Birju Maharaj’s meticulous practice involved memorising nuances through mirrored observation, ensuring perfect angles, and practicing relentlessly, even in his twilight years.

Birju Maharaj would have turned 86 today(February 4). As usual, his birthday is marked with the ongoing celebration of the 26th annual Vasantotsava festival. This year, for the first time, an award has been instituted in his name, which will be presented to tabla maestro Ustad Zakir Hussain. Interestingly, such was the relationship between the two maestros; Ustad Zakir Hussain is coming to receive the award and the next day flying back to the US for the Grammy awards.

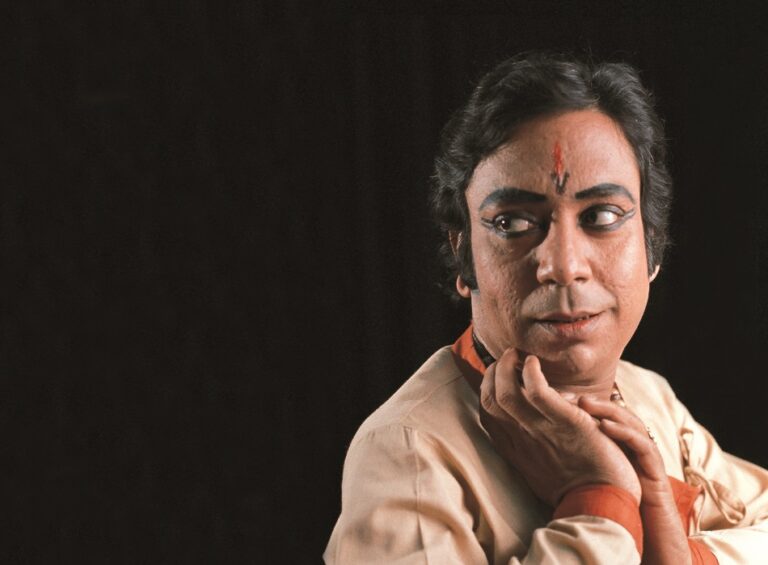

More than anyone else in living memory, Pt Birju Maharaj gave Kathak a legitimacy and status that it didn’t have.

Of course, Kathak has a proven antiquity as a classical dance form. The State Museum in Patna has a beautiful 3D sculpture of around 2000 years ago, of a pirouetting dancer, with her billowing dress – according to dancer Shovana Narayan, this is undeniable proof. She also referred to an inscription from Mauryan times about “kathak.” But, to the uninitiated, Kathak represented the dance form of the courtesan. Until recently, films made for North Indian audiences usually depicted Bharatanatyam for any visuals of classical dance; Kathak was depicted for the “mujra” scenes!

This perception persisted until the era of Birju Maharaj, whose mastery gradually reshaped the public’s view of Kathak. His name became synonymous with the dance form, and it was believed that there wasn’t a Kathak dancer worldwide, regardless of their “gharana” (school), who wasn’t influenced by Birju Maharaj. Over time, he taught several hundred students from around the globe, engaging in dancing, choreographing dance dramas, and contributing to films and TV shows, solidifying his position as the undisputed King of the genre.

Accolades poured in; he received the Sangeet Natak Akademi award at the remarkably young age of 26. Incidentally, he became the youngest dancer ever to be honored with the Padma Vibhushan at 48, the third dancer to achieve this, following in the footsteps of Uday Shankar and Balasaraswati.

Much has been discussed about his lineage; he belonged to a family of dancers, singers, and tabla players, with one branch establishing the Banaras gharana of tabla. Born as Brij Mohan Mishra on February 4th, 1938, in Lucknow, Birju Maharaj faced the challenge of continuing his craft after his father and Guru passed away when he was only nine. He had to learn from his uncles and through observation, without the luxury of a Godfather passing down the stage in “virasat”; he had to earn his place. However, even at that tender age, his undeniable inherent talent was evident; Maharaj recalled his father once saying, “ye to mera baap aa pauncha hai” (he has surpassed me).

Connecting with the audience

Dancing as a child in the court of Rampur, Birju Maharaj grasped the esoteric link between performer and audience from an early age, understanding that communicating the art surpassed virtuosity. Arguably, he was the most effective communicator of art in his time, using every means at his disposal to convey his artistic vision. No wonder he could instantly connect with any audience worldwide.

An incident in Jhansi over 60 years ago beautifully illustrates this; faced with a vocal and disenchanted audience, Birju Maharaj improvised on a “paran” (composition) whose “bols” sounded like a galloping horse, intertwining it with the tale of the Rani of Jhansi’s valor on a horse. The cynical audience was completely enthralled, and he performed for an hour and a half!

The sense of proportion, knowing when to stop, is something all great performers instinctively possess; with Birju Maharaj, this intuitive “feel” transcended the physical. He frequently changed his act, even mid-performance.

Concept of four key movements

Dance scholar Dr. Arshiya Sethi, in an interview with the legend, highlighted a crucial aspect of his legacy: the creation of a terminology for movements used in Kathak. The maestro humbly acknowledged that his innate focus on every aspect of movement was integral to him. He emphasized the importance of thorough and complete learning, drawing parallels to musicians who asserted that mastering a few ragas inside out allows absorption of countless others. In the context of dance, he emphasized the significance of understanding four key movements – the use of the wrist, elbow, shoulder, and chest – stating that mastery of these movements completes a dancer’s expressive repertoire.

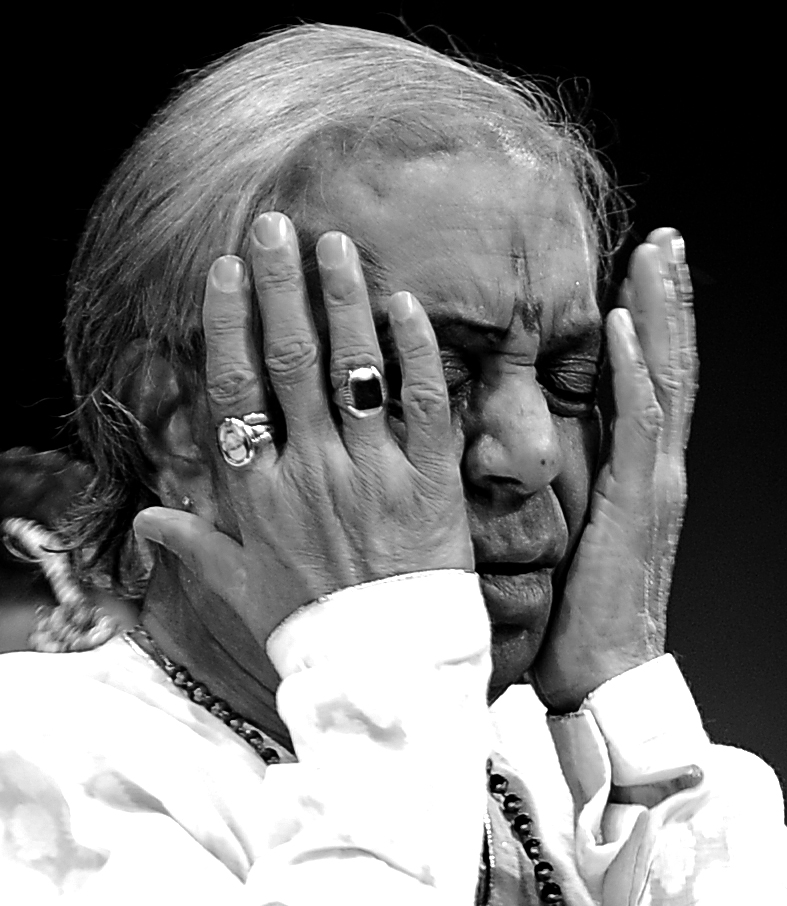

This intense focus remained a lifelong obsession for Birju Maharaj. His meticulous technique, such as using a mirror to observe and memorize the exact angles of his movements, reflected an intense love for the craft and a commitment to detail. Despite ailments and age, he expressed his sense of incompleteness unless he formally presented himself, even if only for a few minutes daily.

Birju Maharaj’s influence extended beyond his personal practice. He introduced changes to the presentation format of Kathak, now considered the norm. Additionally, he expanded the Kathak repertoire on an incredible scale. His holistic approach to art, combining visual, aural, and emotional dimensions, resonated in his belief that a dancer should be someone who can look in all four directions.

Beyond dance, Birju Maharaj demonstrated versatility as a painter, erudite musician, lyricist, and instrumentalist. His self-taught mastery of the sarod, considered one of the most challenging instruments, showcased his relentless pursuit of artistic excellence.

His poetic sensibility found expression in copious poetry, reflecting his deep devotion to his “isht” Shri Krishna. His unparalleled “bhaava” (abhinaya) and mastery of “laya” and rhythm contributed to his status as a supreme aesthete. From childhood, he analyzed and dissected the art of his father and uncles, constantly seeking beauty in every action.

As a confident artist, Birju Maharaj engaged in collaborations spanning over 50 years with artists from various genres.

Notable jugalbandis included those with Odissi maestro Kelucharan Mohapatra, renowned for his “abhinaya.” Collaborations with artists like Kishori Amonkar, Dr. L Subramaniam, Shobha Gurtu, Padma Subrahmanyam, and a younger generation of musicians showcased his adaptability and continued artistic exploration.

Recalling a dashing performance in Varanasi’s Sankat Mochan temple, where Birju Maharaj depicted a peacock without moving his feet, exemplified his ability to transport audiences with effortless grace. His belief that “dance makes you beautiful” resonated on stage, where Padma Vibhushan Pt. Birju Maharaj ji stood as the epitome of beauty.

1 Comment

Thoroughly enjoyed reading this touching, informative and inspiring piece.