Carnatic music will become popular only if its advocates reach out to laymen, and address people from different cultural and age backgrounds

Listening to French radio one night in 1977, I noticed a recording by Ramnad Krishnan being discussed at great length. This happened to follow a daily poetry session I loved listening to, so Carnatic music was not what I had tuned in for. Yet, to me, being a student of western music, keen on learning more about all kinds of music, this music was a revelation. To my ears, this music was more than just one among others, each worth appreciating in its own right.

I realised that this experience answered some questions I had long been pondering about. Could there be any music that is, at the same time, ‘ancient’ and ‘flourishing’ in the sense of unbroken continuity with scope for self-expression?

And if such music could be found, would it make someone like me feel welcome? Without having grown up in its cultural context? Little did I know that the second question had long been answered in the US where Carnatic music was in the process of becoming one of the best-studied music traditions ever, thanks to Wesleyan University’s ‘visiting artists’ program that had invited Ramnad Krishnan to the US.

As for the first question, it took me several years of study at Kalakshetra, at the invitation of its founder Rukmini Devi-Arundale, to realise that the history of Carnatic music (including its name and variants like “Karnataka Sangitam”) is a highly contested one. Studying such music was therefore bound to be a lifelong pursuit.

Learning Carnatic

Blissfully unaware of any possible pitfalls that would delay my grasp of Carnatic music, I became a student of flute vidwan Ramachandra Shastry. Learned musicians and scholars guided me on various aspects; most generously Vidya Shankar, S. Rajam and T.R. Sundaresan noted for their ability to brighten the lives of music lovers in often unexpected ways.

As it turned out, Carnatic music is many things to many people, a fact rarely reflected in scholarly works, yet evident wherever musicians, listeners, and learners congregate. Their shared pursuit is all about a joy that transcends – and often contradicts – ‘common sense. This is an attitude valued and clearly expressed in Carnatic lyrics, particularly those of Saint Tyagaraja for whom music was a source of unmitigated bliss and fulfilment, even conducive to liberating oneself from trivial pursuits. Could this be akin to modern concepts like ‘total immersion’ and ‘mindfulness’? For instance in song lyrics like Intakanaanandam, Manasu svadinamaina, Aparamabhaki, Nidhitsaala Sukamaa wherein Tyagaraja also invokes legendary role models in accordance with older conventions.

In other words, does this not sound like a message or ‘remedy’ for some of the ‘ills’ of our times? Like the many distractions imposed by modern lifestyles, our inability to focus on the task at hand, hence putting our most important relationships in jeopardy. The difference being that Carnatic music at its very best relies on a heightened involvement in several realms at once. For this reason, most of South India’s music is hardly suited to be used as a sonic background merely to create a pleasant ambience. This may even stand in the way of ever getting ‘popular among the masses (though some have claimed success in such an endeavour).

From class to mass

This brings me back to what greatly matters to me as regards all Indian music and stated succinctly by Yehudi Menuhin, the violin virtuoso to whom Hindustani and Carnatic music were of equal interest, though mainly remembered in India for collaborating with Pandit Ravi Shankar: ‘An oral tradition is a wonderful thing, keeping meaning and purpose alive and accessible. As soon as an idea is confined to the printed page, an interpreter is required to unlock it.’

Little remains to add to this insight by a globally acclaimed musician, other than asking ourselves. Should we allow our favourite music to be limited by convention or reduced to a ‘definite’ performance, fixed forever on any medium like paper, CD or other digital media?

I doubt this makes sense from any point of view, be it artistic, social, pedagogic or historic. After all, today’s performances hardly look or sound like anything past composers could have anticipated as regards their creations such as padams, kirtanas or kritis. Regardless of a given sampradaya (lineage of gurus and followers), this may have made little difference. Nor have their interpreters objected to the introduction of new, formerly ‘alien’ instruments (tambura, violin, saxophone and electric mandolin); or to the adoption of instruments from dance and folk ensembles (flute, ghatam, kanjira and morsing) – on the contrary, all of these instruments have long since been played by men and women from different social backgrounds, often to international acclaim.

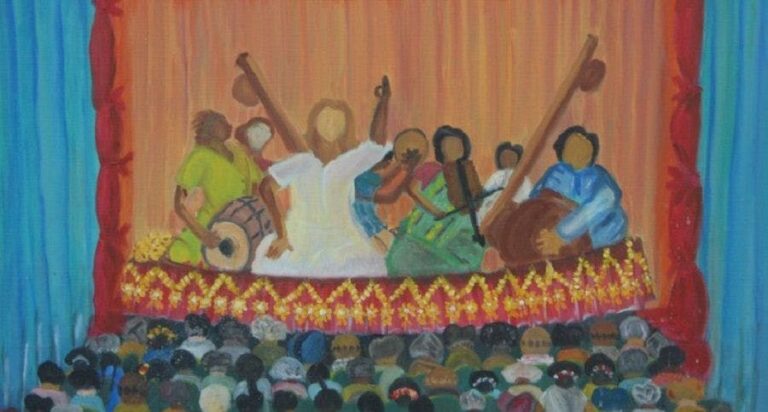

However, the ‘message of revered poet-composers still finds its most congenial expression in community programs rather than in sleek stage and studio performances, going by ‘their key motives in cultural creativity which include, psychological satisfaction and bliss’.

In other words, popularising Carnatic music may well succeed once more if its exponents dare reach out to laypersons instead of reducing them to passivity, treating them as participants again, which they had indeed been not so long ago. This calls not only for patience and creativity but greater sensitivity to the special needs of participants from different cultural backgrounds and age groups.

Republished with author’s permission.