Rajitha Ramachandra Pulavar and her team gave a new meaning to Tholppavakkooth and the body politics went in for a change.

Rajitha Ramachandra Pulavar and her team gave a new meaning to Tholppavakkooth and the body politics went in for a change.

It is intriguing to notice that an art form dedicated to a female deity does not sanction women being a part of it because of the constrained notions of purity which is nothing but enforced body politics.

Tholpavakoothu, an art form more than 1000 years old is conducted in Bhadrakali temples in Kerala, to worship the fierce female deity. However, females never performed it till last year. This issue of gender parity was addressed by Ramachandra Pulavar, the Padma Shri recipient, the most famous practicing puppeteer, after he took puppetry out to the applied theatre setting, to society, and to a larger audience.

Questions about gender parity in this temple art were discussed for the first time when Ramachandra Pulavar allowed a foreign woman to enter the Koothu Madam’s (a play house built on temple premises where the Koothu is performed) steps as she was the only woman left to watch the overnight Tholppavakkooth show. Infuriated protectors of culture and rituals banned him from performing at certain Koothu Madams. This was the turning point in initiating a change for females coming forward to practice this art form.

With Ramachandra Pulavar’s endorsement, Rajitha Ramachandra Pulavar, his daughter, pioneered the Pentholpavakooth (female leather puppetry) by taking this art beyond the temple boundaries. All the artists and puppeteers in Rajitha’s team are women and they are involved in the making of puppets, setting up the stage, creating other materials, and even loading the necessary props onto the vehicles while commuting to places of performance. Pentholppavakkooth makes use of shadow puppetry as a tool while addressing existing inequalities. Their first project was the staging of a female’s different developmental phases from birth to adulthood that discussed many social evils like dowry.

The same project emphasised the importance of breastfeeding too. The gender aspect of this Paavakkooth made the Kerala government to approach the team to use this art form to promote menstrual hygiene and endorse the use of menstrual cups.

Purity of the female body

The question of gender became a concern as the literature of Tholppavakkooth began to deal with social issues when this temple art was reincarnated into an applied theatre format. As it was taken out from the margins of temples, the notion of purity of the female body was more or less reconstructed in the same way the artists then made amendments to the traditional stage structures, materials, deerskin, fire torches and literature.

Women were initially given roles to sing for female characters, like Sita, Mandodari, Desdemona, Yasodhara, and others. As Rajitha’s Pentholppavakkooth now found its way into the larger cultural spaces, even though within the temple premises women cannot be a part of this art, they are able to perform to a larger audience outside.

But this artistic revolution was confronted by many traditional Tholppaavakkooth practitioners. There have been several occasions of cyber attacks on social media when Pentholppaavakkooth was being promoted. Some of the young girls who were part of the team were scared but never wanted to give up.

Many of these artists are school and college students who pursue their passion for puppetry. Women have broken the bias by offering public performances in various cultural centres. However, they do have concerns and these are still based on the traditional cursory norms of purity of the female body.

Koothu Madams do not admit female artists as Tholppavakkooth will be staged there for 21 days or more, which usually interferes with the normal menstrual cycle of females. As a menstruating female entering the temple premises is considered a taboo and the notions of purity associated with the female body have always been part of the Hindu ideals and rituals, these women are not permitted to touch the traditional puppets.

Also, the practitioners of Tholppavakkooth who are rooted in patriarchal beliefs asserted that women are not capable of learning the innumerable slokas to be recited at the Koothu Madam. Even when the Koothu Madams underwent certain changes, accommodating females within them could not be thought about. Moreover, treating the intellectual ability of women as inferior to that of their male counterparts was one of the reasons for this social exclusion.

It is at this juncture that an all-women leather puppetry team established that women are not only capable of learning the prescribed slokas but are also efficient and creative in transforming this temple art into applied puppetry to speak about the social inequalities to which they themselves are subjected. As T.M. Krishna points out, art is never an accident but is deliberate and conscious. There has to be a deliberate attempt to make the vistas of the art open to everyone without marking boundaries by gender, caste, or regionalism.

Agents of social change

To preserve an art form, it needs more practitioners and, as Ramachandra Pulavar says, both women and men are talented and the skills become palpable only when opportunities are given.

These women puppeteers are striving hard for opportunities to assert their identity as women, as artists, as humans, and as agents of social change. They hope for a day when those divine premises transform into more inclusive spaces that accept these women puppeteers as artists by not discriminating them as inferior to males.

Film enthusiasts who flock to the most celebrated International Film Festival of Kerala (IFFK) must have certainly noticed its logo but might have failed to associate it with one of the oldest temple art forms known as Nizhalppavakkooth or shadow puppetry.

Shadow puppetry is the precursor to cinema as it too plays with light and shadows. Stephen Herbert, the acclaimed historian and film critic, stresses the importance of shadow puppetry by calling it a prelude to cinematography.

Dadasaheb Phalke, the father of Indian cinema, said it was shadow puppetry that inspired him to venture into the world of motion pictures. IFFK’s logo represents the character Lanka Lakshmi, from the Ramayana, in her majestic appearance after the befallen curse on her was taken away by the touch of Hanuman.

However, this temple art was on the verge of extinction, while different editions of IFFK had been thriving. How did this art form survive?

Tholppavakkooth or shadow puppetry using leather puppets is an ancient Indian temple art which has many parallels in the entire Indian subcontinent. It is known by different names such as Togalu Gombeatta (Karnataka), Tholu Bommalatta (Andhra Pradesh), Tholu Bommalattam (Tamil Nadu), Chamdyacha Bahuliya (Maharashtra), Ravana Chhaya (Orissa) and Chhaya Natak (Gujarat).

These forms of shadow theatre in an era, when radio, television or other similar audio-visual media were non-existent, managed to impart knowledge of Hindu epics in ancient India. However, many of these art forms witnessed a gradual death as there were no practitioners to keep them alive.

Tholppaavakkooth is performed in parts of Tamil Nadu and Kerala in connection with temple festivals. It uses leather puppets made by artists to narrate stories from the Kamba Ramayana, written by the Tamil poet Kambar.

In Kerala, it is mostly practised in Malappuram, Palaghat and Thrissur districts.

Etymologically, this compound noun is made up of three words — thol (leather), paava (the puppet) and kooth (the performance). The lead artist is called a Pulavar which means the scholar or pundit. Tholppaavakkooth, of Kerala survived, though it was vulnerable to extinction at a point. There was a sudden revival of this temple art form by taking it out of the temple premises to the more publicly accessible spheres of cultural interaction.

The myth behind Tholppavakkooth

The myth that explains the origin of this art form says that the Darika Nigraha (killing of the demon Darika by Bhadrakali) occurred at the same time as Rama killed Ravana. As Bhadrakali was fighting the demon, she could not witness the culmination of the battle between Rama and Ravana. Therefore, she approaches Lord Shiva, her creator. He asked her to reside in the “sacred land of Kerala” and assured that a screening of all episodes from the birth of Rama till the coronation would be conducted in her temples exclusively for her, every year, in the form of shadow puppetry using leather puppets.

From January to June every year, Tholppavakkooth is performed in temples in Kerala. This art form later found its way to the temples of other deities.

When Tholppavakkooth is performed, the idol of Bhadrakali will be placed on a pedestal before the stage where it is presented. The stage on which Tholppavakkooth is performed is called Koothu Madam. Around 85 temples in Kerala have permanent Koothu Madams. Each Koothu Madam has a length of 41 feet, a height of 12 feet and a width of 8 feet. It has a screen with black and white cloth, similar to the movie screen, which is called ‘Aayappudava’ and is presumed as sacred as it is believed that this piece of cloth is worn by the goddess.

The white segment of this cloth symbolises the sky and the part in black stands for the Earth and the nether world (Paathaaalaloka). Behind the white part of the screen, the artists hold the puppets. Coconut halves are used as lamps that carry the oil and the wick and these lamps are placed at equal distances from each other on a beam like wooden structure named Vilakku Maadam (lighthouse).

Usually, 21 of such lamps are used to produce the puppets’ shadows on the white screen.

Traditionally, puppets were made of deer skin as deer is considered a sacred animal in Hinduism. A more practical reason might be the durability of the deer skin and its compatibility with rough handling.

Depending on the literature, in particular when the character description includes the skin tone and it denotes specific colours, puppets are painted. For ritualistic performances, natural colours are used. Different mudras discussed in the Natyasastra are used, among which the most common being the Chin Mudra (the symbol of peace).

The slokas and songs are composed in Tamil, Sanskrit and Malayalam.

The complete version of Tholppavakkooth stages all episodes from the Kamba Ramayana, requiring the artists to learn and recite over 3,000 slokas which will be accompanied by instruments such as conch, chenda, chilanka, ezhupara, ilathaalam and kuzhal.

It will take a minimum of 21 days to perform all episodes of the Kamba Ramayana, with each day’s performance beginning at night and ending in the early hours of morning. The show opens with a Kelikott (an announcement using the traditional chenda) and a prayer called Kalarichinth. As per the customary practice, Tholppavakkoothis is conducted over 7, 14, 21, 41 or 71 days and may require about 200 puppets and 40 puppeteers. Within the temple premises, it is done with all the ritualistic norms that are part of this art form.

From temple art to applied puppetry

In the beginning, the financial benefits of the puppeteers were limited. They used to have performances in various temples for a few months and then, for the rest of the year, they had to depend on other means of living. This has resulted in a steady decrease in the number of practitioners, just as it is the case with many other traditional temple art forms like Kathakali and Koodiyattam.

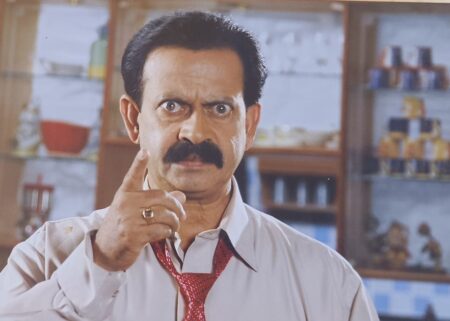

Ramachandra Pulavar belongs to the 11th generation of a family of puppeteers who adhered to all traditional norms and considered this art as divine. His late father K L Krishnankutty Pulavar and the famous Koodiyattam artist Venu G of Natana Kairali were bold enough to experiment with this temple art form.

They acknowledged it not just as a ritual but as an art form by bringing it out from the temple premises, thereby making it accessible to a larger audience on various cultural platforms. This helped with comparatively better economic stability as Tholppavakkooth got more stages across India and abroad and was accepted as a form of applied theatre.

Their endeavour was further invigorated by Ramachandra Pulavar as he dealt with many non-religious texts as the literature for tTholppavakkooth. This eventually culminated in the emancipation of women puppetry artists as they were encouraged to come forward with an all women puppetry team which is indeed a historical move that challenged the conservative norms that restricted women’s artistry.

2 Comments

wow… women power…

come forward to the development of indian cultural arts..

congrats..

ഒരുപാടു വേദികൾ ഇനിയും ലഭിക്കുമാറാകട്ടെ. ഈ സ്ത്രീകൂട്ടായ്മക്ക് എന്റെ എല്ലാവിധ ആശംസകളും. എവിടെയാണോ സ്ത്രീ ആദ്ധരിക്കപ്പെടുന്നത് അവിടം സ്വർഗ്ഗമാകുന്നു.