Agatha Christie might hold the record as the world’s best-selling fiction writer, but the author was disappointed by the first novel of hers he chanced upon at the age of 14. But he didn’t give up, and considers Christie unparalleled in cleverly deceiving the reader.

I was first introduced to the works of Agatha Christie when I was around 10 years old. On a visit to my mother’s ancestral home at Irinjalakuda during the summer holidays, I was rummaging happily through the books in my cousin’s and uncle’s collections. My cousin’s collection consisted of several bound volumes of comics and a stack of novels by James Hadley Chase, the only author he read. I had already read the comics several times over. Chase was an author I was not into at the time, primarily because I disliked the covers on the Corgi editions that my cousin possessed. My uncle’s collection was the one that introduced me to a host of wonderful writers from different genres. It was here that I met the likes of Mickey Spillane, Erle Stanley Gardner, John Dickson Carr, Edgar Wallace, Leslie Charteris, John Creasey and several others, all crammed into a small 4*3 ft cupboard in his bedroom. I was making the transition from comics to novels at the time and these volumes were like manna from heaven. I went through most of them like a hot knife through butter.

What else could you expect from a writer named Agatha?

That is when I chanced upon a book by Agatha Christie. It was a Dell edition of her book Dead Man’s Folly. The title intrigued me and I picked it up and started reading. To say that it was a disappointment would be an understatement. I was used to tall, handsome and tough heroes like Simon Templar (The Saint), Mike Hammer, Inspector Roger West and others of their ilk. The main character in this one was a short, rotund, egg-headed little Belgian with a waxed moustache who went by the improbable name of Hercule Poirot.

The story meandered on and there were no shootouts or punch ups at all. What else could you expect from a writer named Agatha? I pictured her as a clone of Bertie Wooster’s dreaded Aunt Agatha in the Wodehouse novels, the dried-up shrew who ate ground glass for breakfast and could stop a charging wild elephant dead in its tracks with a glare through her lorgnette. I quit halfway through, thoroughly bored, and returned happily to Mike Hammer dealing out justice with his trusty .45 pistol. To be frank, even when I finally reread and completed Christie’s books years later, I felt Dead Man’s Folly was one of her weakest.

A few years later when I was around 14 and had exhausted most of the books in the school library, I again picked up an Agatha Christie novel. This one was called After the Funeral (American title Funerals are Fatal). This time around I found that the plot drew me in though there was still no action. Christie was the master of the cosy mystery where characters with stiff upper lips hardly showed any emotion and murders were considered par for the course, nothing to make a fuss about. You would have a situation in which the butler would announce to the lady of the house that tea would be served in the garden instead of the library because His Lordship had been stabbed and his body was now draped across the tea table.

Her Ladyship would not bat an eyelid but would tell Travers (butlers are always called Travers or Smithers or Baxter or Murgatroyd or Jeeves as the case may be, but never Smith, Jones or Brown) something on the lines of ‘I wish he’d been more considerate and not get stabbed on the tea table just before teatime. Call the police after 10 minutes so that the guests can have their tea in peace and do ensure that His Lordship’s blood has not splashed on the priceless leather-bound set of Walter Scott’s books.’ You get the idea, I am sure.

Where brains, and not brawn, rule

I found the book refreshing, after my usual diet of blood and gore and severed limbs. Even the pompous little Poirot was a welcome change after the bloodthirsty Mike Hammer, Parker and other macho heroes. The book was absorbing and I had a tough time stopping myself from turning to the last few pages to discover who the murderer was. The objective of the mystery writers of the golden age of mystery writing (from the 1930s to the 1950s) was to deceive the reader while being fair and providing all the clues.

The success of the writer was in concocting a plot where the least likely character turns out to be the murderer and Christie had this ability in spades. I certainly could not figure out who the murderer in After the Funeral was, and the revelation came as a surprise. She had provided all the clues but I had not guessed correctly. The final denouement has the little Belgian calling all the main characters for a discussion (as was the norm in most golden age mysteries) to explain the circumstances of the case before unmasking the murderer with a theatrical flourish. I loved the book and even began to admire the little detective. Being able to shoot four people in a second or battering five toughies without breaking a sweat was all very well but you have to admire a person who uses his ‘little grey cells.’ Brains and not brawn were what Poirot used and I began to identify with him because I was short on brawn myself though modesty forbids my drawing a comparison with his brains.

Miss Marple could give Poirot a run for his money

I now started on a quest to read all the books by Christie. These were very easy to find as my school library had a number of them as did the British Council Library and the Trivandrum Public Library. Within a year I had read most of her prodigious output and enjoyed every one of them. I discovered and fell in love with her other major series featuring detective Miss Jane Marple, the frail and gentle little spinster from the village of St. Marys Mead with a razor-sharp brain. Miss Marple could even give Poirot a run for his money. Her knowledge of human nature was second to none, all gleaned from various incidents in the quaint village she resided in. Reading Christie, one would think that the number of murders that occur in quaint English villages and country houses would be about ten times those in the underworld in America, France and Germany combined.

The unparalleled David Suchet as Poirot on TV

Both Poirot and Miss Marple have featured in fabulous television adaptations. ITV produced the wonderful series Poirot, starring the magnificent David Suchet as the definitive Hercule Poirot, with Hugh Fraser as his Watson and friend Capt. Hastings, Philip Jackson as the hapless Inspector Japp and Pauline Moran as his secretary Miss Lemon. It would be fair to say that all these actors will forever be associated with these characters even though they have played several other roles in their long careers. The series lasted from 1989 to 2013 and is a must-see. Subsequent adaptations have all paled in comparison to this one and though several great actors including Peter Ustinov and John Malkovich have played Poirot on TV and in films, none have matched up to David Suchet.

The BBC broadcast a series called Miss Marple from 1984 to 1992 based on the Miss Marple novels with Joan Hickson living the character of the detective just as you would visualise her while reading the novels. Another series called Agatha Christie’s Marple was broadcast by Granada from 2004 to 2014 with Geraldine McEwan and later Julia McKenzie playing Miss Marple. Miss Marple was also portrayed on TV and in films by thespians such as Helen Hayes, Margaret Rutherford and Angela Lansbury, but I would always recommend Joan Hickson’s series above all others.

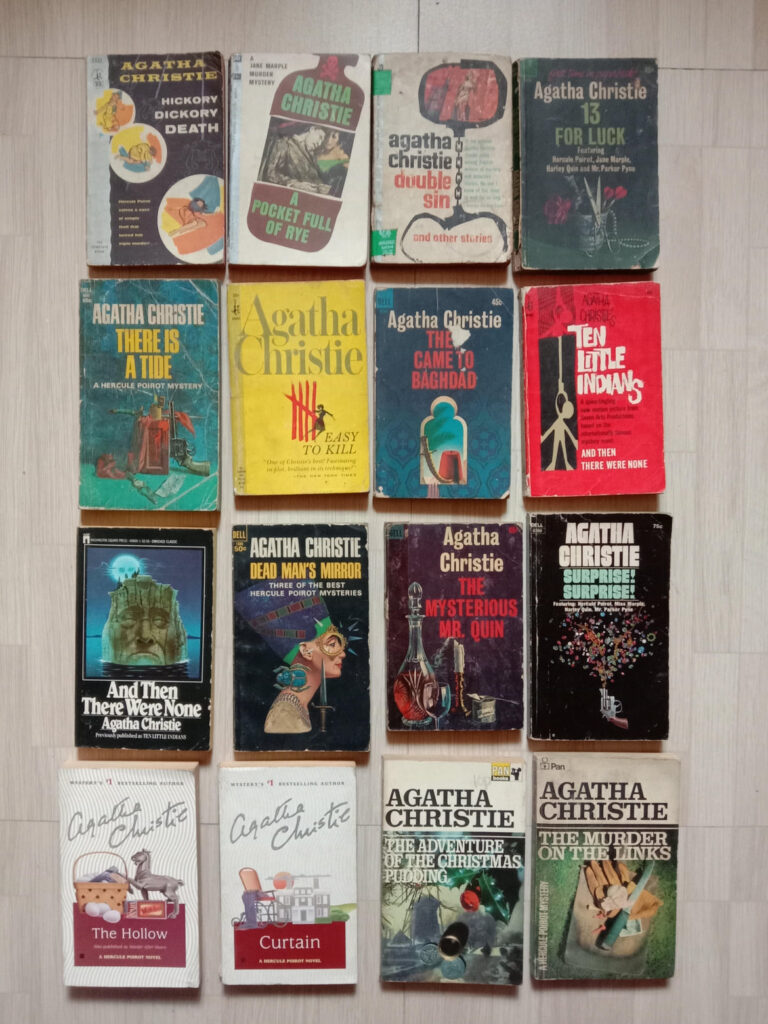

56 years, 80 books

Christie was a solid and workmanlike writer though she lacked style and her characters were often pasteboard. Her forte was the plot and in my opinion, she remains unsurpassed for the sheer diversity and magnificence of her plots. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, The Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, A Murder is Announced and Ten Little Niggers were just some of her books with plot elements that had never been done before. Over a long writing career that encompassed 56 years and 80 books, she never failed to entertain, enthral and mystify her legions of fans. Apart from the Poirot and Marple novels, she also wrote a series about Tommy and Tuppence Beresford which was also adapted for television as Partners in Crime. She wrote several standalone mysteries and her early works were mostly light-hearted thrillers typical of the novels of the 1920s.

She was a master of the short story format as well and wrote several collections featuring Poirot and Marple among others, plus a few terrific stories with supernatural elements in two of my favourite collections of short stories — The Hound of Death and The Mysterious Mr Quin. Her play The Mousetrap is the longest-running play ever and was performed on stage at the West End from 1952-2020, an unbroken run of 68 years. Witness for the Prosecution was another Christie play that was hugely successful and was later filmed in 1957, with Tyrone Power, Marlene Dietrich and Charles Laughton in the lead roles. It was also the basis for a television mini-series in 2016. It received the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award for Best Play in 1954. Christie wrote romances under the pseudonym, Mary Westmacott, though these were never as successful as her detective novels. She was bestowed the honour of DBE (Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1971 while the Guinness Book of Records credits her as the world’s bestselling writer, selling over two billion copies of her books.

The legacy lives on

The Golden Age threw up several brilliant women mystery writers including the four dubbed the Queens of Crime – Agatha Christie, Margery Allingham, Dorothy Sayers and Ngaio Marsh. There were several other terrific women writers during this period including Josephine Tey, Gladys Mitchell, Christianna Brand, Patricia Wentworth and Anthony Gilbert (yes, she’s a woman!). During the latter half of the 20th century, a new crop of fine women mystery writers took the centre stage including Ruth Rendell, PD James, Elizabeth George and, my personal favourite, Joyce Porter. However, whenever the term Queens of Crime crops up, the first name that will spring to mind, and rightly so, is Agatha Christie. Christie passed away in 1976 but her legacy lives on. Her books are never out of print and continue to delight the new generations. The Queen is dead, long live the Queen.

Read Shelf Life on Enid Blyton