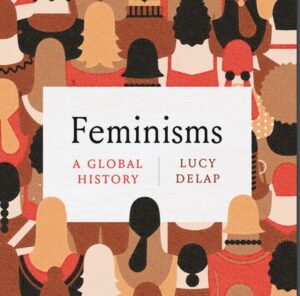

Exactly two years ago, Lucy Delap deconstructed the myth that feminism is all about euro-centrism in her marvellous work Feminisms: A Global History

“Feminism is not a philosophy, or a theory, or even a point of view. It is a political movement to transform the world beyond recognition.”

— Amia Srinivasan, The Right to Sex.

Feminism has gone through a major wave of transformation where its aim of achieving gender equality has been modified and remodified on a global-level.

Spanning an exceptional range of concerns from sexual autonomy to the right to vote, feminism has cross-border and trans-national impacts and it has been hailed and equally attacked in academic discourse.

Concerning a wide variety like that of Black feminism, cultural feminism, ecofeminism, Marxist and socialist feminism and so on, this movement has academic, social and cultural connotations which are aimed at solving disparities between man, woman and those who are outside of this gender binary.

What historian Lucy Delap has achieved through Feminisms: A Global History is a brief history and the current state of feminism where it is explicating the ‘end state’ of gender equality.

To her credit, Delap, who teaches at the University of Cambridge, has deconstructed and enunciated the wrong assumption that feminism is after all an anglophone mainstream thought and practice.

Mosaic feminism

She has lucidly detailed the roots of feminism being ever present and active among the coloured and the underprivileged sections of society throughout the world.

Her work is an exuberant analysis of the contributions of women leaders and associations who are at the forefront to shed light on the injustices of gender. ‘Ideas’ of patriarchy, sexism and intersectionality get special attention in Feminisms: A Global History.

However, Delap has elucidated its limitations, blind spots and complexities. Feminisms: A Global History is a detailed narration of feminist inspirations, its sonority across different eras and generations and the colossal designs that promoted ideas like that of ‘woman question’, ‘women’s right’ and their final emancipation.

Delap has diffused the notion of a ‘mosaic feminism’ where fragmented ideas render this movement with spectacular patterns and designs which impart different meanings while reading it from close quarters as well as from afar.

The potency of ‘dreams’ has been an area of discourse in the literary and psychoanalytic fields; and Delap has explained the creative power vested in dreams in fulfilling and directing the aims of feminism.

‘Ladyland’

Right from gender erasure to the establishment of a gyno-centric utopian society, many feminists all over the world have envisioned an ideal world where equality and justice prevail. They even foresaw the promulgation of an altogether new ‘language’ that was entirely different from the language forced upon them by men.

Delap, who is also a fellow of Murray Edwards College, is of the opinion that such dreams of a ‘Ladyland’ and ‘Herland’ are situations of uneasy utopianism and it directs towards the strained and disputed feelings that are associated with perceptions of a different life.

The realization that sexual differences are not something natural but forced upon society in various shapes across time and space has evidently become advantageous for feminists while fashioning their ideas for a better tomorrow.

The social and the political structures that maintain and balance these ideas of gender have paved way for the ultimate realization that sexual differences are capable of taking different forms in different times.

Androcentric language

Explaining the concept ‘Turk Complex’, the author describes the male attitude towards women and the patriarchal dominance and the egoism and narcissism that accompany it.

The major solution that many of the feminist movements all the over the world single-mindedly opted for was a re-working of the androcentric language and the names like Julia Kristeva and Helene Cixous stand for discarding the ‘phallocentric’ formats.

Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own nurtured the idea of a feminist ‘space’. It heralded the rightful space that a woman must acquire in matters of worship or work to produce spaces for security and asylum. But, one of the major themes of feminism — spatial autonomy — has never been an achieved milestone. The same goes true when it comes to non-harassing spaces for women.

Even religion and ethnicity too play prominent roles, so that the acquisition of feminist spaces is not devoid of further policing and boundaries.

Feminist things

The material culture of feminism has been idealized throughout history through ‘objects’, from brooch pins to posters. The popularity of ‘feminist things’ to an extent accelerated the spread of feminism. It reached a stage that a simple thing like a hat pin to a full-fledged poster could take this movement to greater lengths.

The introduction of such objects made it possible for feminists to touch or buy or wear feminisms though their commodification resulted in many controversies. Is there something called a ‘feminist look’? Fashion and looks have been a contested area where female bodies are symbolically and physically strained and marked for gaze and desire.

In Delap’s own words, “…clothing has been a site of feminist challenge and subversion.”

The role of female bodies and fashion within feminism has been a debated area, subverting the dressing norms and also about who is the ‘spectator’.

By subversive looks, they meant gender non-conformity and dressing to please themselves and not men. But there were those among the feminists who disagreed with politicizing dress as a cultural site.

Politics of emotions

The author is of the opinion that a feminist look can span from a beauty tiara to a burlap sack as long as it justifies the needs.

The politics of ‘emotions and feelings’ has been an integral part in rethinking the gender structure and this gave way to anger first and later into love and motherhood feelings.

The pursuit of happiness has been the core of the feminist agenda and later as a source of power, too. The author describes feminism as ‘passionate politics’ where strong feelings are disrupted and re-generated pain into gain.

The ‘resting bitch face’ is one of the many ideas that resonates with feminist feelings. The expressions of ‘self-love’and the emotions of happiness are all molded by the cultural context in which they are produced and expressed. It is through these contradictory emotions that feminisms all over the world are withheld through numerous historical discourses.

Opposing oppression

While re-working on inherent emotions like hope, anger, love, shame and grudge, many feminists worldwide re-channelled and effectively diverted their feelings into meaningful actions.

Spanning a vast spectrum from public-speaking to saying ‘no’ to intimate things, feminism as a movement has incorporated various actions like stone-pelting, violent demonstrations, strikes, picketing and, in worst case situations, even bombing as their tool in making their actions heard and seen. ‘Bra burner’ is one such action where women are encouraged to walk around without a bra, which they associate with male domination and patriarchy over female bodies.

Delap further explains how ‘music, songs and chants’ have become a profound ingredient in opposing oppression. Songs created by championing women detailed womanhood as sites of friendship and enjoyment as well as against rape and harassment. It is this music and songs that helped activists to create communities.

They helped feminists with fund-raising, satirizing opponents, and claiming the spaces where they are unwelcome earlier. Delap’s Feminisms: A Global History is a concise history of feminism where the attention has been diverted to diverse and plural elements while sidelining euro-centrism.

It is a mutual politics of knowledge established by deciphering, acclimatizing and re-printing. Feminisms: A Global History is a wonderful narration about the ‘entangled histories’ where the aim is to reach an ‘end state’ of gender equality.