Kerala and Sri Lanka.

With the help of Madurai-based architect and musicologist M. Sivasubramanian, Tharun made great progress in unearthing this forlorn instrument, bringing it back from the past to the present. Though there are different versions of the story of its origin, the one that is most popular ascribes the music of yazh to the resonating sound that the string of a bow produces when touched by the hunter/ archer. It is interesting to see a weapon, a bow, becoming an instrument of music!

Yazh is different from its western versions like harp and lyre. It is believed that yazh in its initial phase of development, took the shape of a mythical animal called ‘yali’ which is a kind of dragon. It was later made into the shape of a peacock, bull, fish and the like.

Harmonic curve theory

Tharun says that art, science and maths are involved in the making of Yazh. It is designed based on Harmonic Curve theory, based on calculations of the length, diameter and materials used to generate intended music notes on the strings.

Tharun found that the best wood to use for making yazh is jackfruit tree or red cedar and decided to manufacture more of them, ensuring their compatibility with modern day demands. This was important as there are currently no practitioners of this instrument.

To popularise it and to bring it back to the present day, certain compromises had to be made with the original and ethnic versions.

The original yazh was made up of goat skin glued to the structure with turmeric and tamarind-based paste which functioned as the adhesive. However, tuning the instrument became very difficult as it had to be heated every single time. Therefore, bracketed hooks were added to the original design.

Use of red cedar made the instrument less heavy. The size of the instrument was also reduced after the initial recreation in the original scale.

This made its logistics easy. In its return, yazh is tuned to the global C-major scale. This made it possible for anyone with skill at playing guitar to use yazh. The original goat skin gut was replaced with metal strings.

Tharun’s present endeavour is to churn out an electric yazh, making it more appealing for youngsters. Tharun and his fellow music lovers made an album named Azhagi which became the world’s first ever recorded song using Yazh.

For any elements of culture to survive, there should be people who mark them in their cultural memory and take efforts to save them for the future generations. The demands of the day encourage us to rush through the mundane, many a time sacrificing an ethnic identity and rich traditions that we once cherished. Instead of museumising our cultural artefacts and the elements of our rich heritage, understanding treasures of our civilisation, history and initiating steps to revive, preserve and pass them over to the next generation will work better. And that is exactly what Tharun did by reviving yazh.

1 Comment

Wow ✨️