Six books by Dr. Seuss have been taken out of publication citing the racist and insensitive drawings in them. History shows children’s books are infested with all the human biases and prejudices. It’s an Aegean stable and clean-up isn’t easy.

ids love Dr. Seuss. Theodor Seuss Geisel (1904-1991) is the author of more than five dozen books under the pseudonym Dr. Seuss. Most of his works, such as Green Eggs and Ham and Cat in the Hat, are immensely popular among children across the globe. The American author has already sold nearly 650 million copies and has been translated into more than 30 languages. But on March 2, on the birth anniversary of Geisel and just two days before the World Book Day, Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the trust that manages the author-animator’s iconic books, decided to pull from publication six books as it felt the books “portray people in ways that are hurtful and wrong.”

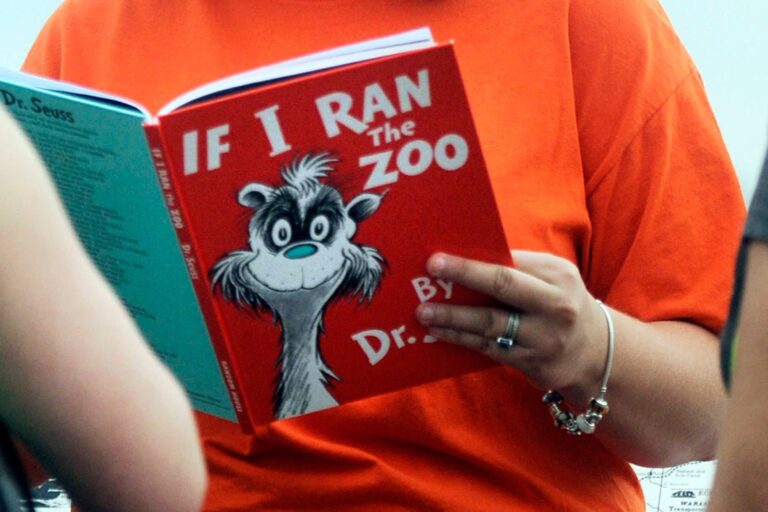

According to Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the withdrawn books include And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, If I Ran the Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super! and The Cat’s Quizzer and were originally published between 1937 and 1976. Bibliophiles, historians and rights activists have for years criticised these books for the way they caricatured Asians and Blacks and provided their very young reader with the wrong ideas of stereotyping and racist ridicule.

For Dr. Seuss Enterprises, the decision to withdraw six popular titles would cost good money. Still, the organisation felt it should give the works an audit that’s in sync with the ethos of the times and set an example for the rest of the publishing world. Dr. Seuss’ books are represented by publishing biggies such as Random House and Vanguard Press. The company feels ceasing sales of these books will help make its catalogue more inclusive and race-sensitive.

Racism in children’s literature

Today, there is some consensus among readers, critics and publishers that many of the blockbuster titles from blockbuster authors such as Roald Dahl are laden with racist, sexist and inappropriate remarks and they are going to groom young readers the wrong way. For instance, an interesting analysis by US academic Lindsay Pérez Huber shows in 2015 the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, a research library that tracks the publication of children’s books, received 3,200 children’s books and a little only 85 had Latinx characters. Juxtapose this share (2.5 per cent of the total) with the fact that Latinx children represented about 1 in 4 school children in the US, you’ll get the real picture, notes Pérez Huber.

Several books stereotype people of colour and different, non-white ethnicities (mainly Blacks, Asians, Hispanics, aboriginals, etc.). If you are a parent who loves reading books to your children you’d have by now noticed the sheer dearth of books with Black heroes and superheroes. If you are living in Asia, it is virtually impossible to get hold of books with Black characters and wherever you come across them, the characters are not presented in the right shade. Almost all the loveable characters in children’s literature, from Peter Pan to Little Red Riding Hood are predominantly white. Worse, most baddies carry the traits of non-white people, especially Blacks, Arabs and Asians.

Clearly, misrepresentations galore in children’s literature. It is really shocking that parents and pundits gave scant regard for the fact that a child in, say, the 1960s who grew up reading The Five Chinese Brothers, where she encounters five identical brothers with “slits for eyes” (peppered with images with watercolour strokes of yellow), is more likely to become a racist person in her adult ages than one who doesn’t read such a book in her grooming years.

What needs to be done?

Diversity was disastrously absent from many of those works and evidently, the children paid a price. Today, thanks to the growing awareness around political correctness and the need to groom children in politically and racially correct ways, many classics are being audited for gender, racial and ethnic biases. For instance, today, the term ‘White Man’s Burden’, coined by Rudyard Kipling, to denote the moral duty of the white people to “civilize” other races, is seen today as an imperialist idea. In schools, such phrases are dealt with deserving criticism.

Still, critics say children’s literature is still infested with racial, gender and ethnic biases and in the age of digital technology-powered distribution networks, which have improved access to children’s book better than ever, it is important to screen the content in children’s classics and re-edit them to suit to the new and emerging regimes of correctness. Those that cannot do justice to the sensibilities of the times should be chucked forever, say experts.

This is important because the child being “the father to the man” as William Wordsworth observed, biases catching them young can be dangerous to the collective wellbeing of societies, say sociologists. Children groomed in supremacist ideas courtesy of the books they read can grow up into adults who harbour far-right ideologies. So, obviously, offering the future citizens a reading environment of political neutrality, correctness and scientific temper goes in the interest of society.

We must make efforts

That said, such efforts are not easy. For instance, in many books, there are no direct examples of racism. For instance, The Story of Babar by Jean De Brunhoff. The 1933 classic tells the story of a young “elephant” who leaves the forest for the city. He gets “education” by “humans” and soon he develops a taste for “fine clothing”. On his return, the members of the jungle anoint him as the King of the elephants and he brings a Western “civilization” to his kingdom. Sociologists have later criticised the book as a distinct attempt to glorify French colonialism.

It takes an enormous amount of patience and collective will to trace and weed out biases in children’s literature and it cannot be left to the mercy of publishers, say those who study such trends. Initiatives such as the Social Justice Books which is inspired by the 1965 organisation of Council on Interracial Books for Children (CIBC) are steps in the right direction and the models can be emulated across the globe. The CIBC aims to promote “literature for children that better reflects the realities of a multicultural society.” Interestingly, the CIBC was formed after a bunch of Mississippi Freedom School teachers raised concerns over the way African-Americans were depicted in school textbooks.

Today, there are many guides available for identifying biased content in children’s literature. Parents, teachers and librarians are not sensitised and educated to spot racism and gender biases in the books children read. The functional solutions offered by agencies such as CIBC include scrutiny of illustrations, storylines, lifestyles described in the books, how relationships between characters are depicted, how heroes are portrayed, how the reader (child) is connecting the book to his or her self image, the ethnic and social background of the author and publisher, and more. Many find these suggestions useful.

So, next time when your child reads Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and you come across the Oompa Loompas who are the happy slaves of African pygmies, a frown should visit you for good. Or, closer home in India when you see your children laugh and mock Arab-looking villains in a, say, Chhota Bheem comic or animation, and alarm bells ring in your mind, that’s a good start.