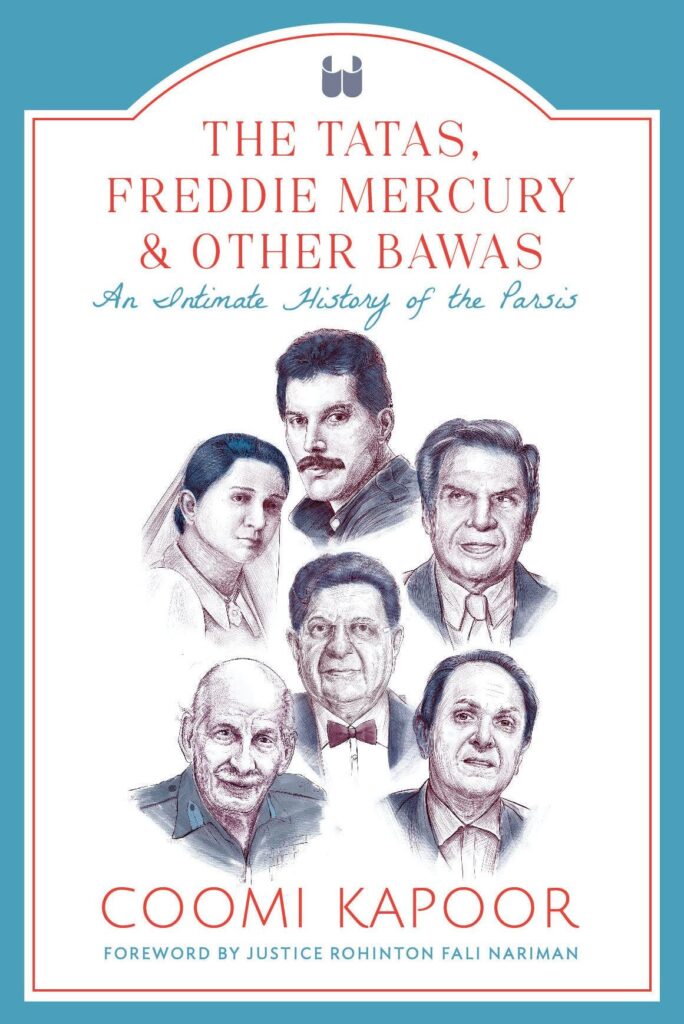

Excerpt from Coomi Kapoor’s book The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas on the role of Parsi championing women’s rights in India.

Bhikhaiji Cama, who is discussed in greater detail in a later chapter, is probably the best-known Parsi woman and exemplified two important characteristics seen in many Parsi women: empowerment and a deep social conscience. But even before Bhikhaiji, Parsi women occupied important roles within their families and were not restricted to domestic chores. Some of the women in the Wadia and Readymoney families, for instance, helped run the family businesses. Bhikhaiji played a major role in the freedom struggle, but she was not the only one. True, the revolutionary instinct of many Parsi women was snuffed out by their families whenever possible. Dhanbai Petit, for instance, came down to breakfast in a khadi sari, only to be ordered by her mother, Maneckbai, to go back and change. Maneckbai told her daughter that the Petits were a family loyal to the king and that if Dhanbai wanted to follow Gandhi, she might think about leaving home and moving to his ashram. Dhanbai obediently went upstairs and changed.

But another aristocratic Petit girl, Mithuben, defied her family rather than renounce her principles. The daughter of Sir Dinshaw Petit, Mithuben had followed Mahatma Gandhi since his return from South Africa. She stood behind Gandhi-ji at Dandi (then Navsari) on 6 April 1930 when he broke the British Raj’s salt laws. (Mithuben is one of the main figures in Deviprasad Roychowdhury’s iconic sculpture in Delhi depicting the march to Dandi.) Two years earlier, she participated in a campaign headed by Sardar Patel against taxes imposed by the British. Mithuben took up social work fulltime and opened an ashram in Maroli, Gujarat, for poor tribal and scheduled caste children. She taught them useful skills, from handling sewing machines to leather work and dairy farming. She also opened a hospital for the mentally ill.

Progressive Parsi women can take the credit for breaking many glass ceilings for Indian women. Cornelia Sorabji, who came from a Parsi family that converted to Christianity, was the first woman to graduate from Bombay University, passing the exams with flying colours. She went on to study law at Oxford University in 1892; in those days, Oxford did not grant women degrees, so when she returned to India, Cornelia did her LLB from Bombay University. It took until 1923 for her to be admitted to the Bar after the law was changed to allow women to enter the profession. She practiced in the Allahabad High Court, but she worked mostly with purdahnashins, women who observed purdah and as a result were ignorant of their legal rights in India, including their shares in the estates of fathers and husbands who had died. She wrote several books on her experiences and two autobiographies.

Book Details:

The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas: An Intimate History of the Parsis

By Coomi Kapoor

Westland Non-fiction

Pages: 320

Price: Rs 256

Publishing Date: 12 July 2021

Technically, though, the honour of being the first Indian woman barrister goes to another Parsi, Mithan Jamshed Lam (née Tata), who studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, London, when women had just begun to be permitted to practise as barristers. In fact, in 1923, Mithan had the distinction of being the first woman ever called to the Bar from Lincoln’s Inn, as well as the first Indian woman to be called to the Bar in Britain.

Mithan’s interest in law was aroused because of her championship of the suffragette movement. She and her mother Herabai Tata, while on a holiday in Kashmir in 1911, had a chance encounter with Sophie Duleep Singh, a feminist who proudly flaunted the badge ‘Votes for Women’. Both Mithan and her mother were drawn to the cause, despite reservations from some in the freedom movement who felt that fighting for independence from colonial rule should be the priority. The struggle for gender equality should in the meanwhile take a backseat. Mithan saw no contradiction between the two demands. ‘Men say Home Rule is our birthright. We say the right to vote is our birthright and we want it,’ she declared in 1918, paraphrasing Gandhi-ji’s famous words. Mithan and her mother were selected by women’s groups in Bombay to represent their view before the British parliament, which was considering a package of reforms later to become known as the Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms. While unsuccessful in the immediate goal, the British parliament did leave the issue to the discretion of individual Indian provinces. In 1921, both Madras and Bombay presidencies granted limited women’s franchise.

While in London to plead the women’s cause, Mithan also pursued a legal education and a master’s degree in economics from the London School of Economics. When she returned to India, she found herself the sole female lawyer in the all-male Bombay High Court. ‘I felt like a new animal in the zoo,’ she recalled. According to court lore, she got her first case because the client had instructed the solicitor to engage the only woman lawyer as it would be a double humiliation for his opponent when he lost. However, she soon built up a formidable reputation on the strength of her legal skills. Her cases ranged from prosecuting currency counterfeiters to defending the validity of a Jewish betrothal.

(Excerpted with permission from The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas: An Intimate History of the Parsis by Coomi Kapoor, published by Westland Non-fiction)

Write to us at [email protected]