Farah Siddiqui has been in the art world for over two decades. Her journey has been fixed in providing a platform to young emerging artists. An art enthusiast and visionary, she talks to India Art Review about her experience with how the art world has evolved, and what the future beings in a world driven by AI.

Can you tell us about your venture and the initiatives you’ve led in the art space?

I have been professionally involved in the art world since 2004, though my journey began much earlier. Growing up in Delhi, my mother, a journalist, deeply connected to the artistic scene, introduced me to exhibitions, the Festival of India, Russian ballet, and many other rich cultural experiences from a young age.

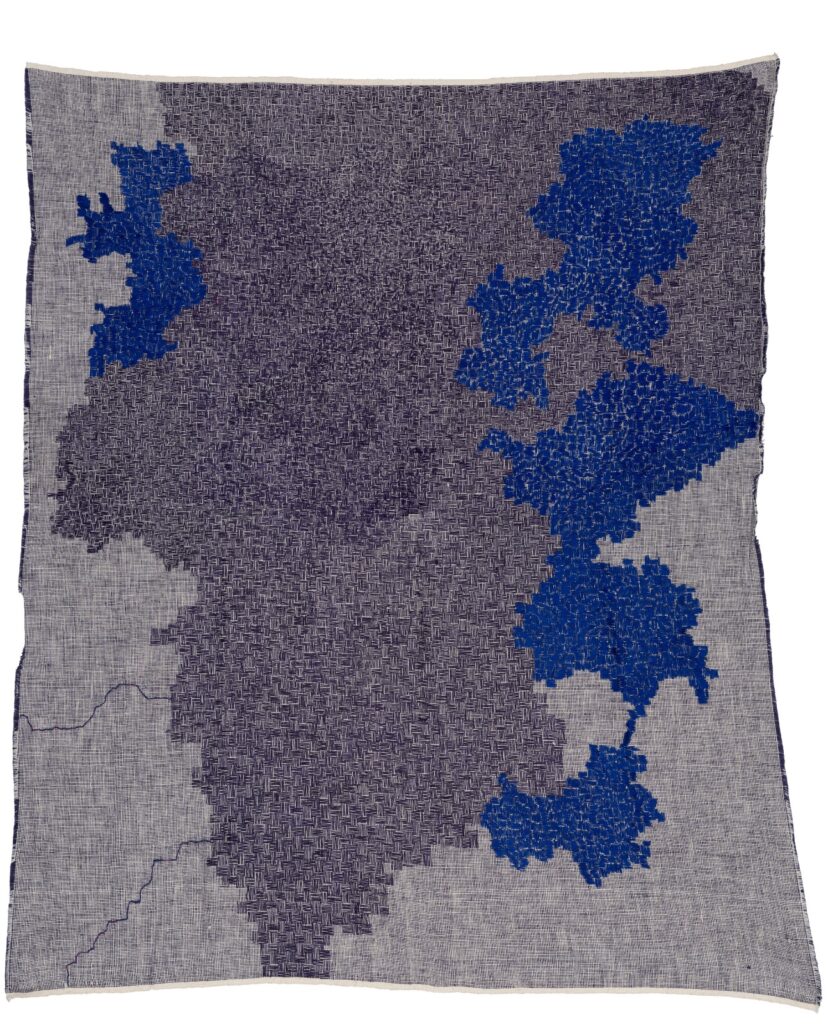

In 2004, I founded FSCA, an art advisory company that has curated thoughtful exhibitions, including one of India’s largest public art projects, the Elephant Parade in 2017–18. That same year, we launched Cultivate Art as a platform to support emerging artists from the Indian subcontinent. At the time, while established galleries represented well-known artists, young talent from institutions like Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda and Srishti in Bangalore had few opportunities for exposure. We aimed to bridge that gap.

Over the past eight years, Cultivate Art has had a significant growth. Many artists we showcased have won major awards and gained recognition internationally. Now, we are opening a permanent space in Bangalore, and this is a major milestone for us. This move was made possible through a kind gesture by my cousin, who has run an antiquities gallery in the heart of the city for 23 years. It’s the perfect opportunity to introduce our artists to a fresh audience, something that’s always been the main motive of our mission.

How is the gallery culture and art landscape evolving in India today?

Now, it has been 20 years that I have been in the art world, and watching it evolve has been nothing short of fascinating. The transformation has been steered by changes in the economy, increased disposable income, and a growing interest in the arts among younger generations.

While legacy galleries like Chemould, Pundole, Dhoomimal, and Delhi Art Gallery have long dominated the space, the last two decades have seen the rise of home-grown auction houses like Saffronart and AstaGuru, helping establish a strong and dynamic art market in India.

What is remarkable is how people without traditional art backgrounds are now creating impactful spaces. One former client of mine, once a travel agent, now runs one of the most interesting international art programs in Mumbai. This shift reflects a broader cultural change, where once many felt intimidated by art or claimed they “didn’t understand it,” there’s now a growing awareness that art reflects politics, environment, and the society. It is less about understanding and more about engagement.

Art has also become more mainstream. Record-breaking sales make front-page news, and thus, it is far more accessible and not just for the elite. The interface between a collector and artist or a gallery has changed so many ways. Technology has played a huge role.

Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and Zoom have transformed how we connect, view, and discuss art globally. You can have Zoom calls with artists living in Brazil so, you don’t have to travel to Brazil to go and see a show. Therefore, one can experience international exhibitions or engage with artists, making the art world more accessible and interconnected than before.

From a collector’s point of view, how have aesthetics and preferences changed over time? What are these preferences and tastes of the collectors?

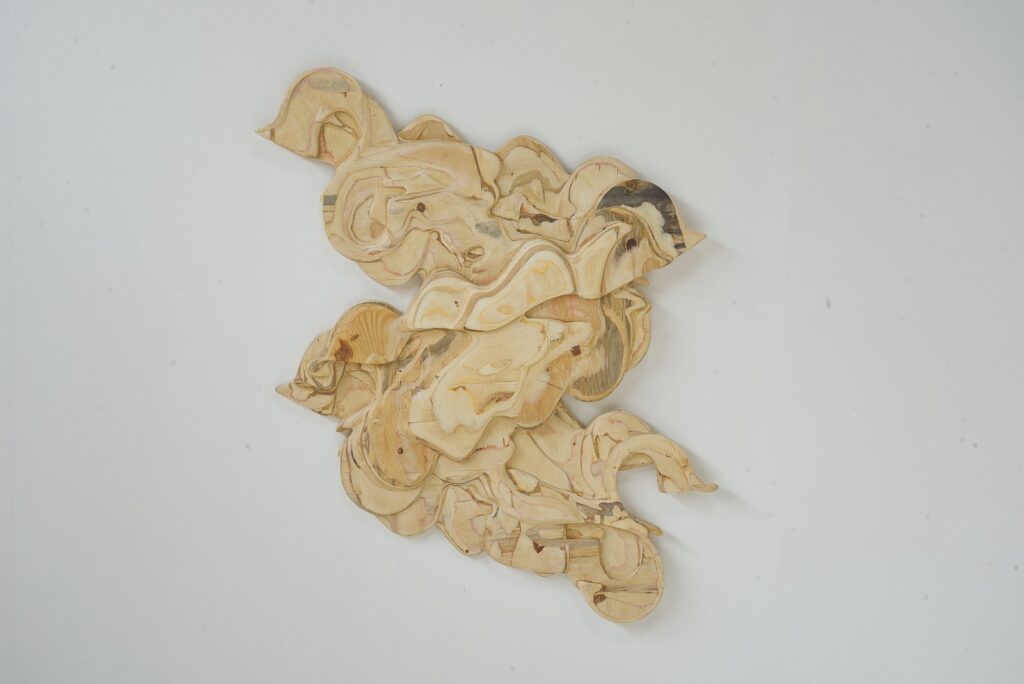

Tastes in art have evolved, but it is the artists who bring the change, not the collectors. Artists themselves have always been individuals who have pushed the boundaries. They have always painted or produced artworks which have always been either reflection of society or very cheeky. During the Renaissance period, many worked at the Church while producing subversive works. Real artists are often mavericks, focusing more on expressing their opinion than on market value.

Each generation brings out artists who are intuitive and reflective of their times. Their work captures specific moments, emotions, and changes in society. So they create from a place of authenticity, rather than responding to market demand. This is the element that makes art influential.

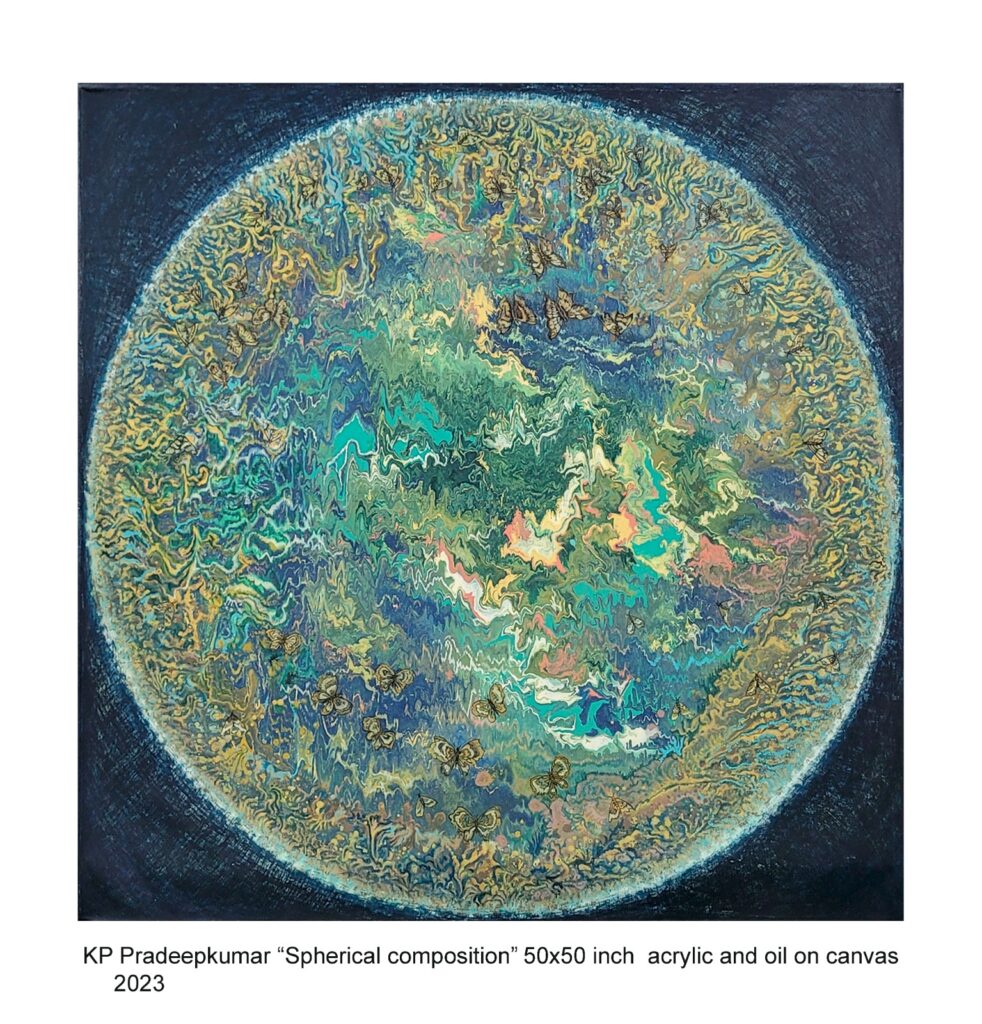

The most exciting thing is the incredible variety of work being produced today. In art, there’s always something for everyone; whether one’s drawn to more traditional forms, serious and detailed pieces, or artists working with technology.

I think there is a lot of artwork out there and a lot of very good artists. A lot of artists are very determined, one of the important qualities of an artist. They have the determination of producing works even if there is no sale.

This is the age of Artificial Intelligence(AI), and we are in the era of generative AI, where it is influencing a lot of artists’ work as well as how the galleries present art. And so, what is your take on this topic, specifically in terms of how the artists are collaborating with AI and tools?

It’s a brave new world, and technology is definitely finding its way into art. One of the interesting aspects of technology for me is blockchain. I have even invested in a company exploring its application in art. It traces provenance, a need of the hour. Blockchain provides a secure and traceable platform to buy and sell art. It is beyond the paper-based transactions, moving towards a more sealed and future-ready system.

AI in art is exciting and fun, and undoubtedly it will play a major role. However, the human touch to art is irreplaceable. Art is meant to move you, and while AI can generate art, it lacks the sensitive quality a human hand produces. This something necessary not just in art, but in fields like medicine as well.

With that being said, there are some challenges as well. Recently, there was a trend on Instagram, the Ghibli Art trend. This trend used the visual language of a Japanese anime artist, allowing people to animate themselves in the Ghibli style. While it being fun, it is very sad. It overlooked the fact that the artist has spent hundreds and thousands of hours making his own visual language, which was then replicated by somebody sitting in some café. It is wrong to consume somebody’s work like that, raising questions about the ethical use of creative artwork in the age of technology of AI.

Was there a particular artwork that caught your eye in your early years and motivated you to pursue in this field?

I learned painting as a child, and that early exposure sparked my interest in aesthetics. I was also drawn to architecture, so there wasn’t one specific artwork that caught my eye. But I would say that visiting major international museums definitely deepened my attraction with art. This is something I now try to do with my own six-year-old, expose him to art from an early age, just like my mother did for me. Those are the impressions that stay with you rather than the ones you get fascinated with at an older age.

In a generation where most of the things have become commercialised, how do you balance your creative vision with the commercial aspects of running an art platform?

It’s always a balancing act between presenting work that can be consumed commercially and work that challenges the viewers in an exhibition. We try to maintain that balance. There have been exhibitions with zero sales, and others that sold out even before opening.

In the end, it comes down to the artworks that speak to us at that moment. For example, there have been artists who have worked at full steam three years ago but may not continue producing that exciting and challenging work. Thus, our focus is always on what feel apt, captivating, and meaningful at that particular moment.