Swiss Indologist Alice Boner’s enthusiasm for Kathakali triggered the Kerala art-form’s popularity across the West since the 1930s. She remains largely forgotten amid the 90th anniversary celebrations of Kalamandalam, the dance-theatre’s premier institution.

Of all the performing art-forms in India, Kathakali has been of particular attraction for foreigners from the days Kalamandalam came into existence in 1930. Crucially, they came to know about the dance-theatre the same year through Alice Boner, the renowned Indologist who discovered Kathakali for the West.

An internationally acclaimed painter and sculptor, Alice (1889-1981) was an outstanding scholar of Indian sculpture and temple architecture. The Swiss lady made the Hindu pilgrim centre of Varanasi upcountry her permanent home in 1936. The Government of India, in recognition of her contributions, conferred her with the top civil honour of Padma Bhushan in 1974.

Alice’s quest for the arts and culture of other countries became strong during a training she underwent in visual arts — first in Munich and later in Brussels. She went on to visit Tunisia, Monaco and a few other places, but her dream to visit India remained unfulfilled for a while.

The desire to see India became stronger when Alice got the chance to read the works of English art historian EB Havell and a few other Indologists. Around that time, she happened to watch a performance by dancer Uday Shankar in Zurich in 1926. The sculptural beauty of the choreography captured her attention. It appeared to Alice that Shankar had breathed life into the sculptures in the temples of India about which she had read during her childhood. Three years later, she got another opportunity to watch Shankar’s performance — at Paris in 1929.

Meeting Shankar

Soon she met Shankar. The first rendezvous itself helped the two develop a strong bond between them. While in Paris, Shankar told her that he was disappointed to perform to recorded music. For his upcoming programmes in Europe and the US, Shankar wanted to form a group of Indian musicians so that he could perform to their live music. To realise it, she planned an India trip with him. This journey also had Uday’s younger brother Ravi Shankar, who was to later turn a celebrity sitarist.

Alice and Uday first landed in Madras. In 1930 summer. They came to know about an upcoming Kathakali festival in the neighbouring state of Kerala. Braving pre-monsoon rains, the two reached the pilgrim town of Guruvayur on May 9. They saw hectic preparations for the four-day event that was to feature stalwarts. The programme was part of a lottery-ticket dip poet Vallathol Narayana Menon had organised with his cultural lieutenant Mukunda Raja. The aim was to raise funds to establish Kerala Kalamandalam, a training institution for Kathakali. Alice could gather that the dance-theatre was on the verge of extinction owing to a lack of patronage. The feudal lords, who traditionally promoted it, were facing a decline in their finances and clout.

For four days in succession, the duo watched Kathakali till dawn sitting on the floor right in front of the stage. The synopsis of the plays prepared in English was of much help to follow the stories. Alice, being a gifted painter, made sketches of the characters on stage. She jotted notes in a diary. The duo returned on May 16 with the sweet memories.

Series of sketches

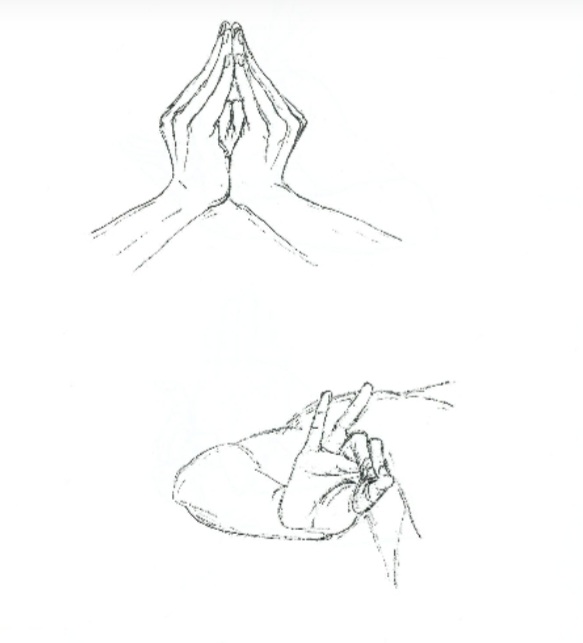

Four years from there, Alice’s insatiable infatuation for Kathakali brought her back to Kerala. In 1934, when Kalamandalam had completed four years at a small palace owned by Mukunda Raja at Ambalapuram near Thrissur. There, she got a ringside view of the Kathakali training — by maestro Kunchu Kurup. She learnt the 24 basic mudras (hand gestures) from Kavalappara Narayanan Nair, and made sketches of them as well.

In fact, Alice drew vignettes of all what she witnessed there. The graphic representations of the costumes and make-up of that period have added archival value today. Further, her diary is an authentic record of the observation of the first Westerner and, therefore, unprejudiced. It was she who compared Vallathol to Bengal’s Rabindranath Tagore who had established Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan to promote the arts.

Alice wrote to Russian theatre actor-director Michael Chekov a series of letters about her cultural experiences in Kerala. She also sent him the self-drawn sketches. These served to a great extent in Kathakali gaining popularity across Europe.

Alice also wrote to Tagore, who already knew the greatness of Kathakali. On his request, Vallathol sent Kelu Nair of the first batch of Kalamandalam to Santiniketan to teach Kathakali. In return, Tagore sent singer-actor Santidev Ghosh to Kalamandalam for further training. Soon, on Alice’s request, a Kalamandalam team was invited to Santiniketan to perform. A new report on this appeared in Amrita Bazar Patrika, winning international fame for Kathakali. Tagore confided to Alice if his Nobel-winning Gitanjali earned him recognition as a poet among Indians, so would be the case with Kathakali if it won the white people’s praise.

Alice was the first ambassador of Kathakali to the West. And the first European friend of Kalamandalam. Even as the premier cultural institution is celebrating its 90th anniversary now, Alice finds no public mention.

(Pictures courtesy , “Alice Boner on Kathakali” published by Alice Boner Foundation)