Panthattam in Mohiniyattam

There are distinct similarities between the lasya movements and the juggling techniques with a ball, described in the dance performances in the seventh century work Daśhakumāracharitaṁ, and Kerala dance forms like Mohiniyattam and Thiruvathirakkali.

After Silapathikāraṁ and Maṇimēkhalai, references to Kerala performing arts, especially those which have resemblances to Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ, have been found two centuries later in certain literary works of the seventh century AD. Daśhakumāracharitaṁ is an important work from this period that reflects the cultural traditions of medieval India. As the title implies, the work depicts a tale of ten princes and is written in prose, in Sanskrit, and is centred around the theme of romance. Experts are of the opinion that Dandin, the author of the work, lived in South India in the seventh century AD, since he had written about Mathrudattan and Bhavarathan, linking them with the Vēdic culture in his work. While Dandin probably hailed from Kanchi, the present-day Tamil Nadu, the stories are set across India, from Punjab to Odissa and from Uttar Pradesh to Kerala. Thus, one can infer that the author was familiar with the culture and traditions of different parts of India which he chose to base the stories of the princess. Experts feel that he might have also had a direct or indirect understanding of the cultural traditions of the regions that are part of the present-day Kerala state. We interpret several of the dance and cultural traditions described in the Daśhakumāracharitaṁ text to investigate the possibility of a resemblance and a direct or indirect relation to contemporary dance forms of South India and Kerala.

Where dancers worship the Bhagavati and juggle balls

Kandukavati enters the stage, which is erected in the centre of a garden. The dancer pays adulation to Durga Dēvi or rather starts with a prayer dance to the goddess. Kandukavaṭi looks captivatingly beautiful, like the goddess herself. (In Kerala, the Bhagavati is goddess Durga) The dancer lifts a red ball deftly with her nimble fingers and drops it lightly as if it slipped down her fingers. She picks it up, bounces it with the back of her hand, and sends it high into the sky. Thus she dances with the ball, throwing it up and down, and the movements gradually turning vigorous. The movements of the limbs are very supple and charming. At times she assumes beautiful positions, such as that of a moving bird. (The balls used by the Ammānāṭṭakkār, artists who juggle while dancing, were red in colour. Interestingly, a few such balls we found during our research were also red)

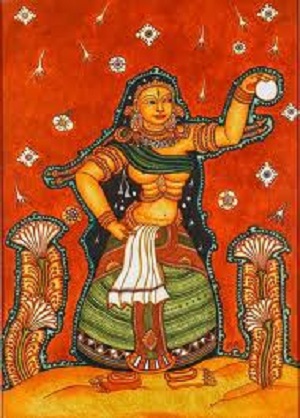

Even while dancing with deft footwork, the dancer keeps up the lāsya movements. It is a well-known fact that Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ is a dance style that gives great importance to lāsya nṛtta. Moreover, assuming different stances, beautiful poses and assuming the movements of a bird in flight are also characteristic to Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ. The dancer strikes the ball with the left and the right hands alternately. Sometimes she lifts it high, sings and dances at the same time as the ball comes down slowly. She whirls and swings. She whirls so fast that one gets an illusion of a static dancer inside a red cage. While dancing she holds the loose end of her dress with one hand. It is remarkable that this pose of striking the ball is depicted in Mōhini statues and mural paintings in temples today. The long disheveled hair, the beautiful sāri that rests luxuriously on the hands, and the unique dance poses; are all depicted in a similar way. From all these descriptions, we can presume that Dandi was familiar with the dance forms which were prevalent in Kerala at the time. It may not be altogether wrong to conclude that in the seventh century itself there existed in Kerala or in the Chēra Kingdom a lāsya dance style which combined the gestures of Pantāṭṭaṁ, Ūññālāṭṭaṁ, and Ammānāṭṭaṁ, along with the Satvika Abhinaya that was performed in praise of the Mother Goddess.

Thiruvathirakkali and Kandukavati’s dance

Parallels can also be drawn between Kandukavati’s dance in Daśhakumāracharitaṁ and a Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ recital of the 20th century. Kandukavati’s dance was actually an offering to the presiding deity of the temple to win a good husband. The Bhāgavataṁ mentions that maidens used to worship Goddess Kārttyāyani with rituals, song and dance, to be blessed with a fine husband. The princess described in Daśhakumāracharitaṁ also dances in worship of goddess Durga – simultaneously juggling. Thiruvathirakkali of Kerala has the same myth underlying it. Every year women dance, sing and practise many rituals during the time of Thiruvāthira. While performing Thiruvathirakkali too, this technique of juggling was frequent and was called Ammānāṭṭaṁ. Even today, while the ritual of pātira pūcūṭal (wearing the midnight flower) is observed, dancers who bring the flowers are welcomed with Ammānāṭṭaṁ.

Pantattam: the common factor

We should keep all these facts in mind while we observe the dance of the princess in Daśhakumāracharitaṁ. Just as Kandukavati commences her dance recital with an invocation to the Bhagavati (Goddess Durga), a Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ recital begins with Vandana dance, also an invocation to the Bhagavati. Similarly, the way the ball is also elaborated on in Daśhakumāracharitaṁ. Parallels can be drawn between the movements in both art forms. At the time of the revival of Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ in the 20th century, Pantāṭṭaṁ, playing with the ball and dancing, was given much importance. The act of playing with the ball is also common for the female characters in Kathakali. Even today the gestures of Pantāṭṭaṁ are very liberally used in Mohiniyattam. In some villages in Kerala, Pantāṭṭaṁ and Ammānāṭṭaṁ are still practised as a part of Thiruvathirakkali, though these customs are gradually becoming extinct. In the olden days, puppets and balls had a prominent role in entertaining women. The tradition of Pantāṭṭaṁ is common to several performing arts in Kerala including Kathakaḷi, Nangiārkūttụ, Kriṣṇanāṭṭaṁ, Kūṭiyāṭṭaṁ and Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ while illustrating the games (dalliances) played by women.

A woman playing with a ball appears frequently in the mural paintings of Kerala as well, and she is supposedly goddess Parvathi. The entire experience of the world is philosophically considered as a playful act by Mayadevi – the philosophical incarnation of goddess Parvathi.

Read Part 6

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardanan)