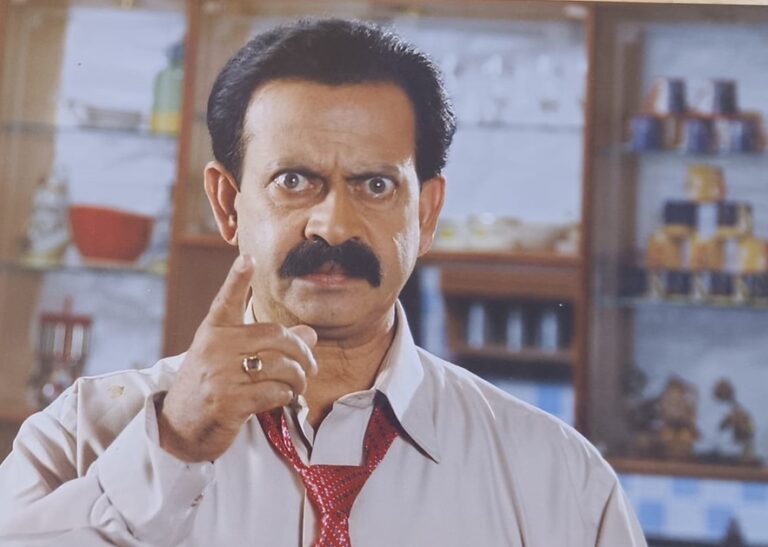

Renowned Kannada artist Srinivasa Prabhu, celebrated for his multifaceted talents in acting, directing, and voice-over, emerges as a stalwart promoter of Indian culture globally. With a postgraduate degree in Kannada Literature and training from the National School of Drama, his journey spans over three decades, marked by notable contributions to Kannada cinema and television. His monodrama ‘Bimba’ garners acclaim, bridging cultural gaps in London. In an exclusive interview with India Art Review, Prabhu reflects on his artistic odyssey, discussing the genesis of ‘Bimba’ and his vision for Indian theatre abroad, alongside his collaborative efforts with daughter Anvi to infuse contemporary flair into traditional narratives on UK stages.

How did the concept of ‘Bimba’- monodrama originate?

The play is based on the life and works of the well-known dramatist Swami Venkadari Iyyer, known by his pen name- Samsa. He battled with a persecution complex and tragically committed suicide at the young age of 40 in the year 1939. Despite being innocent of any crime or involvement in riots, he had an irrational fear of being pursued by the police, ultimately leading to his untimely death. He was a representative of the Indian youth of that period, who were experiencing various anxieties and societal pressures.

He authored many plays within his short lifespan, approximately 26 of which remain, as he destroyed several of his works. During my MA, one of his plays was our textbook. I was truly drawn to his works, and he began to haunt my thoughts. The character, the mental state he had gone through, his thoughts, psychological states, etc., sparked a desire in me to bring his character to life in ‘Bimba’ out of admiration for his works and a fascination with the human psyche.

Why did you choose to present ‘Samsa’ as a monodrama, and how did you structure the plot?

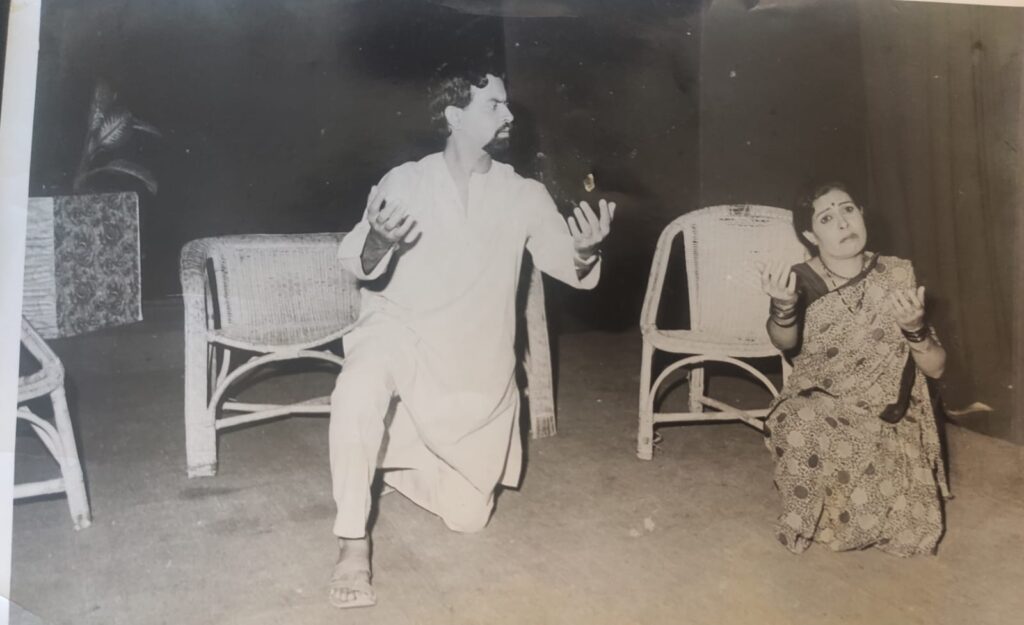

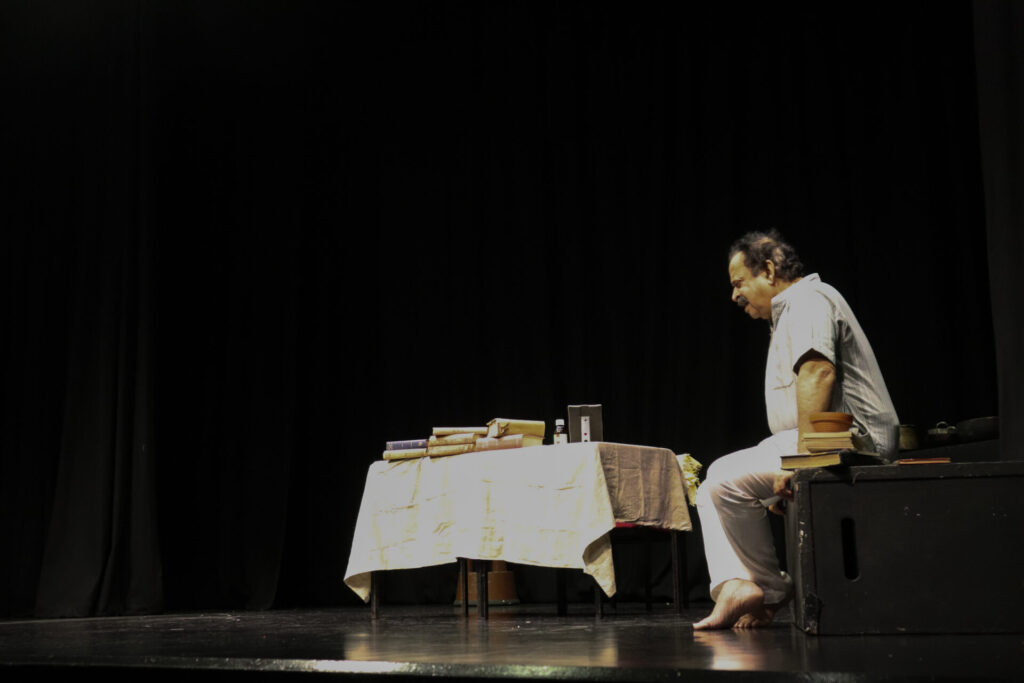

When I got the opportunity for a monoplay, ‘Samsa’ was the character that came to mind. I found immense scope in presenting Samsa as a monodrama. The play was developed in such a way that Samsa was talking to himself, in a monologue type. He stayed alone in a room, almost always closed off, hardly speaking to anybody. Many of his contemporaries tried to convince him to understand the reality, that “You are not a criminal, nobody is following you,” but he was not ready to accept any support from anybody. I tried to bring all these elements into the play as his introspections. The play is structured as Samsa talking to the mirror—that’s why the name ‘Bimba’—the Reflection. In this way, the character speaks to his image—the Bimba—expressing his introspections through his dialogues.

Bimba was made into a film as well? Then why return to drama?

Yes, one of my friends approached me to adapt it into a film. The subject matter was unconventional, a period piece, and we were doubtful if any producers would be willing to take it on. So, we decided to film the play itself. The film titled ‘Bimba- Aa Thombatthu Nimishagalu’ portrayed the last 90 minutes of Samsa’s life. He stands with the poison bottle, waiting for the ‘Muhurtha’ to drink it. During this time, he reflects on his life within those 90 minutes. Props like a beedi bundle, a clock, a mirror, and some scripts each unfolded different stories of his life. The film was a single-shot one, with me as the solo actor. We received a national record for this approach. It was screened at various prestigious festivals. At the Rajasthan Film Festival, we won the Best Regional Film award.

However, it was not artistically fulfilling for me. In theatre, the performer enjoys freedom; we create our own space. In the film, the technique is different. Theatre is an actor’s medium, while cinema is the director’s medium. After the film, whenever I was asked to restage the play, I was thinking, why should I? After all, the film is accessible to anyone at any time to watch. But it was my daughter, Anvi, who insisted and motivated me to revive the play and restage it in London. Thus ‘Bimba’ came on stage, six years after the film adaptation.

Now, how do you feel after bringing it back to the stage?

This time it was a culmination of elements from both the original play and the film adaptation. I reframed it. Now, I feel a strong desire to be on stage. Theatre brings me immense pleasure. For an actor, theatre is prime. It’s a medium with a lot of challenges. There’s no option for retakes, as in films. This brings me immense pleasure and fulfillment.

Monodrama is a unique concept in theatre. How do you perceive the possibilities and challenges of monodrama?

Monodrama stands apart from casual monoacting, which is a common sight on school and college stages. This genre involves the exploration of characters, situations, emotions, and introspections. It is entirely philosophical, involving analysis and interpretation—all conveyed through soliloquy. Effective structuring is crucial, or else it might slip into mere mono-acting.

Maintaining the audience’s attention throughout is another significant challenge, as there are no other performers or any big, colorful attributes. The voice typically plays a significant role in theatre, even more so in monodrama. Through vocal modulation, we have to bring in smooth transitions. All these are challenging but interesting aspects of this type of performance.

Another great aspect is that the performer enjoys complete freedom in their presentation style. They are not dependent on others or their convenience, and there’s no need for carrying big props or sets to be prepared beforehand. Nowadays, this style receives widespread acceptance, with a significant number of female performers also excelling in it.

You’ve worked in television, cinema, and theatre. How do you differentiate these forms as a performer?

My guru, Karant, often says that in film, you’re about enlargement; in TV, you’re minimized, and in theatre, you appear as complete and real, with the character residing within your body. I have experienced these differences. Cinema and TV are more commercially driven and massive industries. You will receive popularity and money, but as an artist, I find Theatre as my ultimate medium. I worked for TV and Film as part of my career, but if I stand for myself, my own pleasure, and development, I choose only theatre.

How do you see the younger generation’s entry into theatre?

There are many talents, but one cannot survive solely on this, especially in amateur theatre. Beyond commercial and amateur, there is a trend toward commercial plays these days. They mainly focus on gimmicks, and unnecessary additions of dance—just to add ‘colors’. For professional theatre, certain venues and groups of audiences watch it as an art.

In amateur theatre, the focus is more on social dramas—stories that tackle socially relevant or realistic themes that anybody can connect with. Many artists have chosen this as their full-time profession. While there is an audience, it often falls short in terms of numbers. In recent years, very few plays have managed to cross 500 performances. One exception in my experience is our play “Mukhyamanthri,” which crossed the 1000-performance mark, though not within a year or two, but over 20 years.

Theatre culture varies across different states and cities. In Maharashtra, it’s particularly prominent. In Karnataka, while it’s strong, the frequency of performances and repeat shows is comparatively lower. Naturally, theatre artists who have to find their livelihood only from acting would themselves turn to television or film. But I am happy that many talented young people continue to enter the theatre scene out of passion. There are reputable institutes that offer professional training as well, but opportunities in the field are still to be explored.

When you perform overseas, you represent a regional narrative, a language, or a piece from your culture. How do you view the market for this abroad today?

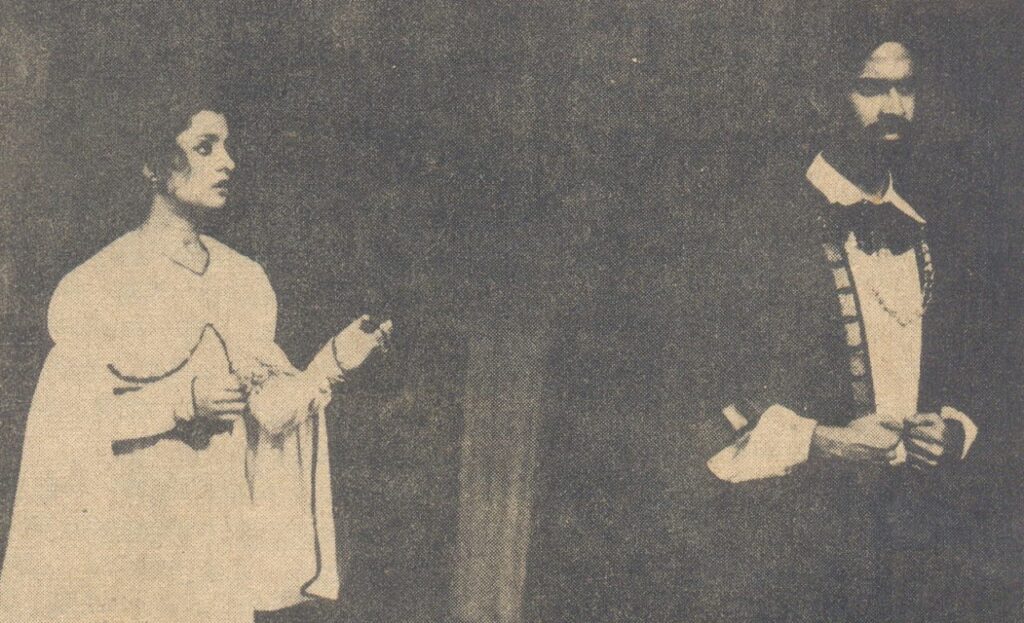

It’s indeed quite challenging. Creating awareness about the art form is a difficult task, but that’s what we focus on first. Spectators must familiarize themselves with the performative techniques and language. So when I reached London, Anvi and I started trying out plans for some experimental works—a fusion of two cultures or so. For example, presenting a Shakespearean drama in the style of Indian traditional performances, either as Yakshagana or any other regional Indian style. The format belongs to them, while the subject belongs to us, or vice versa—such as “Shakuntalam” in English, etc.

Have these areas been experimented with or studied already?

Yes, there are numerous ongoing researches and experimentations in this field. We are actively engaged in exploring these directions.

Getting publicity may not be a big challenge these days, but what other attributes are you focusing on? Are there any plans to integrate new technologies or special measures to disseminate Indian theatre in the diaspora?

Anvi answers: As I understand, the market varies from place to place. London, being a multicultural city, already has a diverse audience. So finding a target audience is relatively easier, especially for English plays.

The big challenge lies in taking our art to a multicultural audience and ensuring that everyone can enjoy it. In smaller cities, we must be mindful when we use regional contexts. Understanding the “what,” “where,” and “who” of our target audience is crucial, and this varies depending on the purpose of the production as well, whether it is for entertainment or addressing socially relevant issues. These are questions we must address right from the outset of production. So new measures will be used as trials and errors might happen, but we learn from them.

You’re passing on your lineage to your daughter. Are you also involved in cultivating a new generation of theatre artists, especially in the diaspora? Are there any efforts in that direction?

Yes, of course. We’re planning workshops for young artists and aspirants. As Indian artists, we are fortunate to inherit a rich cultural heritage. With this in mind, we’re developing a special pedagogy for acting students, incorporating concepts from Indian dramaturgy—Natyasastra. This is a major project for us, focusing on raising awareness about how Indian concepts are influenced by Western thinkers.

I am also keen on reviving Indian classical plays with minimal expenditure. I’m not towards big-budget productions; instead, I always stand for ‘poor theatre.’ This approach focuses on the quality of acting and scripting over highly expensive production elements. Our body is our instrument; an actor should bring out the full potential of our capabilities. Together, we have started this new journey in that direction. Let’s see how it flourishes in the diaspora.