Gender equality is still a distant dream in South Asia even today, writes Upinder Singh in ‘Ancient India’.

Ancient Indian texts consider kingship to be essentially a male preserve; women usually figure as ‘fillers’ when male heirs were unavailable. But women were considered politically relevant by the composers of the Mahabharata and Ramayana. In the Ramayana, Kaikeyi almost succeeds in diverting the royal succession to her son Bharata. In the Mahabharata, the Kurukshetra war is an all-men’s affair, but Draupadi is an active participant in debates among the Pandavas on whether or not to go to war; she is a vocal member of the pro-war party.

The Arthashastra too recognizes women as politically relevant figures. Kautilya takes it for granted that in normal circumstances, it is men who rule. He does not consider women as heirs, but as producers of heirs. However, he envisages the possibility of a woman occupying the throne in times of political transition, for instance, when a king has died or is on his deathbed and the minister has taken over the throne to maintain order and continuity. In such a situation, the options before the minister include putting a prince, princess, or pregnant queen on the throne. Further, while arguing for the superiority of utsaha-shakti (the power of energy) over prabhu-shakti (the power of might), Kautilya states:

Those who possess might—even women, children, the lame and the blind—have conquered the earth by winning over and purchasing those who possess energy.

Kautilya describes female guards (along with eunuchs, hunchbacks, dwarfs, and hunters) as part of the protective security cordon around the king, an important function, considering that Kautilya’s king lives in constant fear of assassination. But he has much more to say about how women pose serious threats to the king’s life. In contrast to the depictions in Sanskrit kayva, in the Arthashastra, the antahpura (harem) is a place of danger.

The king can protect the kingdom only when he is protected from those close to him and from enemies, but first of all from his wives and sons.

The royal family is not a happy family. Lovers, queens, and sons are ambitious, ruthless, and dangerous. To drive home his point, Kautilya cites several instances of kings who were killed by their queens.

Of course, the Arthashastra is a normative text and describes a potential state. To what extent do women appear as active political agents in the political history of ancient India? Across the centuries, the narrative of ancient Indian political history seems to be a story of kingdoms and empires ruled by men. Women figure as pawns in matrimonial alliances and as producers of heirs. But there is evidence of women of royal households exercising power and authority.

The Satavahana and Ikshvaku kings used matronyms (that is, they were named after their mothers) and inscriptions show that women of the royal family were influential figures. The political importance of matrimonial alliances in ancient India is reflected in the portrayal of queens on certain Gupta coins and the mention of queens in Gupta genealogies in inscriptions. But there are also instances of powerful queens in ancient India who exercised political power directly.

In the fifth century ce, a marriage alliance cemented the relationship between the Guptas who held sway in the north and the Vakatakas who ruled in the western Deccan. The Vakataka ruler Rudrasena II was married to Prabhavatigupta, daughter of the Gupta emperor Chandragupta II.

Vakataka inscriptions reveal that Prabhavatigupta exercised political authority during the reign of her husband. When he died, his sons Divakarasena, Damodarasena, and Pravarasena were minors, and Prabhavatigupta became de facto ruler. Divakarasena did not live long enough to ascend the throne, but his younger brothers Damodarasena and Pravarasena (II) did, and the queen mother continued to hold the reins of power. Prabhavatigupta made grants of land and her inscriptions give the Gupta genealogy before that of the Vakatakas.

There were other women who ruled. In the Eastern Chalukya dynasties, Vijayamahadevi became ruler after the death of her husband, Chandraditya. The Kadamba queen Divabbarasi ruled till her minor son attained majority. Several queens ascended the throne in the Bhauma–Kara dynasty of Orissa—Prithivimahadevi (also known as Tribhuvanamahadevi), Dandimahadevi, Dharmamahadevi, and Valkulamahadevi. While these women became rulers due to the absence of a male heir, Prithivimahadevi’s accession was probably also linked to the influence of her father, who belonged to the powerful Somavamshi dynasty.

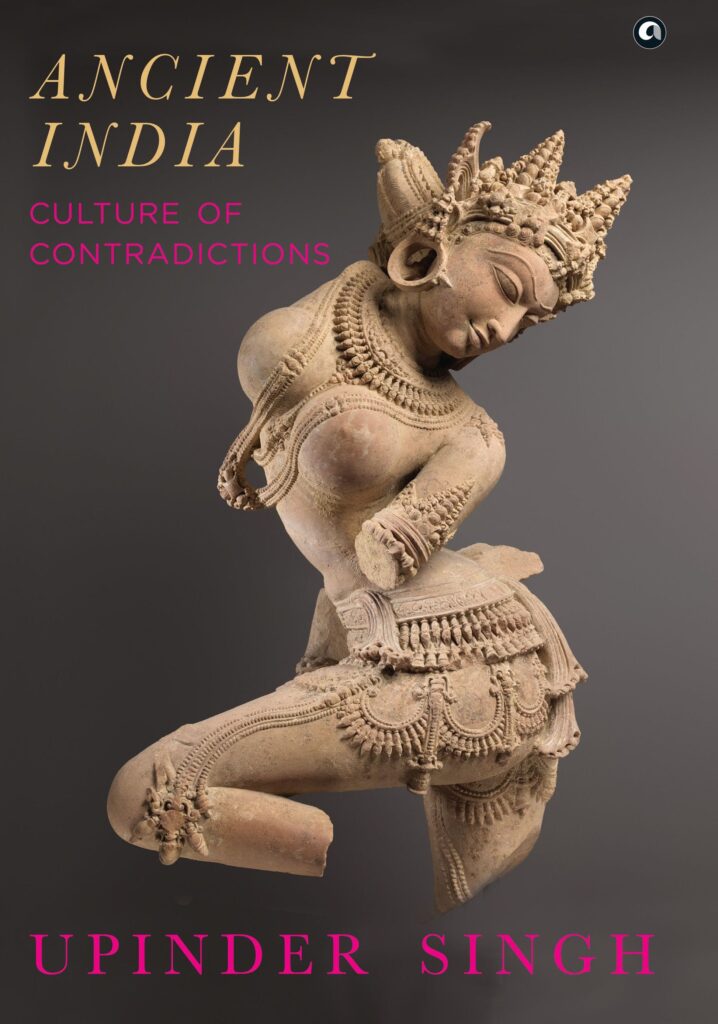

Book details:

Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions

By Upinder Singh

Aleph Book Company

280 pages; Rs 799

Publication date: 5 October 2021

Kalhana’s twelfth century Rajatarangini mentions three women rulers of Kashmir—Yashovati of the Gonanda dynasty, Sugandha of the Utpala dynasty, and Didda of the Yashaskara dynasty. Didda had the longest and most eventful tenure, exercising political power continuously for almost fifty years.39 She was influential during her husband Kshemagupta’s reign, was regent for her minor son Abhimanyu, and in 980–81 ce, ascended the throne to rule Kashmir in her own right. Kalhana states that Didda was aided in her rise to power by the minister Naravahana, who established her rule over the entire kingdom and made her comparable to Indra.

She, whom none believed had the strength to step over a cattle track—the lame lady—traversed, in the manner of the son of the wind [Hanuman], the ocean of the confederate forces.

Didda founded towns and built temples and monasteries. Kalhana describes how she killed her son and three grandsons before ascending the throne. Although killing rivals must have been routine in politics, Kalhana disapproved of a woman doing such deeds. He describes Didda as merciless, lacking in moral character, and easily swayed by others. He thought that this was partly because of the fact that she was a woman:

Even in the case of those who are born in high families, alas! The natural bent of women, like that of rivers, is to follow the downward course.

Nevertheless, Kalhana did acknowledge Didda as an important figure in Kashmir’s political history.

Across the centuries, the idea of the feminine as embodying fertility, auspiciousness, and plenitude coexisted with the idea of women as having negative and destructive potential. The ambivalence towards women had multiple roots—attitudes towards the woman’s body, sexuality, and procreative potential; the patrilineal obsession with the production of sons; the need to control women’s behaviour in order to perpetuate the caste system; and the perception of female sexuality as a threat both to male celibacy and virility.

In the religious sphere, although the central foci of veneration and religious authority remained male, female deities had a strong presence. The story of goddess worship in India is not one of diminishing significance, but of increasing vibrancy and importance. ‘Goddess culture’ formed a strong, continuing aspect of popular belief and practice, cutting across sectarian identities and divides. From the nineteenth century onwards, the nation too has been visualized as a goddess, Bharat Mata.

Even today, in villages across the length and breadth of India, apart from the female deities known from texts, goddesses of childbirth and disease are worshipped to provide succour for everyday concerns and anxieties.

However, goddess worship did not and does not translate into empowerment for real women. Within patriarchal social structures, women have always faced different degrees of subordination, depending on their class and caste and on the prevailing kinship structure. Many texts indicate increasing efforts to control and confine women within the bounds of the family and household. But the continuing attempts to control and discipline women suggest that norms and rules were not always followed and hence had to be hammered home, century after century. The statements about the proper behaviour of women and wives in many ancient texts sound depressingly familiar and similar to attitudes prevailing in India today, but then as now, there were women who did not conform and who dared to strike their own path.

Male-dominated social and political systems offer certain spaces within which upper-class women can exercise their agency in various ways, but these spaces are very narrow for non-elite women, whose experiences of subordination and oppression are qualitatively different and are largely undocumented in the sources of ancient times. Even today, in the countries of South Asia, although some women have managed to break through the glass ceiling and have made it to the top of their professions, although there have been women presidents, prime ministers, and political leaders, gender equality is still a distant dream. The golden age for Indian women does not lie in the past but in the future.

(Excerpted with permission from Aleph Book Company from the book Ancient India: Culture of Contradictions)

Write to us at [email protected]