In the first part of the interview, we discussed how Nirmala Paniker recounted her 1970s research linking Mohiniyattam with Kerala’s female performance traditions, especially Nangiarkoothu. She shared insights from Mani Madhava Chakyar and Kochukutty Nangiaramma, highlighting her efforts to revive and document this ancient, fading temple art form. In this second part, she highlights her research collaborations with her husband G Venu, and her association with Ammannur Madhava Chakyar’s lineage

In the last part of this series, we talked about your introduction to Nangiarkoothu through your interactions with Mani Madhava Chakyar and Kochukutty Nangiaramma in the 1970s. Did the conversation with Kochukutty Nangiaramma inspire you to take the art form seriously?

Yes, it motivated me to learn more about the art form. My research studies, which began in the early 1970s, gained clear direction by 1979. By this time, Shri G. Venu had become my life partner and had established Natanakairali, an institution dedicated to reviving the withering art forms of Kerala. At that time, Natanakairali’s key focus was on Koothu and Kutiyattam of the Ammannur tradition. When I joined Natanakairali, I added a research wing focusing on the dance and theatre traditions of Kerala’s women. Nangiarkoothu, Mohiniyattam, and Thiruvathirakali became our key focus areas. We later named the female wing Natanakaisiki.

Interesting. It seems your partnership in life also extended to your research interests. Did you and Venuji work together on these pursuits?

Yes. G. Venu, popularly known as Venuji, was a lecturer at the School of Drama in Thrissur when we got married. However, he soon decided to resign and move to Irinjalakkuda to dedicate himself entirely to the study of Kutiyattam. He was determined to preserve the idiom of Guru Ammannur Madhava Chakyar. This decision turned out to be a boon for me as well, allowing me to continue my studies on Nangiarkoothu.

During this period, I had the opportunity to actively participate in the work at the Ammannur Chachu Chakyar Smaraka Gurukulam under the guidance of the great Guru Ammannur Madhava Chakyar. I consider myself fortunate to have been an inmate of the Ammannur Chakyar Madhom, where I deepened my knowledge of Koothu, Kutiyattam, and Nangiarkoothu.

Did Ammannur Asan teach Nangiarkoothu to Nangiars in those days?

In those days, it was not conventional for Chakyars to teach Sreekrishnacharitam Nangiarkoothu to Nangiars. Instead, Nangiars often trained their daughters. Due to a lack of encouragement for a long time, the training remained primarily ritualistic. Even Sreekrishnacharitam Attaprakaram was absent in many Nambiar Madhoms. Chakyars would train Nangiar girls to take on female roles in Kutiyattam. They were taught the Purappadu and, occasionally, the first few Slokas for their ceremonial Arangetram. Girls were required to learn Purappadu and present their maiden performance to be recognised as Nangiars. This ceremonial practice was as significant as Hindu customs like Jatakarman and Upanayanam.

Even in Irinjalakkuda, Kutiyattam had only a few female roles in those days. The Ammannur tradition taught these roles to a limited number of girls. However, Sreekrishnacharitam Nangiarkoothu, following the Purappadu, was seldom taught or practised, except during rare Adiyanthiram ceremonies in some temples.

Did you personally learn Nangiarkoothu from Asan?

My initial learning in Nangiarkoothu at Ammannur Chakyar Madhom was under the guidance of Dr Parameswara Chakyar, a well-known Sanskrit scholar and son of Kutiyattam maestro Ammannur Chachu Chakyar. After I obtained an Attaprakaram of Sreekrishnacharitam Nangiarkoothu, he taught me 4–5 Slokas daily and explained their meanings. This was my foundational training. I had not studied Sanskrit earlier, but this experience proved invaluable later. It took me six months to read and comprehend it.

Later, I had the privilege of being one of the first disciples of Ammannur Asan, where I learned the essence of the tradition. Other luminaries, such as Villuvattathu Kunhipillakutty Nangiar, Subhadra Nangiar, Sitha Nangiar, and Changamanattu Damodaram Nambiar, also contributed significantly to my study. We gathered additional information from Chathakkudam Nambiar Madhom and Kalakkathu Nambiar Madhom. Several workshops were also organised at Natanakairali.

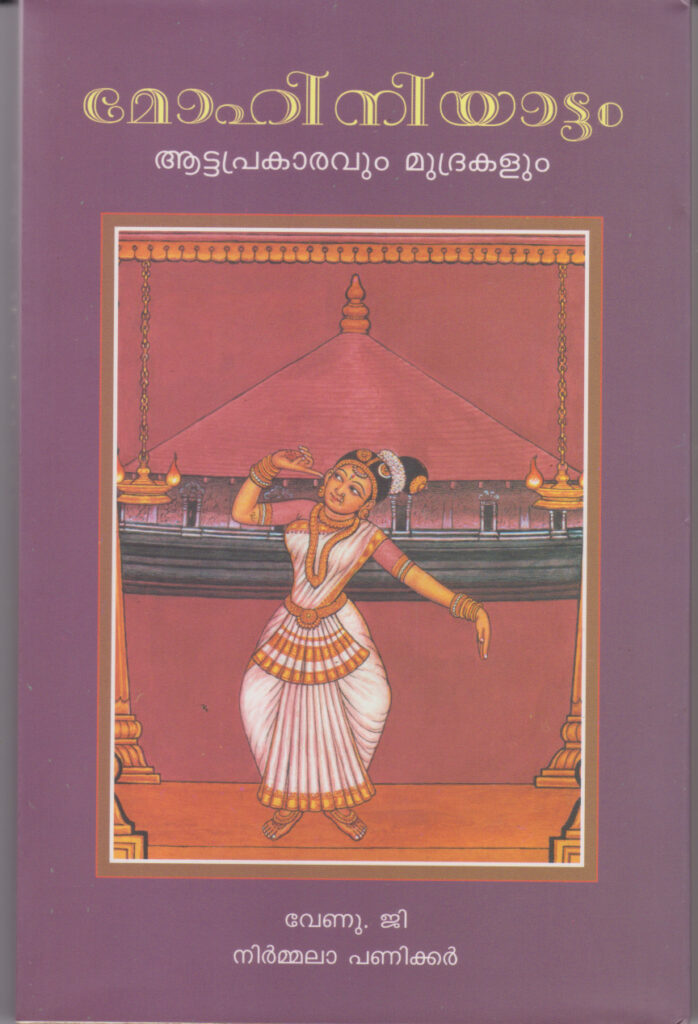

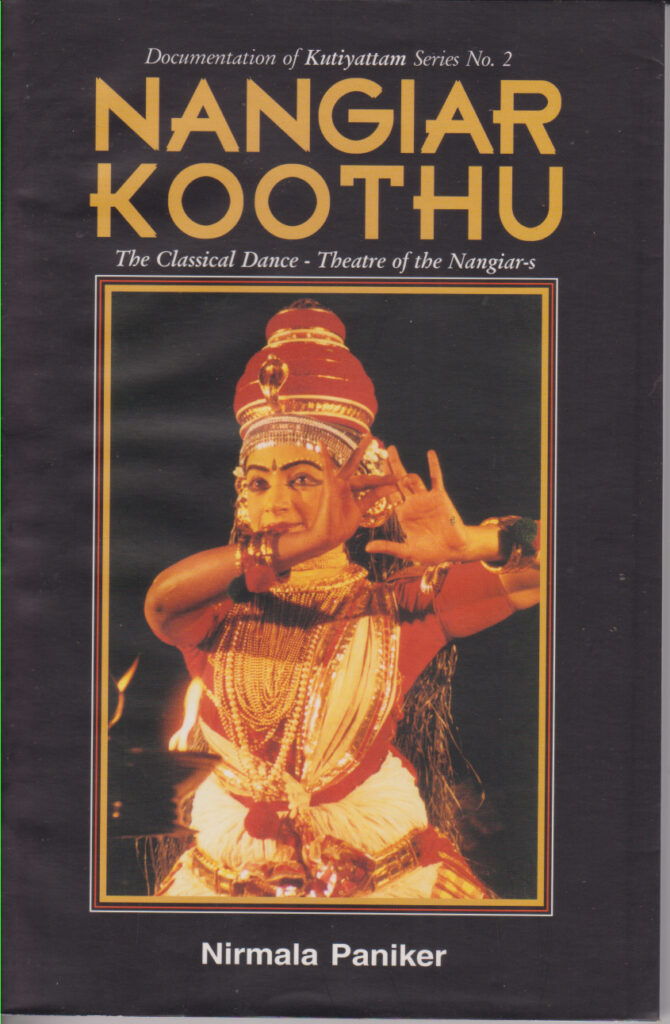

Compiling my learnings, I published the first monograph on this art form in 1992, titled Nangiarkoothu: The Classical Dance Theatre of the Nangiars.

Did Kalamandalam contribute to the revival of Nangiarkoothu?

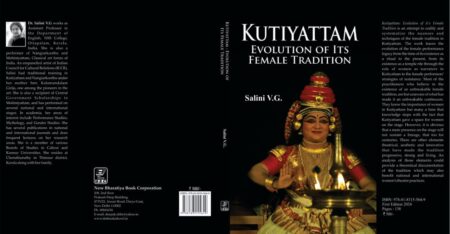

Kerala Kalamandalam established a Kutiyattam department in 1965 under the visionary Painkulam Rama Chakyar. In its initial decades, the department significantly enhanced the portrayal of female characters in Kutiyattam.

For the first time in the history of Kutiyattam, two girls, Girija and Sailaja, from non-Nambiar families, were selected and trained in female roles, including Purappadu and Udyanavarnana. Painkulam Rama Chakyar, along with Chutti expert Govinda Warrer, refined the costume, ornaments, and headgear for Kutiyattam actresses, making them more visually appealing.

The contributions of disciples such as Kalamandalam Girija, Sailaja, and Margi Sati brought female characters to the forefront of Kutiyattam performances. Additionally, the publication of the Sreekrishnacharitam Attaprakaram, compiled by Shri P. K. Narayanan Nambiar, greatly aided the revival of Nangiarkoothu.

1 Comment

Very informative article. Please give a footnote to the photos.