India’s first theatre-for-the-internet conjures up a disturbing virtual world where hope, loss and power engage in a riotous conversation.

I ‘experienced’ Amitesh Grover’s The Last Poet in December 2020. The second wave of Covid-19 was yet to come and the world was opening up a little. There was hope in the air. I was recovering from chest congestion that pinned me down to the bed for weeks. So, I watched Grover’s digital, interactive performance propped up on a high stack of pillows, which itself was a weird experience.

In a normal world, you won’t be watching a theatre performance if you are unwell and can’t travel. But these are different times and a different world. Boundaries between the real and the virtual are liquefying. It hardly matters if you are going out or not. You are spending more than a half of your waking hours in this virtual world, attending meetings, teaching, learning, chatting… so much so that at times you confuse the real with the virtual, and vice versa.

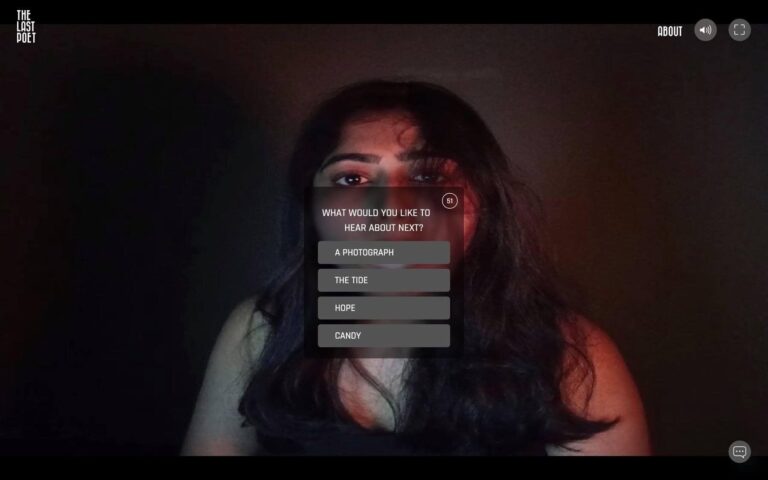

It is this ambivalence that powers The Last Poet. What, or who, exactly is The Last Poet? One could say that it is a ‘cyber theatre’, or a multilayered art form with theatre, sound art, creative coding, digital scenography and live performance, or online interactive performance. Grover, a Delhi-based interdisciplinary artist, calls it ‘a gender-bending broadcast of theatre, India’s first theatre-for-the-Internet’.

That said, The Last Poet is not your run-of-the-mill online performance. It was produced during the lockdown when several theatre practitioners, locked in their homes, used the cell phone camera to communicate with the world outside. Most of these performances were either solo acts or performed by a closed group (family or friends), and broadcast through social media.

But not The Last Poet. It unravelled a new world before those who logged in to watch the show. The audience entered a cyber space of floating forms, loosely emulating a ‘floating city.’ You could linger around, listen to the eerie soundtrack, move your cursor over the floating bodies and if one of the highlights, you could click it and enter that ‘Room.’ It was your choice. Once you enter the room, you are confronted by the Actor. The actors would start talking to you about a poet who has disappeared. You could continue to listen. Or you could leave that Room. And enter another one as you wish.

Politics of the Web

You meet five actors here – Atul Kumar, Aswath Bhatt, Bhagyashree Tarke, Pallav Singh and Dipti Mahadev. Together, they present 25 characters who tell us about the missing poet. “I was trying to deal with the sense of dystopia when the outside world had completely collapsed,” says Grover. “I was trying to respond to what was happening to our world. The performance spaces were shut down and I turned instinctively to the Internet”. Grover was studying the Web as a part of his work and he was deeply interested in the politics of the Internet, its challenges as a medium, how social media platforms alter human behaviour and the perils of data mining in the age of surveillance capitalism.

“When the lockdown happened, I was looking for a space, a way to keep creating,” says Grover. “The idea of dystopia kept coming back to me. It was also about the collapse of truth itself. Then I started to imagine a world where a poet had gone missing. It was already happening in the outside world.” During the lockdown, intellectuals, academics and writers were being arrested for myriad reasons. “So, the figure of the poet became for me a way to think of the power of the world, of the State.”

Grover went about creating this 3D world, working with a dramaturg, Sarah Mariam, and a team of coders. “We developed this 3D world from scratch, with sketches, drawings, colour palettes.” The work took 5-6 months. The actors were the last to enter the production. It goes without saying that the whole work was created via the Internet. “As a team, we haven’t met offline!” says Grover. All of them were working from different cities. When the actors came in, Grover had to introduce ways of performing for the camera, which was neither borrowed from cinema or theatre. “We had to find a third language, which could be the new language of the media”.

Grover also had to understand and intervene in the politics of the code. “We worked with two principles – the first one monitored the audience movement. If a member is moving very fast, they would automatically try to slow them down. If the algorithm notices you are not moving at all, you are not leaving the room, then the algorithm would start tempting you to leave and move. The second principle was to always distribute the audience across five rooms. There was always an equal number of people in each room.”

The creative tech team of The Last Poet include Praveen Sinha and Gagandeep Singh while Suvani Suri and Abhishek Mathur handled sound, with films by Annette Jacob. Scenography and tech design are by Ajaibghar, a group working on product management and strategic solutions in arts and culture.

For Grover, creative exploration and expression are never confined to any single genre or material or subject or even one single world. The Last Poet is just another foray into that manufactured world of cyber reality, learning and exploring its politics and its semantics. And the exploration goes on.