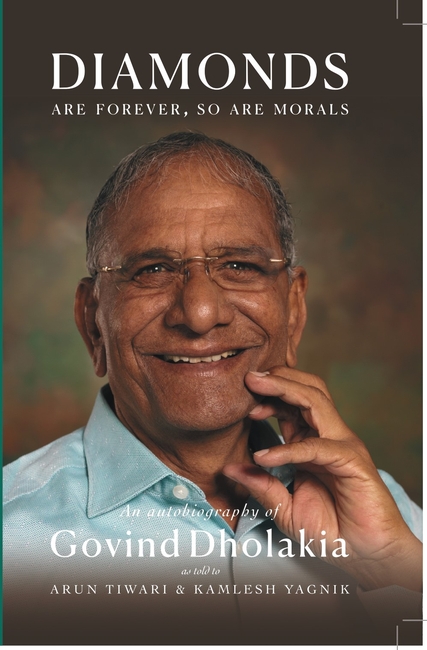

How Govind Dholakia polished his skills in the diamonds crafting business

When I arrived in Surat in 1964, there were around 200 people in the diamond cutting and polishing factories and the population of the city was 300,000. Diamonds are the purest matter on earth. They are formed in the great depths of the earth, under intense heat and immense pressure for millions of years and come out through volcanic eruptions. They are rare and therefore, highly valued. Once the diamonds were cut to a good shape and polished, they became a bundle of light and then were acquired by the rich and powerful of the times. Antwerp in Belgium had been the epicentre of the diamond trade in the world.

After India became independent and wealth started coming to the industries and businesses, a market for diamonds was created in Bombay, Surat and Navsari. People started selling them to other places in India and even began exporting them. Some Indian businesspersons started buying rough diamonds in Antwerp and started making money by getting them polished in Bombay and reexporting them at significantly higher prices. H. H. Zaveri, H. B. Shah and Mohandas Raichand were amongst the pioneers of the diamond business in India…

Penguin Enterprise; 380; Rs 699

Publishing date: 24 March 2022

…I joined Gordhanbhai Khadsaliya’s diamond factory at Daliya Sheri as an apprentice. Arvindbhai Dabhoiwala gave me a broken porcelain pot and taught me how to grind that to a shape. In two weeks, I acquired all necessary skills under his watchful eye. It was 20 April 1964, when Arvindbhai gave me a rough diamond to work with.

An industrial-quality diamond is mounted at the end of the stick, and the stick is held by hand against the rough gem diamond, forcibly contacting the stone to slowly brute (scratch) the material away. Without getting nervous or overwhelmed by the difference in the value of a porcelain piece and a rough diamond, I polished it as per his instructions and to his satisfaction. It was very satisfying to see the lower-quality diamond scratching the gem diamond stroke by stroke to remove diamond dust and small fragments until the crude shape was accomplished.

My apprenticeship with Arvindbhai lasted for two months; I spent the next four months with Ishvarbhai Dholakia for acquiring additional skills in cutting and polishing. There was no stipend whatsoever paid to the apprentice. My first job was in the factory of Hirabhai Vadiwala. I earned Rs 103 in my first month’s work of polishing a rough diamond…

…I soon learnt how to work on a bruting machine and joined the factory of Laljibhai Kheni at Kumbhar Street, Galemandi. Though Bhimjibhai and Bhabhi supported me well, I started staying in a little portion of the common house meant for the workers. My impeccable habits and religious bent of mind made my colleagues and even the elders call me ‘Govind Bhagat.’ I did not protest. I secretly felt pleased about it.

It was at Laljibhai’s factory that I met Bhagwanbhai Patel and Virjibhai Godhani, ten years elder to me. I developed an unexpressed comfort zone with Bhagwanbhai and Virjibhai. It was a gradual process of mutual respect, affection, and appreciation, spread over many years.

Read: Gopichand’s Words of Wisdom

However, everything was going well, my heart was yearning to start my own little business. I wanted to be a leader and not a follower. To my hormone-charged young mind, a leader was meant to stick his neck out on a bold course of action even as the rest of the world wondered in awe. The only way ahead for me was to stand out from the crowd and to stand for something special.

Laljibhai Kheni blessed my aspirations but advised me to understand the business in depth before getting into it. ‘Business is like a one-way street; you never return once you start,’ he told me. Later, when I was reading Satyana-Prayoga Athva Atmakatha, I realized the soundness of Laljibhai’s advice. Gandhiji was 46 years old when he returned to India.

Read: Shivarama and Leela Karanth: A Life History

Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who Gandhi regarded as his political mentor, had advised him to remain silent for one year during which he was to try and visit as many parts of India as physically possible, and meet as many people as he could, and acquaint himself with their problems. This was what Laljibhai was telling me. I decided to obey him most sincerely. I developed a habit of walking long distances, mostly in the early morning. It was my own peculiar way of meditating. Later, I learnt that walking meditation is indeed a wholesome practice called Kinhin in Buddhism. I used to follow different roads to walk without any purpose or design.

Excerpted with permission from Penguin Enterprise from the book Diamonds Are Forever So Are Morals: Autobiography of Govind Dholakia

Write to us at [email protected]