On the birth anniversary of artist Ganesh Pyne who often painted what words often couldn’t say, we celebrate his legacy and contribution to the discourse of Modern Indian Art.

Born in Kolkata in 1937, Ganesh Pyne is remembered today as one of India’s most introspective and quietly potent contemporary painters. Sometimes referred to as the artist of darkness, he produced profoundly personal pictures examining death, memory, and the invisible domain always with a form of understated beauty that lingered with the spectator.

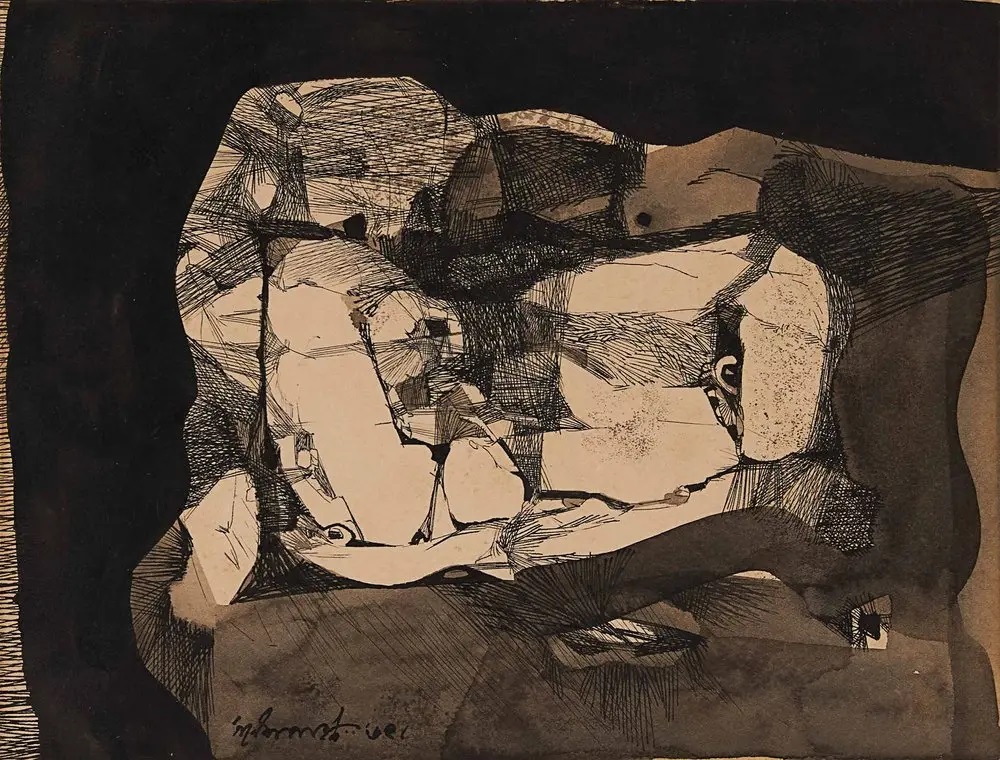

Working mostly in tempera, an old and fragile painting method that let him build his pictures slowly, in soft, radiant layers, he was often seen in a space between dream and reality. His works depict enigmatic figures, blurred memories, and understated symbols. But behind their beauty lay suffering as well.

Hardships shaped his early years; notably, the Partition violence left a profound impression on him. His art took on a darker tone as a result of these early encounters. There was light as well, though. Pyne grew up hearing his grandmother’s folk tales about gods, witchcraft, and historical heroes. These stories stuck with him and gave his subsequent work a mythical, nearly timeless feel.

A language of his own

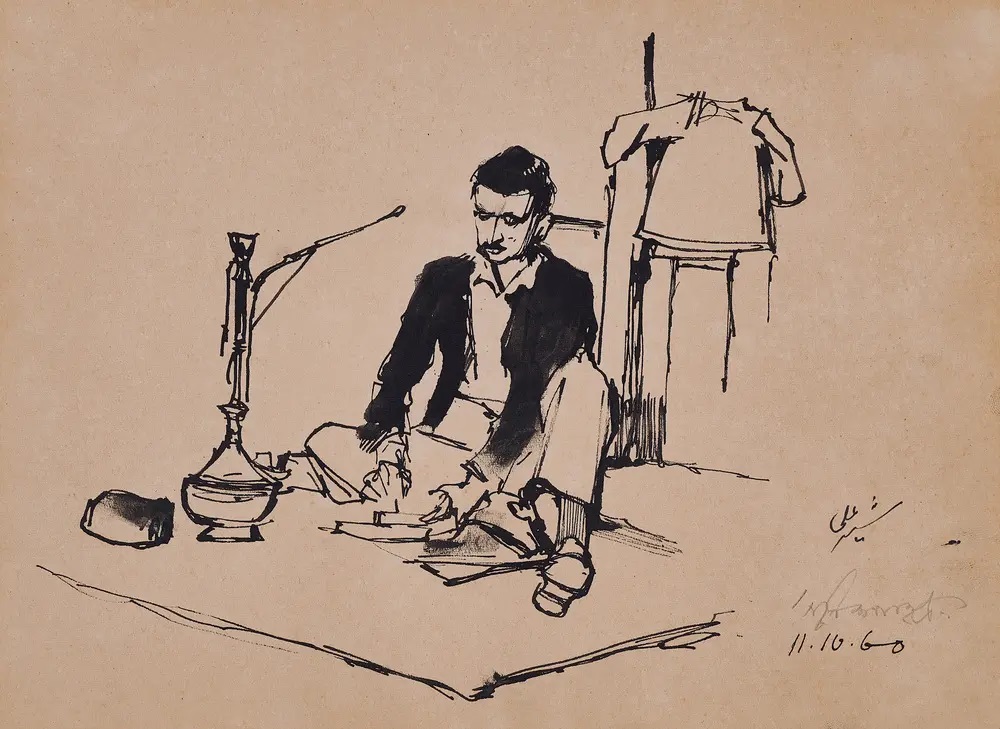

In 1959, he graduated from Kolkata’s Government College of Art and Crafts and started working at Mandar Studios, India’s first animation company, where he developed drawing skills under Clair Weeks, an animator who had worked at Disney. Pyne started developing his visual language during this period, absorbing ideas from world cinema inspired by movies like La Dolce Vita and The Seventh Seal, where pictures usually said more than words.

His earlier works were more anchored in everyday life and brighter. But as time went on, his work got more introspective, quieter, and more profound. Financial difficulties in the 1960s led him to downscale; he began producing tiny ink drawings rich in emotion and complexity. That time of simplicity eventually led him to tempera, the medium that defined him.

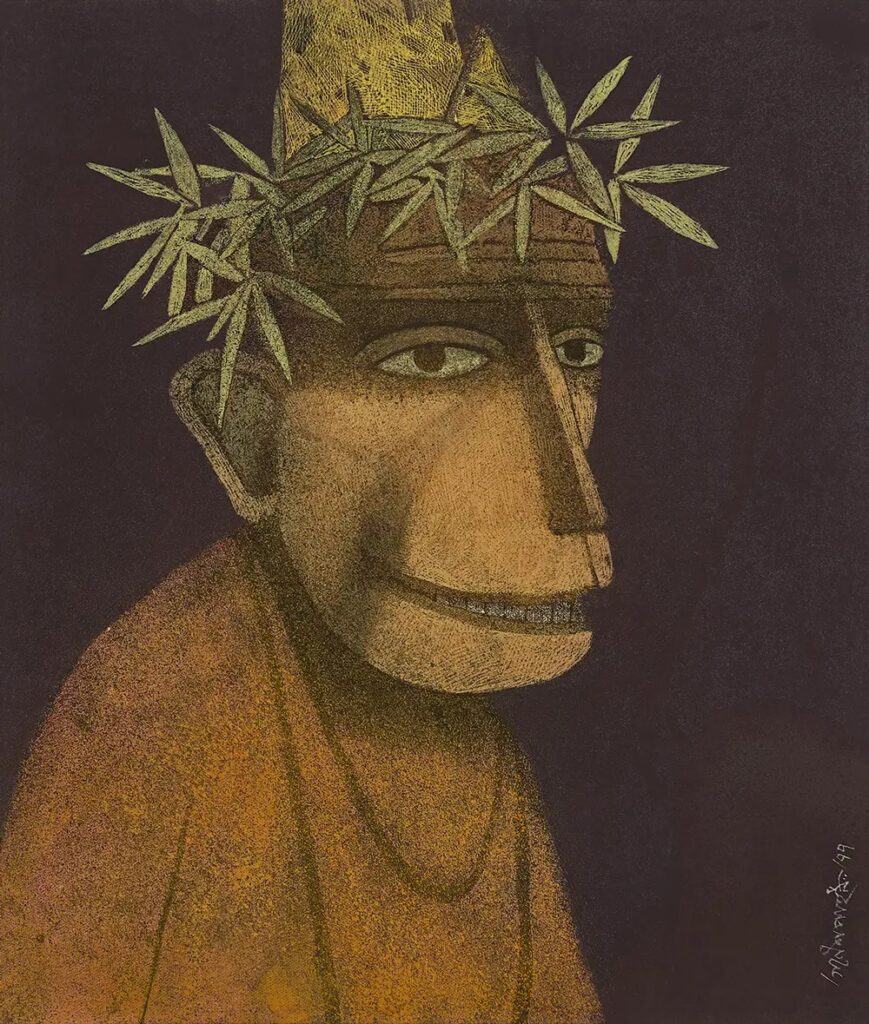

From the mid-1960s, Pyne’s works are filled with odd, symbolic figures—jesters, warriors, ghosts, and creatures seeming half-real, half-imagined. For him, the jester was a mirror of his worries, particularly throughout times of uncertainty, rather than just a figure.

Mother and Child (1961), one of his early creations, reveals another aspect of him. The painting is gentle, mellow, and silent, a seldom-found instant of calm. It reminds us that Pyne’s work was about all the nuances of the human heart, not only about darkness.

He was a quiet man, not one to pursue notoriety or market awareness. He rarely granted interviews and stayed apart from the glare of the art scene. Still, quietly but surely, his impact has lasted. His work was depth-oriented, not about quantity. Every painting communicates slowly, purposely, and with much emotion.

Pyne’s contribution to Indian art

Importantly, Pyne was among the few modern Indian artists whose work merged deeply personal narrative with a visual idiom that was entirely his own. He developed a lexicon of recurring symbols—crowns, skulls, masks, and spectral forms—that became central to the way viewers interpreted themes of fear, transition, and memory in his oeuvre. He was an early member of the Society of Contemporary Artists, where he engaged with fellow modernists while continuing to evolve a deeply individual visual language.

Pyne’s contribution to Indian art lies not only in the visual brilliance of his work but also in how he shaped a distinct modernist language rooted in Bengal’s cultural memory. His paintings often appear as pages from an unwritten story—quiet, surreal, and emotional. In doing so, he brought a form of Bengali Gothic to the national consciousness, one that merged local folklore with psychological depth.

He was not just a chronicler of inner life but also someone who showed that Indian modernism could embrace the intimate and the metaphysical without losing cultural specificity. Unlike some of his contemporaries who leaned toward bold abstraction or overt political messaging, Pyne carved a quiet, reflective space within the larger art narrative. His canvases acted like thresholds—drawing viewers into an emotional landscape steeped in stillness, but rarely silence.

Collectors, curators, and critics today continue to revisit his body of work for its subtle commentary on the fragility of existence and the complexity of inner worlds. His paintings are part of major collections and have consistently resonated in the secondary market, yet they remain emotionally untranslatable in any purely commercial sense—a testament to their enduring mystery.

In many ways, Pyne stands as a bridge between tradition and modernity. His works echo with the rhythm of old Bengali tales, yet their structure and symbolism speak to modern anxieties and metaphysical dilemmas. This duality—of past and present, of seen and sensed—is what ensures that Pyne’s work continues to be studied, exhibited, and quietly revered.