How a 500-year-old string puppetry, Kalsutri Bahulya, was revived.

In Maharashtra’s Konkan region, Parshuram Gangavane, a famous folk artist, turned a simple cowshed into a museum to bring back Kalsutri Bahulya a string puppetry art form. His work not only shows how beautiful thus art form is but also teaches about its history and culture. This art has been performed by Thakar tribes around in Maharashtra for over 500 years. Legend says Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj once asked a tribe member, Vishram Gangavane, to spy for the kingdom because he knew the wandering musician visited every house in the area. Over time, the focus of Thakar artists shifted from these rare art forms. When Parshuram, Gangavane’s great-grandson, saw the art form fading away, he worked hard to save it, including making this museum in Pinguli.

Chethan Parashuram Gangavane, Parshuram’s son, explains to India Art Review about their community’s tradition of performing Kalsutri Bahulya. Chethan is an engineer and the 12th generation artist in his family. The Kalsutri Bahulya shows are now a big part of celebrations in Maharashtra. Chethan talks about how hard it was to keep their community’s art alive because there weren’t enough people willing to continue it. He thanks his father for bringing back these traditions and making a museum to show and teach them. Parshuram Gangavane got the Padma Shri award in 2021 for his efforts. Chethan says people are starting to appreciate these art forms more because of the museum and their ongoing work.

Origins of the Kalsurti

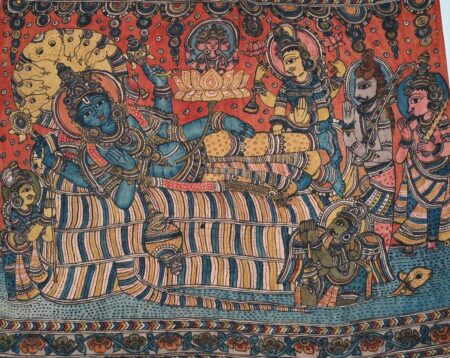

According to etymology, “Kalsutri” can be broken down into two words, “Kal” and “Sutri,” meaning “fingertip” and “string” respectively. “Bahulya” signifies the “puppet.” The puppets, crafted from wood, primarily furniture woods for durability, are fastened with strings to enable movement. The tales typically enacted are from the Ramayana and Mahabharata. Generally, the entire performance takes place within a puppetry box measuring 8 feet in length, 6 feet in height, and 4 feet in width. The box-type theater is a distinctive feature arranged to ensure visibility of the puppets even from afar.

The wooden puppets stand at approximately 1.5 feet tall and are embellished with facial colors and vibrant cotton clothing to captivate the audience. Previously, natural dyes were utilized, but now oil paints are employed for puppet faces. Chethan asserts that his family still possesses puppets nearly 300 years old that are still used in performances. The strings used to manipulate the puppets are akin to those used for repairing sandals, possessing elasticity and durability. A basic puppet typically employs three strings: one attached to the head and two for hand movements. These strings are affixed to a stick controlled by the puppeteer, with hand movements creating the necessary actions of the puppets.

“We perform the show in temples during the nine-day festival of Navratri and during Diwali. The show usually commences at night, lasting until morning, where we perform for all these days with a lengthy storyline,” Chethan remarks.

Chetan also highlights two unique puppets featured in the Ramayana: the “rakshasha” and the “rakshashi,” servants of King Ravana. In the entire Ramayana Kalsutri Bahulya, these two characters exhibit mouth movements, particularly with an angry demeanor.

The puppet show requires five to six artists to coordinate and perform the entire content. The narration, music, and dialogues are delivered in a mixed order to convey the entire story. Marathi is the language used throughout the show. Various instruments, such as the table, Manjira, Tuntuna, and Harmonium, are utilized to enhance the musical quality. A brief storyline is provided to the audience before the performance to reduce language barriers, and during the show, brief narrations, songs, and dialogues, along with puppet movements, convey the intended meaning. Chethan also notes that post-program discussions have exposed them to many new art forms and cross-cultural differences, which he considers a blessing.

Behind the curtain

The performance begins with Ganesh Vandana, offering salutations to Lord Ganesha to remove all obstacles, followed by the sequential presentation of the story. The table player, known as the “Nayaki” or main artist, controls the entire stage, along with other instrumentalists seated outside the puppet box. Inside the puppet box, puppeteers, or “Sutradhars,” manipulate the puppets. Interaction between these two groups occurs without eye contact, with a curtain separating them throughout the show, a task Chetan describes as Herculean, as the entire performance depends on this interaction.

Despite numerous initiatives to support the art form, youth show limited interest in it. Chetan laments that many students gravitate toward metropolitan cities without attempting to learn or appreciate the importance of their community’s art forms. Another challenge, according to him, is scripting new stories. He expresses, “I love creating new stories. However, the art form itself is traditional, limiting our ability to incorporate new narratives, as we must create puppets according to the storyline.” Additionally, adapting stories into languages other than Marathi poses difficulties. Chetan believes that artists can express content most fully and genuinely in their mother tongue, making it challenging to break out of that comfort zone. Nonetheless, they have produced puppetry adaptations of Panchatantra stories in English for children and other awareness campaigns in collaboration with government schemes.

Chetan’s plea to future generations and those inviting them for performances is simple: “Please provide us with a proper stage, as this is an art form, not merely a street play. The art form possesses its own purity, so please help us preserve it. To the younger generation, I urge you to reconnect with your roots at some point in your life to maintain a sense of belonging.”