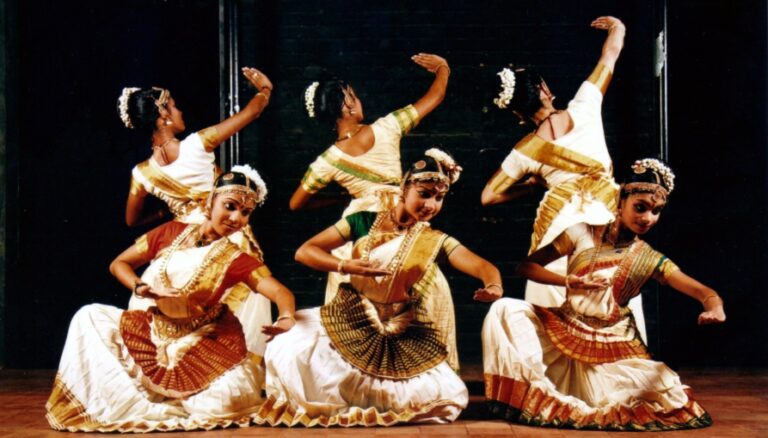

The present day Mohininyattam is a beautiful combination of the desi aspect of Kerala and the devadasi dance form that came from outside.

Hinduism started evolving into a religion post the age of Adi Shankara, with temples being the centres of cultural and spiritual practises. In Kerala, some of the temples started adopting Hindu gods into temples that belonged to Jainism or Buddhism. With the arrival of Brahmin clergy, importance of ritualistic practices grew over a period of time. Tantric practices that originated in different parts of India including West Bengal, Kashmir and Kerala played an important role in shaping some of these rituals. The concept of Dēvadāsis (temple dancers who are dedicated to the temples supposedly as consorts of the deity) perhaps originated as part of the Tantric rituals. Panchamakaras form an important part of the Tantric rituals. These are the five transgressive substances used in Tantric practice. This includes madya (alcohol), mamsa (meat), matsya (fish), mudra (gesture) and maithuna (sexual intercourse). The devadasi tradition is believed to have originated from the requirement for maithuna, and is thought to be as old as the third century BCE with some references in Kautilya’s Arthashastra.

Mohiniyattam and Devadasi tradition

The Dēvadāsi dance tradition which developed through the temple dancers is of great significance to dance forms of India. Bharatanāṭyaṁ in Tamil Nadu and Odīssi in Orissa (Odisha) have drawn from the tradition of Dēvadāsi dance before growing and developing as a classical form. Traditions like Kuṟatti which was part of Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ till it reached the Kalāmaṇḍalaṁ, reflect the regional folk traditions of the form. There are temples even today where the Kuṟatti traditions remain. Kuṟattiyāṭṭaṁ of Tripunithura Pūrṇatrayiṣa temple and Irinjalakuda Kūṭalmāṇikyaṁ temple are examples of this. In the case of Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ, the regional traditions/cultural background of Kerala have had influences on the form. Scholars believe that the present-day Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ is a beautiful combination of the regional aspects of Kerala and some of the Dēvadāsi dance forms which came to Kerala later on.

References in the purāṇas show that the custom of dedicating maidens to the deity in the temple was practised in India even from very early times. The chief duty of these Dēvadāsis as they later came to be known, was to be in charge of the music and dance aspects of temple rituals. It is a known fact that in India from the early days, the dancing and singing of Dēvadāsis was an integral part of temple worship. There is evidence to show that Dēvadāsis were attached to temples in various parts of India like Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Rājasthan, Gujarat, Bengal, Orissa and Kashmir.

References in ancient texts

The Śaiva section of Hinduism seems to fancy the Dēvadāsi custom more than any other sect. The Shiva Purāṇa clearly lays down that when Shiva temples were built and endowments were made for the conduct of the daily rituals, provisions had to be made for the gifting of damsels to the temple, well-versed in dance and song. The details of their dedication ceremony are described in Linga Purāṇa. It also hints that this kind of oblation is most pleasing to Shiva. There is ample evidence to show that along with the construction of Shiva temples, Dēvadāsis were also offered to the temple. History records the fact that when Raja Raja Chola built the Bṛhadīśvara temple in Tanjore in the ninth century CE, he gifted 400 Dēvadāsis as well to the temple.

Halāsya Mahātmyaṁ written in praise of the Halāsya temple refers to a danseuse by name Hēmanātha, a Shiva devotee:

“Daily dancing at the close of temple rites,

A danseuse is there, devoted and bright;

She serves the devotees of Shiva

And dances when the pūja ends”

From this, it is clear that dance was an important factor in the worship of Shiva. The first items in Bharatanāṭyaṁ called alārippụ and in Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ known as cholkeṭṭụ are considered to be sacred dance patterns for Lord Shiva. A stuti or praise of Shiva towards the end of the text used for cholkeṭṭụ Mōhiniyāṭṭaṁ confirms the similarity. At the beginning of the cholkeṭṭụ, there is a Dēvi stuti (praising Mother Goddess) and towards the end, a Shiva stuti (praising Shiva). This Dēvi stuti must be the continuation/remains of the ancient tradition of the Mother Goddess worship in Kerala.

Read Part 10

(Assisted by Sreekanth Janardhanan)