Blending organic farming with rural theatre, Sreeja Arangottukara and CM Narayanan carve out an offbeat culture career.

The paddy field bordering the open backyard of the couple’s mud-house is maturing yet again. Typically, next month’s harvest overlaps with a cultural festival helmed by KV Sreeja and CM Narayanan. This time, though, Covid-19 will vane the annual event. That no way makes the husband and wife gloomy. Far from it, they are busy as usual, dividing time between agriculture and culture. Organic farming and rural theatre, to be specific.

A quest for blending the two domains led middle-aged Sreeja and Narayanan to found a sociocultural movement in their green and rugged village in central Kerala. Thus was formed Patasala — in 2005, at Arangottukara in the cusp of Thrissur and Palakkad districts.

As the institution began to make a mark on Kerala’s heritage map, Patasala found the resources to launch ‘Koithulsavam’ (harvest festival). and has been a multi-art celebration in Januaries, coinciding with the crop-yield during the Malayalam month of Makaram.

The open-air Koithulsavam has gone on to become a many-layered event spanning two days or even three. The festival tends to bring together the spirit of two major activities of mankind, appearing as a vegetable and food-grains fair even while entertaining programmes on performing arts, cinema and literature involving personalities from places outside Kerala as well.

Minimalist theatre

Cut to Idanilangal, a play conceived and written by Sreeja in 2007. She performs a key role in it, acting opposite Narayanan, who is the director. The 45-minute production has by far found 200 stages across the length and breadth of the state. The turn of the present century was when people began to realise the ill-effects of fertilisers and pesticides in farming, recalls Sreeja, who works in a government office at Pattambi town, eight km north of her residence. A new wave of understanding about the long-run benefits of agriculture that retains conventional values began prompting a few to experiment with age-old sowing-and-growing techniques in the new world.

Idanilangal (Transit Camps), with five characters, portrays the peril of a farmer keen to sell off his land that can pocket him quick money easily. “The work,” notes Narayanan, “has that way had its natural evolution from farmland to the dais, so to speak.”

The play’s canvas of farming includes dairying as well. It’s something Sreeja and Narayanan practise in real life, just as they do organic farming and inspire residents in their locality and far. The couple maintains a stable housing two dozen cows belonging to breeds that are endemic to Kerala.

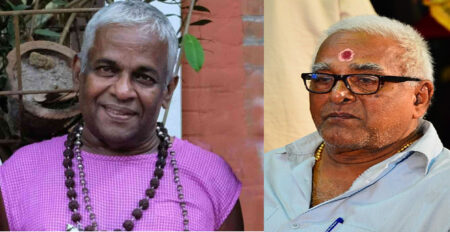

Artist-writer V Gireesh notes that Idanilangal portrays a sad slide in the values held by a family once the members distance from their traditional association with the primary sector of the economy. “It takes a minimalist approach. With no special lighting or audio effects, the play plainly essays the goings-on inside a house — with all the intended results,” he says. Actor-activist VK Sreeraman observes that the rural play highlights an increasing grip of land mafia in Kerala and the resultant exploitation of peasants. “Natural resources are for us to share, not establish a monopoly,” he adds.

Course forward

Sreeja and Narayanan are alumni of the Government Sanskrit College in Pattambi of Palakkad district. Her graduation days at the institution drew Sreeja towards theatre, which Narayanan had already made his passion. They married in 1994. Two years later, Sreeja got employed in the state’s sales tax department.

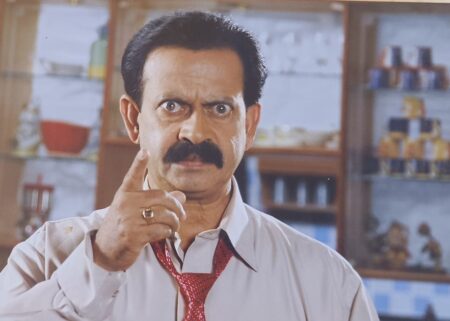

Narayanan was initially into children’s theatre. “I used to script the plays, and direct them too,” he says. Then, in 1997, Sreeja made an unanticipated entry into acting, having had to act in a play based on Koottukrishi — a poem by late Edasseri Govindan Nair. That was in neighbouring Malappuram district’s Ponnani, a bustling seaside town which gave birth to several litterateurs and artists in the 20th century.

Into its last decade, the state witnessed a particularly infamous criminal case that involved the abduction and subsequent rape of a teenaged schoolgirl from Suryanelli in hilly Idukki district. The horrific 1996 incidents that unveiled down the investigations prompted Sreeja to pen a play. The resultant Ororo Kalangalilum was well received, more so owing to its thematic linking with the patriarchal 1905 Smarthavicharam trial of a young Thathri Kutty, a Namboodiri female alleged to have slept with several men amid a troubled marriage.

Patasala went on to stage several plays with a social message. They included Labour Room, Kalyana Sari, Ithiri Poovil and Urvara Sangeetham. Some of them saw the participation of workers of the state’s Kudumbasree women empowerment project and support by the pro-Left Purogamana Kala Sahitya Sangham.

Kathakali dancer and theatre actor Peesappilly Rajeevan points out that Patasala, which also organises summer camps for schoolchildren, eminently proves its practicality in a basically romantic world that is art. “The work by Sreeja and Narayanan during the present crisis triggered by the pandemic is the latest instance to it,” he adds.

As for Koithulsavam 2021, the event in January will be relatively less colourful. “But, we won’t skip it,” says Sreeja.