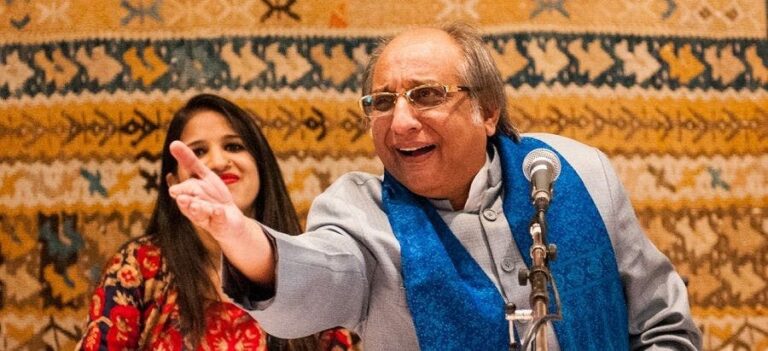

Hindustani musician Iqbal Ahmed Khan gifted Dilli gharana with a new ring of beauty during his six decades of vocals

Iqbal Ahmed Khan sang for a good six decades even as his life came to an abrupt end at the age of 66. The track record shows the classical musician’s prodigious start and a tenacious career that further decorated Dilli gharana as the oldest school of Hindustani khayal. The ustad was saying his prayers in the wintry morning on Thursday when he suddenly collapsed at his home in the Walled City area of Delhi. Doctors at the neighbouring hospital confirmed he suffered a cardiac arrest.

Khan, a pious Muslim, habitually referred to Allah in his conversations — long or short, about the arts or otherwise. A music-soaked family atmosphere was what primarily led his dastangoi-practising daughter Vusat Iqbal Khan and her husband Mohd Imran Khan to support the ustad’s creative ventures. That apart, the patriarch would attribute the household’s cultural pursuits to the magic of the almighty.

The singer possessed a slightly nasal voice with a streak of fizzle that made his music all the more tender. For a gharana that seldom had females in its grand lineage tracing to Sufi poet Amir Khusrau (1253-1325) under the Delhi Sulanate, Khan’s daintiness in rendition always bore the potential to lend his school a novel charm.

Krishna Bisht, 77, who turned out to be the first woman to appear along with the seven-century-old graph of Dilli gharana, highlights Khan’s versatility. “He could sing every genre in the system. And prove his prowess as a composer,” says Bisht, who worked as a music teacher with Delhi University.

Composing eminence

In fact, the ustad lent tunes for television programmes too. That was more so in the 1980s when Doordarshan enjoyed a monopoly as the country’s lone audio-visual broadcaster. These include serials such as Indra Sabha and Police File Se, besides documentaries and telefilms including Yaad-e-Ghalib, along with plays Tamasha or Tamashai and Jahan-e-Khusro among others, points out the Sangeet Natak Akademi, the country’s apex cultural institution under the government.

That slice of contemporariness apart, Khan unmistakably conducted as a quintessential Hindustani musician. Speaking in sentences dense with Urdu words, he spread the charm of an old-world etiquette. The body language carried signs of unintended dramatics, but he was least pretentious when his eyes sometimes welled up at the casual mention of his benefactors. His pride in being a scion of the Dilli Gharana had no bounds.

“For a gharana to solidify, you need to wait for its features percolate down some four generations,” Khan used to opine. “Khayal is about imagination, but it needs some musical consistency to be labelled as a school.”

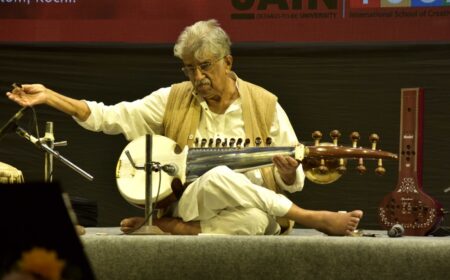

Nonagenarian instrumentalist-scholar Arvind Parikh, who is a staunch believer of gharana music despite large-scale intermingling of schools in the 20th century, notes how tough it was to “catch hold of” a busy Khan. “He will be either engaged with his students, teaching them. Or travelling around and performing,” says Padma Bhushan Parikh, based in Mumbai.

Life and art

The artiste was barely four years old when he began joining his elders on the concert dais. “I was groomed in a household that reverberated with sa-re-ga-ma all the time,” he would recall. “In fact, elders used to sing for me specifically when I was an infant of just three months.”

The illustrious Chand Khan was young Iqbal’s chief guru. That relation lasted till 1980, when the master died at the age of 81. The next year, Ahmed Khan, only 27, was anointed the Dilli gharana’s overarching khalifa. And he served that slot for four decades, winning amid it a string of honours — the top among them Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2014).

Maestros such as Hilal Ahmed Khan and Ustad Naseer Ahmed Khan, too, trained Iqbal in a big way. “My grandparents effectively breathed music into me,” he would reminisce. “As a child, I lay with my Dada on hit cot. That continued to be the habit — till I was 27 years old.”

The formative years being spent with wise men did have a telling effect in the character of Ahmed Khan. As sitar exponent Debu Chaudhuri notes with reference to the ustad, “As a musician, you need to not just become a good artiste. You must also be a noble human being. It’s a great blend.”

Khan, besides being a top-grade artist of Akashvani and Doordarshan, was a regular at several pivotal music festivals. A scholarly approach to the art also fetched him invitations to symposia and workshops on music within the country and in the West as well. Kathak icon Birju Maharaj used to hail the ustad’s capacity to bring out the shades of a raga through apt modulations. “His throat would work the ideal way.”

Ustad Iqbal Ahmed Khan believed that music, like the world, would keep changing and evolving over time. “It’s only positive development. Only, you need to be wise enough to incorporate the good ones into your idiom without disturbing its fundamental aesthetics.”