The author first took up an Enid Blyton book grudgingly, but was so caught up that he went on to read almost all her various series and was soon hooked firmly on to reading. Despite having outgrown Blyton, he still occasionally rereads an adventure story, just for the ‘unalloyed enjoyment’ of it.

The railway station bookshop, the treasure trove of comics

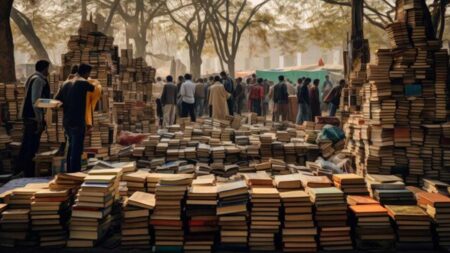

I started reading comics at the age of six or so, starting with Times of India group’s Indrajal Comics featuring the Adventures of The Phantom and Mandrake the Magician. Soon I graduated to Gold Key and Harvey comics and was soon an addict, losing myself happily in the worlds of Tarzan of the Apes, Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge, Mickey Mouse, Turok: Son of Stone, Casper the Good Little Ghost, Sad Sack, Dennis the Menace and a host of others. My father was posted in Mathura, which was a typically hot and dusty one-horse town in the early seventies. The most important part of the town, apart from the pilgrim centre of Vrindavan, was the Army Cantonment, which is where we lived. There were no bookshops in the town and my father used to buy me comics from the AH Wheeler kiosk at the railway station. As he had to visit the station frequently to receive visiting senior officers and dignitaries, I used to get my comics fix two or three times a month. Soon my collection of comic books crossed fifty. One day my father had to visit the station to meet a relative whose train was passing through Mathura station and this time my mother went along with him. Little did I know that a sea change in my reading preferences was about to occur.

As usual I reminded my father to get me some comic books from the station. I was waiting eagerly by the door when my parents returned. As soon as I opened the door I demanded my pound of flesh. To my shock and dismay my mother said that I was getting too old for comics and that she had got me a book instead. I was crestfallen, shocked and dismayed all in one. What did she mean by ‘too old for comics’? There was no age limit for comics. I was sure that I would be reading comics into my old age, and time has proved me right (Maybe my true calling was to become an astrologer, the successor to Nostradamus).

Enter Enid Blyton

Moreover, who would want to read those dowdy uninteresting books? Why, the damn things did not have any pictures and even the covers were drab and paled in comparison to the multicoloured marvels that adorned my comics. My mother pulled a thin book out of her bag and handed it to me. “Here,” she said, “Try this one. I am sure you’ll find it more interesting than your comics.” I took the offering with a sullen face. I wanted to turn around haughtily and walk off, discarding the book into the farthest corner with an imperious wave. However, one antagonises mothers at one’s peril. Good sense prevailed and I grabbed the book and slunk off to my favourite chair on the terrace, seething at the injustice of it all. I stole a glance at the cover, the book was a paperback written by somebody called Enid Blyton and the title was Secret Seven Adventure. The cover showed a boy and a girl standing next to a lion’s cage. My interest was piqued. I started to read the book, still unhappy that I had not got my comics but even at the age of eight I was enough of a bookworm to not be able to resist any printed matter. Two pages into the book and I was entranced, and soon lost in it. I surfaced an hour and a half later, having finished the book in one sitting and filled with a raging desire to read more about the adventures of the group of kids who called themselves The Secret Seven. My mom was right. Comics were for kids . Grown-ups like me should read books, especially books by that wonderful ‘guy’, Enid Blyton. I was determined to get more books by him.

Enid Blyton is a woman!

The next time my father was due to visit the station I was ready with my demand. I wanted a book by Enid Blyton. My mother was amused. “I told you you would like her books,” she said. I was shocked. For a moment I thought I hadn’t heard her right. “Her? You mean him.” “Enid Blyton is a woman,” my mother said with a wicked grin. I was shaken to the core. I was of the firm belief that women wrote only namby-pamby books and couldn’t believe that that wonderful, exciting adventure story had been written by a woman. Faced by this cruel truth, I wondered for a moment whether I should continue to read books written by a mere woman . However the reader in me triumphed. “Okay. It’s a pity she’s not a man but I’d like to read another Secret Seven book,” I said. I waited impatiently for my father to return. The minutes seemed like hours but he finally came home. I pounced on his briefcase and pulled out the book. For a moment I was disappointed, this didn’t appear to be a Secret Seven book. It was called The Mystery of the Disappearing Cat and it featured the adventures of yet another gang of kids who called themselves The Five Find-Outers and Dog. A few pages into the book and I had forgotten all about the Secret Seven as I avidly got to know Fatty, Larry, Daisy, Pip, Bets and Buster the dog. This book appeared to be aimed at slightly older children than the target audience of the Secret Seven books and was all the better for it. By this time I had fallen for Enid Blyton hook line and sinker, despite the fact that she was a woman.

Adventures, boarding schools, goblins and fairies

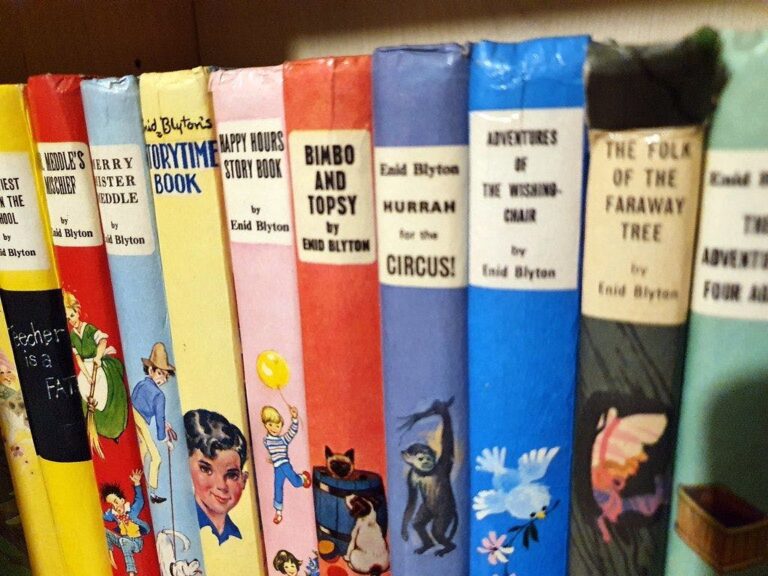

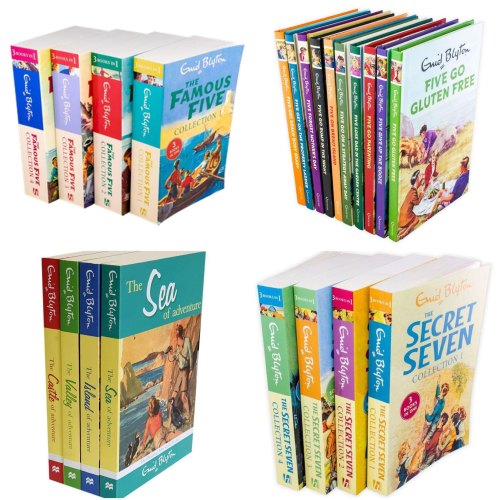

Soon I had acquired a small library of Enid Blyton books. I preferred her adventure stories with lots of mysterious goings on, dastardly villains and ineffectual grown-ups and a group of intrepid kids who would capture the villains and set things right. I had soon raced through the entire Famous Five series, the Barney adventures, The Mystery series with the Five Find-Outers, not forgetting Mr Goon the comic policeman, the Secret Seven series, the Adventure series with Kiki the Parrot , the Secret series starting with The Secret Island and several others. Enid Blyton was hugely prolific and I had lots of books to get through. I even read the entire Malory Towers and St. Clare’s series of stories set in girls’ schools, though I was careful not to let my friends know that I had read these ‘girly’ books. Once I was through these I read her other series too featuring children having everyday adventures in farms and holiday homes , more fantasy oriented stories like The Magic Faraway Tree and The Wishing Chair and her books for younger children featuring Brer Rabbit, sundry elves, goblins and fairies and even that famous nodding doll, the iconic Noddy, much before the world had heard of Barbie. My sister, the pest, had also started reading Enid Blyton books by then, and true to her contrary nature decided she liked non-adventure books like Bimbo and Topsy and The Buttercup Farm Family the most. Whenever my parents bought books for us I would try to subtly influence her to go for some adventure book I had not read but to no avail. Kid sisters are the pits.

A menagerie of pet animals

Apart from the various adventures the children in her books encountered before emerging victorious having outwitted the clumsy grown-up crooks, the most appealing factor for me were the pets the children had. Almost all the books featured a pet of one kind or another. In the late 60s and early 70s, pets were not very common in India, apart from the odd pampered Pekingese, querulous Pomeranian or surly Alsatian. Cats were not popular and many of the common dog breeds of today like Labradors, Retrievers, Spaniels, Dachshunds, pugs and the more aggressive Rottweilers, Dobermans and Pitbulls were almost non-existent in India. The fact that so many animals featured in Blyton’s books lent them enormous appeal. There was the Famous Five’s mongrel Timmy, the Five Find-Outer’s scots terrier Buster, the Secret Seven’s spaniel Scamper, Barney’s pet monkey Miranda, the aptly named spaniel Loony in the Barney series, Jack’s parrot Kiki in the adventure books and a whole menagerie of other pets that yapped, snarled, meowed, clucked, mooed and oinked through the books. You got to enjoy the experience of owning a pet vicariously, without having to undertake any of the less savoury facets of pet care in real life, and which the books were careful not to touch upon.

Scones, blackberry pies and ginger beer

The other appealing factor was the description of the food. Every book had the protagonists stopping frequently for a picnic lunch or tea. A temporary truce appeared to have been called between the kids and their antagonists and our heroes and heroines sat down to stuff their faces. All sorts of delicacies were lovingly described. One assumed they were delicacies as one had never heard of many of these sweetmeats and food items in India but they did sound enticing. Meringues, scones, blackberry pies, chocolate cake, pork pies, sardines and sausages all washed down with gallons of ginger beer. The young gluttons in Blyton’s books always seemed to be gorging and guzzling and not one of them ever came down with an upset tummy or was forced to hurriedly seek the nearest toilet while hot on the trail of the nefarious villains. Come to think of it, this was all for the best because toilets must have been in short supply on the deserted islands, hidden caves, secret tunnels, ruined old castles and other insalubrious places which appeared to be the regular haunts of these intrepid juveniles. Of course as a lifelong vegetarian I recoiled on finally getting to know the ingredients of pork pies, sausages and sardine cans. Especially sausages. Intestines filled with ground meat! Yuuccck.

Blyton for the collectors

One of the reasons why Enid Blyton’s books were so attractive to collectors was that the early editions had beautiful covers and interior illustrations. The hardcover editions from Collins, Brockhampton Press, Hodder & Stoughton and Methuen published through the 40s to the 60s were illustrated by the likes of the great Eileen Soper, Anyon Cook, Stuart Tresilian, Gilbert Dunlop, Mary Gervase and Stanley Lloyd, to mention a few. The paperbacks from Armada books and Knight books are collectable too though the illustrations of the later editions deteriorated. I feel that the Blyton books published post the late 70s are quite hideous and don’t deserve to sully one’s shelves. However Hodder Children’s Books started re-issuing the Famous Five series in the late 90s with original covers and illustrations by Eileen Soper. If you intend to collect this particular series and cannot find those lovely old editions, this is the edition you need to go for.

From Blyton to Buckeridge

Though Blyton was arguably the most popular children’s writer ever, she had to face a huge backlash from critics as in the case of most other popular writers of the period. She was called shallow, derivative, repetitive and more seriously xenophobic, jingoistic and even racist. By the 50s and 60s, librarians all over Britain started to pull her books out of libraries as they were felt to be not a good influence on children. The criticism may have a modicum of truth but Blyton was a product of the times and, in my view, should not be criticised using modern-day standards of political correctness. As my range of reading expanded I discovered other writers of juvenile fiction, who, I discovered, were even better writers than Blyton. These included the wonderful Richmal Crompton, creator of Just William series, the Jennings series by Anthony Buckeridge, Capt. WE Johns and his aviator hero Biggles, Malcolm Saville with his superb series featuring the Lone Pine Club, Willard Price with his animal collecting pair of Hal and Roger, and the greatest of them all, Frank Richards with his stories featuring the immortal Billy Bunter.

Blyton forever

However, it was eventually Enid Blyton who enticed three generations of readers into the world of books. For a writer who was first published in 1922, her books are always in print and fly off the shelves even now. I still periodically return to her books and reread them with unalloyed enjoyment, even the parts about the sausages. Blyton was the spark who lit the flame that made me an avid reader, a flame that would soon become a conflagration. A gift for which this reader will remain forever grateful.

Read the last column here