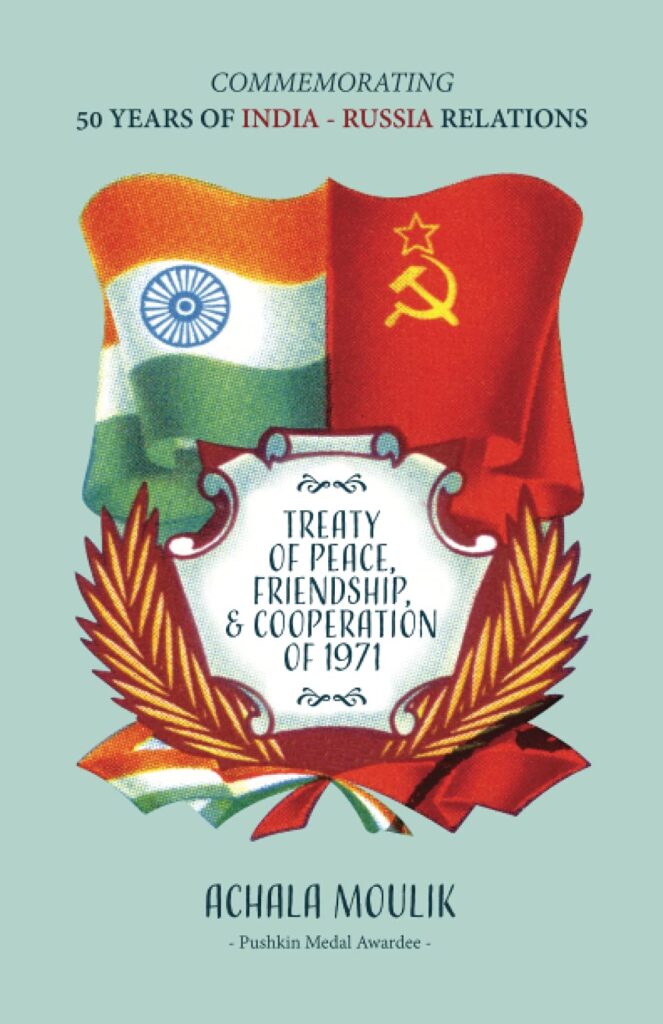

Achala Moulik’s book argues India’s relationship with Russia is no less important today than it was in the past

Achala Moulik is a former senior member of the Indian Administrative Service and the author of several historical and literary works. Her play, Pushkin’s Last Poem, was staged to much public acclaim in Delhi (2007), St. Petersburg and Moscow (2009). She was awarded the Pushkin Medal for the promotion of Russian literature. It was presented to her by the Russian President in Moscow in 2011.

A keen student of European history, Moulik developed a deep appreciation for and understanding of Russia while a student pursuing economics and economic history at the University College, London. Her deep understanding of Russia comes through in her well-received 2017 book, The Russian Revolution and Storms Across a Century.

Her latest book, Treaty of Peace Friendship and Cooperation of 1971, Commemorating India-Russia Friendship, offers a historical background to the most consequential treaty India has ever signed — the 1971 Indo–Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation.

The treaty was not an opportunistic one but a logical ‘next step’ in a relationship between India and Russia that had been warming for a long time. As Moulik explains, “In a wider perspective the achievement of the Peace Friendship and Cooperation Treaty should be viewed as a result of long-standing friendship and trust between both the nations.”

Author: Achala Moulik

Publisher: Authors Upfront

Price: Rs 495

Old ties

Moulik teases out the historical and cultural links between the two countries as well as Russia’s interest in India. It will come as a surprise to many to know that Russian interest in India is over two centuries old. The Institute of Oriental Study, which has an India focus, was established in Moscow as far back as 1818. A similar one, the Institute of Oriental studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Saint Petersburg, was set up in 1823.

Few Indians are aware that Russia was the only country to support the Indian revolt of 1857. Later in 1908, the Russian Consul in Bombay openly expressed his support for Indian revolutionaries, particularly Bal Gangadhar Tilak.” Both these find mention in Moulik’s book.

Indians too have had a high regard and love for Russia. This best comes through in Tagore’s celebrated Letters from Russia. Moulik covers it in her book along with accounts of other enriching cultural exchanges between the two countries all through the Soviet era. Nehru, much taken in by the planned Soviet economy, adapted it for India’s more open democratic environment.

Russia’s significant contributions to India’s development — now largely forgotten — are well highlighted by Moulik. “During India’s second five year plan (1956-1961)”, she tells us, “eight heavy industrial projects were built with Soviet assistance… Between the late- and mid- 1950s, the Soviet Union gave India economic aid of $681 million which was one-third of what the Soviet Union offered as aid to other Asian countries.” We also know from her that the Bhilai Steel Plant as well as IIT-Bombay came up with Russian assistance.

A friend in need

The immense value of Russian economic and military assistance was even acknowledged by Chester Bowles, a former US ambassador to India, in a 1971 article in Foreign Affairs stating that “The U.S.S.R. has helped expand the production of steel and heavy electrical equipment and has provided close to one billion dollars to modernize India’s army, navy and air force.”

The Indo-Soviet Treaty of 1971, Moulik states, marked a “turning point in India’s traditional non-aligned policy so vigorously enunciated at Bandung in 1955.” Even following the India-China war of 1962, when the temptation to join an American alliance was at its greatest, India under Jawaharlal Nehru continued to remain non-aligned.

However, circumstances in 1971 were very different from those of 1962, justifying an alliance with the former Soviet Union. It was a time of grave danger for India from America. The latter was ready to punish it for having intervened in East Pakistan to end an on-going genocide of its people by the then Pakistani government, going so far as to encourage China to attack India.

Moulik is clear that India’s victory over Pakistan in 1971 would not have come about without the Indo-Soviet Treaty “signed on 9 August 1971 by the foreign ministers of the two countries, Article IX of which required the two countries, when threatened, to enter into “mutual consultations in order to remove such threat and to take appropriate effective measures to ensure peace and the security of their countries”.

Given the geopolitical situation in the subcontinent, Pakistan was seen as an indispensable ally by America. It had facilitated Kissinger’s epoch-making secret visit to China in 1971 and significantly aided the emergence of a seemingly improbable Sino-American front against the Soviet Union. That in turn contributed to the coming together of the Soviet Union and India. The Indo- Soviet Treaty of 1971, Moulik asserts, “became a robust counterweight to the menacing Washington-Beijing-Islamabad axis.”

Unknown aspects

Moulik’s book brings out how a mutual unstated wariness of China bound India and Russia together. As Moulik observes, “The Soviet leaders believed that a strong neutral India would counter Chinese expansionism as well as Western influence on the subcontinent.” We need to recall that Russia had its own border issues with China. The two countries had fought a brief bitter war in 1969.

Moulik’s book restores to our collective memory the key role Indira Gandhi played in India’s victory in the 1971 war — a fact that is now being vigorously downplayed. As she states, when matters came to a head, it was Indira Gandhi who “shed the policy of non-alignment and accepted Soviet support for the forthcoming conflict.”

Moulik highlights the contributions of India-loving Russian diplomats in strengthening Indo Russian friendship even after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. She knew several of them personally and she was a very good friend of Alexander Kadakin, a much-loved former Russian ambassador to India and an Indophile. Moulik’s mentions how deeply saddened she was by Kadakin’s sudden demise in January 2017 and she dedicated her book, The Russian Revolution- Storms Across a Century, to him.

A remarkable relationship

Moulik’s book doubles up as an illuminating account of post-World War II conflicts and international developments leading up to and following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It succinctly covers all the principal events that have had a bearing on post-Soviet Indo-Russian relations e.g., American interventions in West Asia and Afghanistan, the challenges arising out of the rise of China, the emergence of the Indo-Pacific theater as an area of potential conflicts as well as the more recent formation of the QUAD.

The durability of Indo Russian relations is well known by many in the West. As one of them, Emily Tamkin, the US editor of the New Statesman, writing in Foreign Policy observed, “There was also the reality that India mattered quite a lot to the Soviet Union, which considered it more consistently than the United States did.”

Not many today realize that for India caught in a fraught security environment, its relationship with Russia is no less important today than it was in the past. India understands this very well as can be seen from its refusal to condemn Russia for its intervention in Ukraine and the conflict that is raging there.

Moulik’s book, published on the 50th anniversary of the Indo–Soviet Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Cooperation, is a timely reminder of an extraordinarily warm and trusting relationship India enjoys with Russia. This has endured despite the latter’s growing friendship with China and India’s own deepening engagement with the West.

This remarkable relationship deserves to be nurtured with great sensitivity by India, especially now, when Russia is no longer the formidable superpower it once was and is acutely sensitive about that, even more so now when, following its intervention in Ukraine, stands isolated from the rest of the world.