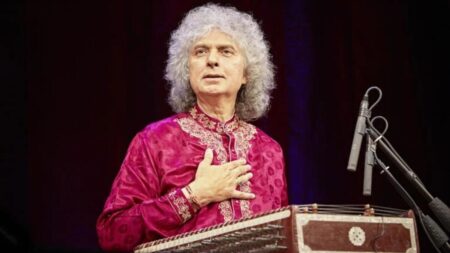

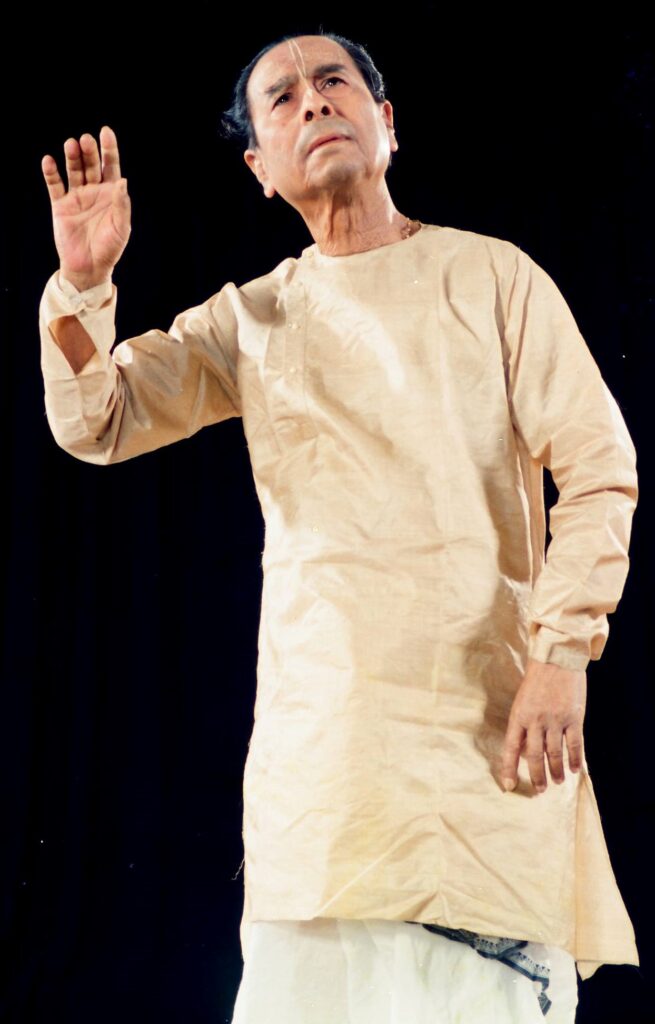

Darshana Jhaveri is a frontline Manipuri dancer, coming from a Gujarati family. She turns 82 today, coinciding with the death anniversary of her teacher Bipin Singh. A look at the two maestros.

On her 60th birthday two decades ago, Darshana Jhaveri lost her pivotal Manipuri dance master. Guru Bipin Singh was 81 when he breathed his last on this date in 2000. The exit left a void in the eastern Indian classical art-form he performed all his life. Today, the disciple turned 82 — amid her efforts to further popularise Manipuri beyond its homestead.

Darshana is part of what used to be a fabulous Gujarati foursome who decorated Manipuri in their heyday. Nayana, Ranjana and Suverna, besides Darshana, gained fame as the Jhaveri sisters, earning a special mention in the 20th-century history of Manipuri. Rajasthan-born Nayana passed away in 1986, aged 59. Ranjana, 87, died in January 2017. Suverna retired from dance in 1987 when she was 52. Darshana lives in Mumbai, where she was raised.

The western metropolis was where Singh began teaching Nayana and Ranjana. The master had reached the big city as a 25-year-old — from Khandala to where he had fled as a late teenager from the remote Singari village in what is now southern Assam. It was in 1945 he started giving classes to the two elder Jhaveri sisters. A couple of years later, Suverna and Darshana too became his disciples.

It all began in the middle of that decade when Singh included Ranjana in a dance-drama titled Jai Somnath. That led to more such productions. “We were very impressed by his compositions, creative genius and scholarly attitude. After knowing him, we decided that Manipuri is the right style to specialise in,” Darshana recalls in a 2008 interview. The sisters were moved by the “lyricism, grace and devotional quality” of Manipuri. “It suited our nature, body and psyche. The guru also noticed that the natural grace required for Manipuri was there in all four of us.”

Advanced lessons from Manipur

Such was the interest of the sisters in the dance that it took the Jhaveris to the art-form’s native land of Manipur. All four left for hilly Imphal, beginning with the two senior sisters in 1949. There, the siblings learned also under gurus Amubi Singh, Amudon Sharma Atomba Singh and Kshetritombi Devi.

They stayed in the cottage next to Guru Amubi in 1956. “The experience of watching ‘Raslila’ and ‘Sankirtana’ changed our lives. We began to visit Manipur and learn different classical forms of the dance,” Darshana notes.

Soon the sisters were initiated to the Vaishnavite texts. It opened to them opportunities to collaborate with the guru and collect as well as record oral traditions from other masters of the region. “They were in old Bengali, Maithili and Brajabuli language,” recalls Darshana. “We had to establish the scientific tenets underlying the oral tradition. Guruji developed each element and re-choreographed it for theatre.”

Darshana highlights Manipuri property of striking a delicate balance between movements of the different parts of the body without emphasis on any one part. “The swaying movements of the neck and torso are inspired from the bamboo trees lilting in the breeze,” she observes. ‘Raslilas’ and ‘Sankirtan’, as highly developed aesthetic forms, reveal the religious feelings of Manipuris. ‘Raslila’s would be overnight affairs in the temple courtyard.

The Jhaveri sisters brought it within the two-hour frame. This, by picking up one element at a time and trying to make it technically rich in movements and rhythm patterns. “We performed solos, duets and group dances. We remained rooted in the tradition of ‘Raslila’ and ‘Sankirtan’.”

Overall, as late critic Sunil Kothari noted, the Jhaveris “are responsible for bringing the temple tradition of Manipuri dance to the cities.”

Praiseworthy efforts

Into the decade after Independence, the sisters began performing together all over the country and even abroad. In 1958, they became the first non-Manipuris to perform at the haloed Shri Govindaji temple inside the royal palace of Imphal. Six years later, the sisters established a Manipuri Nartanalaya with Singh and Kalavati Devi — first in Mumbai, and then at Kolkata and Imphal. Darshana, with her guru’s assistance, went on to publish several books and articles on the dance. She gained reputation as a meticulous teacher and knowledgeable researcher.

As for Singh, he learned under several gurus Manipuri compositions, the mnemonic syllables and on how to play the pung. His outstanding contribution, according to Dr Kothari, is the deep interest and ability to inquire into shastric aspect of Manipuri.

Singh worked to make Manipuri “stage-worthy” for urban audiences. “When I saw Maharasa and other Rasalilas at Imphal, I could see what Guruji was doing in terms of editing,” he adds. “His constant endeavour was to see that Manipuri was not a folk dance form, as it was earlier believed. It had strong shastric base and shared several elements of Natyashastra even in the seating arrangements of the chief person during Maharasa.”

Both Darshana and Singh won the Sangeet Natak Akademi award. The disciple went on to be honoured with the Padma Shri (2002).