With a special allegiance to pentatonic ragas alongside Ek and Teen taals, the Patiala Gharana of north Indian classical acquires a rare ornamentation thanks to its mindboggling taans.

As a heritage-rich land, India has seen a grand passing down of several forms of art down the generations. Musical ideologies are no exception in this centuries-old process. Hindustani classical consists of various gharanas, or schools. Literally meaning ‘of the house’, each gharana has its set of distinguishing aesthetic features. They have developed through a grand link of masters and disciples. That is, the guru-shishya parampara.

Each gharana would imply a new approach to music, its interpretation or form, embellishing the existing structure. Here, every successor is a participant amid an inheritance and dissemination of ideas. Though Hindustani music has always been a niche genre, it has largely been a preserve of the elite in its native country. That is owing to its history cherished by royal patronage. Even today, amid better public awareness of the form, much of its techniques don’t gel well with modern professional requirements.

Particularly so is the Patiala gharana. As the name suggests, the school has had its origins and enrichment in upcountry Patiala. Initially sponsored by its Maharaja, the gharana was known for its thumri, ghazal and khayal styles of singing. It is, in a way, a convergence of the older gharanas of Delhi, Gwalior and Jaipur. Truly, Patiala is one of the most prominent schools of classical music from the subcontinent.

The gharana’s predominant rhythmic cycles, or taals, are Ek and Teen. When it comes to melodies, pentatonic ragas have an upper hand. The notes acquire a rare ornamentation, thanks to elaborate taans — a fast-tempo technique where the vocals gain added appeal by going for a rollercoaster ride. The manner in which notes are sung sets this gharana apart. The taans are very rhythmic and often presented with energy deriving from the naabhi (navel) instead of the throat.

Patiala taans

Take, for instance, Fateh Ali Khan. The way he emphasizes the long ‘a’ in words such as Mein lakh jatan kar is an example of the Patiala taans.

This school, predictably, has given many great musicians to the world. The royal family patronized several of them. “It was always understood that tracing one’s lineage to a major gharana was a prerequisite for obtaining a position in the royal courts,” says David Courtney, author of numerous books on the subject of Indian music. “The gharanas were entrusted with the duty of maintaining a certain standard of musicianship.”

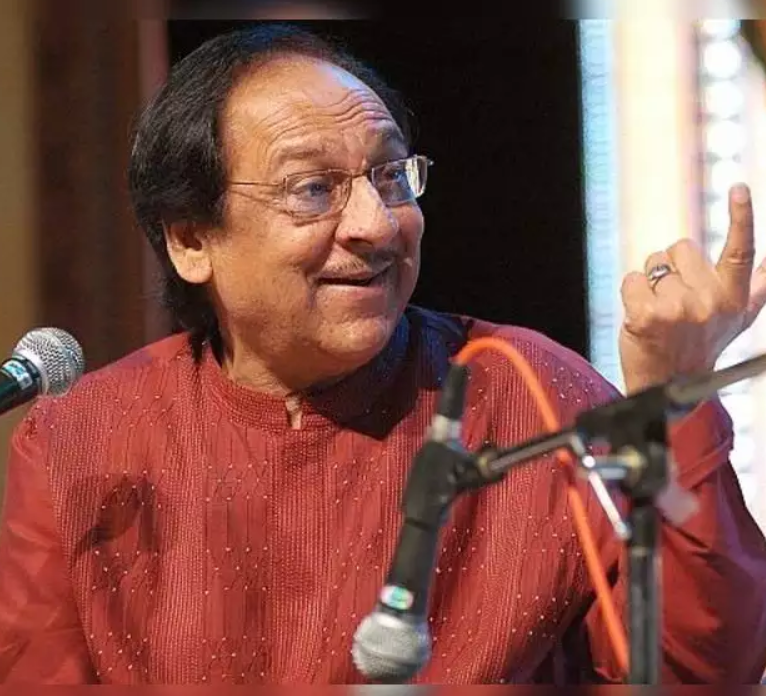

A few notable pupils of Patiala gharana are khayal musicians Bade Ghulam Ali Khan (1902-68), Malika Pukhraj (1912-2004), ghazal singer Ghulam Ali, Shafqat Amanat Ali and Raza Ali Khan.

In fact, the genius of Bade Ghulam Ali and Ali Baksh led to the creation of Patiala gharana. Peter Manuel, in his book Thumri in Historical and Stylistic Perspectives, lauds Bade Ghulam Ali’s vocal range and technique as “extraordinary”. Yet “his greatest virtue was his brilliant sense of melody and nuance; combining these assets, he was able to take thumri to expressive heights which, in the opinion of many, have not been equalled since”. The maestro was honoured with the country’s top civilian award of Padma Bhusan in 1962.

Titans and successors

The ustad’s artistry is an outcome of training under his father Ali Baksh Kasoorwaale and uncle Kale Khan (who had learned dhrupad from Behram Khan of Jaipur, khayal from Mubarak Ali of Jaipur, Tanras Khan of Delhi, and Haddu Khan of Gwalior). He blended the finest parts of Hindustani classical to give birth to a unique practice. His enthralling voice constituted romance striking a dominant note even as his trademark was exceptional emotional appeal. To this day, the gharana is identified with Bade Ghulam Ali Khan.

Patialia gharana has its singers settled in Pakistan and India since 1947. Yet this group of musicians have in common their particular style rich with distinct features. They keep the family tradition alive from both sides of the border. As Pt Shantanu Bhattacharyya, distinguished vocalist of the gharana, said, “Today’s Patiala gayaki is unmistakably the Patiala Kasoor gayaki passed on to artistes through the ganda-bandh disciples of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahib, such as Pandit Prasun Banerjee and Vidushi Meera Banerjee.”

Adds musicologist Dr Shubhada S Mandavgade: “Every performer of this category is a composer as well as an artist while performing a raga the way notes are approached in musical phrases.” What’s more, “…the mood they carry are more important than the notes themselves,” points out the associate professor, who heads the Department of Music at Sevadal Mahila Mahavidyalaya in Nagpur of Maharashtra.

It’s another matter that towards the end of the 20th century, two streams of the gharana represented the Patiala style of Khayal vocalism. One is represented by the prodigious duo, Amanat Ali and Fateh Ali. The other is by Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, Barkat Ali and Munawar Ali Khan.