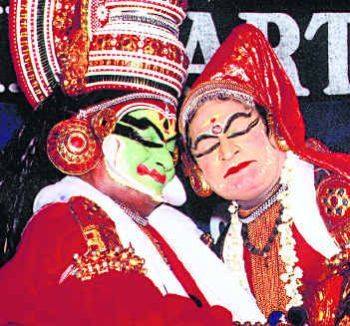

At 84, Kalamandalam Gopi maintains the same lightness and buoyancy in his movements as in his thirties. The grand old guru’s contribution to the art form is unparalleled.

Kalamandalam Gopi turns 84 on May 23. But for the pandemic, one could imagine the zeal with which his aficionados across the country would have organised celebrations, the proportions of which would have been astronomical. More so, since those in connection with his 80th birthday are still fresh in our memory.

According to K Bharatha Iyer, author of the first English book on Kathakali, “A Kathakali artiste at sixty rarely thinks of retiring. He maintains the same lightness in his spring, the same buoyancy in his movements and the same fluidity in his lines as in his thirties”. Going by the track record of Gopi, Iyer’s remarks seem to have been proved prophetic.

Ask him about his artistry and the elegance of the chiseled movements. He would impute them all to the almighty and his gurus. True, his gurus who fashioned him were celebrities known for enforcing the rigorous disciplining of the kalluvazhi chitta that was perfected in Kalamandalam. Difficult task masters that they were, Kalamandalam Ramankutty Nair, Kalamandalam Padmanabhan Nair and Vazhenkata Kunchu Nair shaped the young talent in the mould of this chitta. Fortunately for Gopi, the foundation was earlier laid by another doyen, Thekkinkattil Ravunni Nair. Admittedly, Gopi is the manifestation of this amazing school.

Relentless training

The late Padmanabhan Nair used to recall how intelligent his young sishya was during his student days. Among his contemporaries, he alone attracted minimum punishment, an integral part of Kathakali training. The rigours that lasted for seven long years were beyond description. They remind one of the words of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “It is no small advantage to have a hundred Democlean swords suspended above one’s head; that is how one learns to dance, that is how one attains the freedom of movement”. But it yielded the result – a versatile artiste and an evergreen performer of ‘pacha’ vesham. And perhaps what enables this octogenarian to execute jaw-dropping sequences of pure nritta during the kalasams with the same suppleness of his younger days was this strict formatting he underwent during those formative days.

Pacha is the hallmark of pious characters and is the most glorious one. The vesham assumes an ethereal beauty when Gopi adorns it. Interestingly, Gopi’s pacha vesham has come under the scanner of many painters and sculptures. All of them have vouched for its archaic finesse, both technical and aesthetic. Even when Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair was ruling supreme, Gopi had completed the ‘thiranokku’ (curtain-look) of his pacha vesham. In this connection one recalls the comments of the percussion wizard of yesteryears, Kalamandalam Krishnankutty Poduval, on the death of Kalamandalam Krishnan Nair, “After Krishnan Nair, pacha is gopi”. The pun in ‘gopi’ was quite intelligently used by Poduval.

Epitome of aesthetic beauty

But his propensity for creativity is equally discernible when he enacts kathi veshams like Keechaka or Ravana. Arjuna in Santhanagopalam, Bhima in Kalyanasougandhikam, Roudra Bhima in Duryodhana Vadham – all receive a touch of distinctiveness when Gopi portrays them. Of course, sringara scales to dizzy heights when ‘the couple on the kathakali stage’ Gopi and Kottakkal Sivaraman assumes varied roles especially Nala and Damayanthi. The wavelength-match between the two is still an ardent topic for discussion in the kathakali circles.

Myriad are the choreographers from the West who have explored his inimitable artistry. The Canadian choreographer Richard Tremblay’s Iliad in Kathakali would have been impossible but for Gopi’s involvement.

A performer with a humane outlook and awesome camaraderie, Gopi’s buffs are a legion spread over the entire globe. And they are his weakness too. Their concern for him was evident a few years ago when Gopi faced serious health problems. His ability to inculcate a sense of pride into his fraternity, especially during his stint as the principal of Kalamandalam, has been praiseworthy.

And what he has to say as he looks back: “Really a sense of satisfaction that I could rise to this level through the art of my choice and not in any other capacity. But also a sense of disenchantment: accolades to Malayalee artistes from Delhi are very few and far between”.