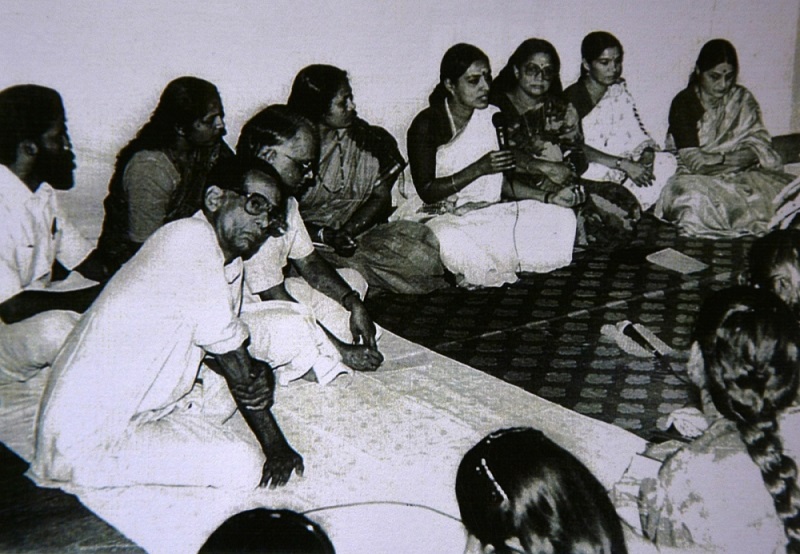

Kavalam Narayana Panicker, a guru nonpareil, strode like a colossus over the cultural arena of the country for around five decades.

“Sangeetham api sahithyam/Saraswatya sthana dwaya

Ekam aapaada madhuram/Anyad aalochanamrutham”

(Sangeetham and sahithyam are the two breasts of Goddess Saraswathy. While one is entirely sweet, the other is nectar to the thinking mind)

Ever since I heard about Kavalam Narayana Panicker during my younger days and further came into personal contact with him during the 1980s, the above sloka has flashed on my inner eye and it continues to do so even now five years after he has left us on this day (June 26). Why?

Over the past three decades of my stint as an art journalist, I had the privilege of interacting with celebrities of all hues belonging to the artistic and literary fields. But I have met only one who is equally proficient in both Sangeetham and Sahitya. That was Kavalam. In this sense, he was a nonesuch personality. And what made him a legend even during his own lifetime was nothing else.

Kavalam was a Guru nonpareil. Not only for the enlightenment of his disciples but also in terms of the wider definition of the title. One attains the status of Guru only when he/she is capable of propounding a new doctrine, a new style or a new school of thought. The form of theatre he evolved – ‘Theatre of roots’ (‘Thanathu Natakam’) – and the style of Mohinyattom based on the esoteric music and rhythms of Kerala, Sopana sangeetham, are living testimonies of his immortal contributions. If a disciple has been described as one who practices and disseminates the style of his/her Guru, he was blessed with many. Much has been deliberated on his contributions to theatre.

Innumerable are the productions that are striking paradigms of an amalgamation of Margi and Deshi traditions of the country. For the same reason, they appealed to the pan-Indian audience for whom it was a hitherto unknown experience. Profound and discerning knowledge of Natyashastra did not prevent him from delving deep into the ‘Upa roopakas’ especially those that belonged to Kerala. So, naturally, even his Sanskrit plays bore an imprint of the essential cultural traits of Kerala.

Aesthetically rich rhythms

I had the privilege of interacting with many of his disciples in theatre, those who were under his umbrella for more than decades. Interestingly, they included film actors as well. All of them had vouched for Kavalam’s ingenuity of banking on rhythms for theatre training. Initially, they were all surprised when he made them learn vaytharis of rhythms, coming as they were from conventional theatre backgrounds. But as the training progressed, they realized how the practice of these syllables made their movements aesthetically rich. Herein lies the secret of his technique – the relation between music, rhythm and movements.

The rudimentary function rhythm is to stimulate and regulate movements. Moreover, it provides a compact structure to it when performed in a group or solo. Combined with music, rhythm accentuates the intrinsic parts of sahithya as well. The dialogues in his plays are highly stylized and entail cadences of the voice of the actors. This is a basic tenet of the technique of communication; since more than sahithya the quintessence of the message is delivered more effectively through the cadences.

Kavalam was an authority of this technique which was rarely comprehended and employed by dramatists of his times. Many eyebrows were bent when he introduced this unique approach in his plays initially. But it took some time before the protagonists of conventional theatre could realize its efficacy. The interrelationship between music, rhythm as employed in theatre made his plays a class of their own.

Sopanam style of Mohiniyattam

Kavalam’s obsession for Sopana Sangeetham springs from this realization too. As different from other genres of music, Sopanam is intrinsically ‘Thouryathrikam’, as it embraces geetha, vadya and nritta. The vaytharis of Edakka – a musico-percussion instrument which Kerala alone can boast of – instigates movements even in a layman. And admittedly, these movements are marked by their extreme grace. Small wonder then that he found it more suitable to Mohiniyattam, the lyrical dance of Kerala origin.

Kavalam’s foray into Mohiniyattam happened at a time when it was at the receiving end of criticism from the non-Keralite dancer fraternity, inviting opprobrium like ‘poor cousin of Bharatanatyam’. But they were not to blame as the style that was revived at Kerala Kalamandalam and the students who passed out from the institution right from the 1930s, adhered faithfully to the Bharatanatyam repertoire performed to Carnatic music.

Naturally, he exploited the potentialities of Sopana sangeetham to attribute to Mohiniyattam an identity of its own indigenous to Kerala. This is vouched by his observation, “We have a rich popular tradition, preserved and practised in a vibrant and colourful variety of musical forms, dance and theatre. They have been my sources”. While the swaying movements typical of the lasya-rich dance form could be enriched by the style of singing or rendition, numerous rhythms further could be explored to delineate the varied moods of the composition.

While many dancers across the country were fascinated by this exceptional style, it was only Dr Kanak Rele who could comprehend the inherent beauty of his school. Her association with Kavalam yielded alluring results as reflected in the myriad productions of Nalanda that have captured the imagination of rasikas, critics and dancers at the national level. Many are young and promising dancers with strong academic background and training in the conventional style of Mohinyattam who have researched extensively into this style and have notched PhD from different universities. The poetic finesse of his compositions was a major attraction for this class of dancers to incorporate them into their repertoire. So much so, today Mohiniyattam performances on any stage hardly take place sans at least a couple of his works.

A scholar of great repute

Kavalam was undoubtedly the only scholar who was conversant with the cultural ethos of Kerala. Not only was his knowledge of the nuances of the wide spectrum of performing arts ranging from the Sanskrit theatre of Koodiyattam to the myriad folk art forms deep, but he could further demonstrate practically their intricacies as well. Also, he could identify himself with their practitioners for whom he was a patron. He had a special consideration for Ramamangalam, the native village of the legendary musician Shatkala Govinda Marar.

When the Shatkala Govinda Marar Smaraka Kala Samithy decided to produce the Govinda Pancha Ratnam in Mohiniyattam, he was consulted to verify the authenticity of the compositions. A few months before his death, he made discreet enquiries about the temple at Ramamangalam where Govinda Marar used to present the ‘kottippadi seva’. Perhaps he was writing on the contributions of this hamlet in the music and percussion. He once asked me whether it is possible to send a Kudukka Vina artiste to accompany a production of Mohiniyattam he was choreographing!

Kavalam was the first non-bureaucrat secretary of Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi during 1961 -1971. In this capacity, he gave shape to the style of functioning of the institution. Later he adorned the chairmanship of the Akademi twice. But for him, Koodiyattam, the age-old Sanskrit theatre and its legendary maestros like Ammannur Chachu Chakyar, Mani Madhava Chakyar, Ammannur Madhava Chakyar and Paimkulam Rama Chakyar would have been lost in the oblivion. The film he produced on Mani Madhava Chakyar and the interview with Chachu Chakyar are treasure troves for posterity. Koodiyattam Kendra in Thiruvananthapuram was his brainchild during his tenure as Vice Chairmanship of Sangeet Natak Akademi, Delhi. Distressingly, he was totally disappointed towards the end of his life that the institution failed to attain the goals he had envisaged.

Kavalam strode like a Colossus over the cultural arena of the country for around five decades. While the Akademis, both State and central, honoured him with the highest encomiums, the government of India conferred on him Padmabhushan. He was the only scholar to be honoured with a Fellowship by the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi and Kerala Sahitya Akademi. Only a couple of non-performers have been awarded the much-coveted national award Kalidasa Samman and Kavalam was one of them.