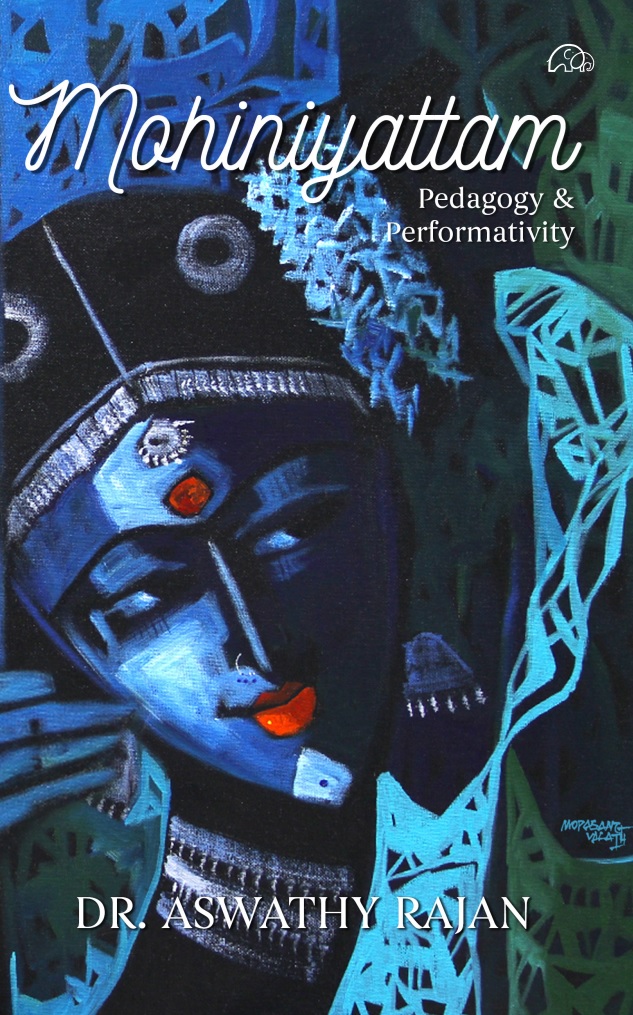

In her new book, Mohiniyattam, Pedagogy and Performativity, Aswathy Rajan explores the concerns around the way the Kerala dance form is taught today. She argues that it’s still under a feudal halo.

Aswathy Rajan claims commendable academic achievements in Mohiniyattam. She is the youngest author among the slew of authors of Mohiniyattam books. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in the Kerala dance form from Kalamandalam, and a masters in Kuchipudi from the Central University, Hyderabad with a first rank. Mohiniyattam: Pedagogy and Performativity is based on her doctoral thesis of 2020.

In the book, Rajan ventures into unexplored areas. Evidently, her focus is on how Mohiniyattam is taught. Commendably, her methodology is holistic. She puts forward seminal proposals that could become fodder for a healthy debate among the dance fraternity, art schools and among the aficionados in the days to come.

The book has seven exceptionally long chapters. Rajan opens with a graphic description of Kerala’s cultural setting through the ages. She looks into abominable practices such as Smartha Vihcharam, Sambamdham and the institution of Devadasis, which highlight how meanly women were treated in those days.

The first chapter, ‘A Feminine Cult of Dance Blooms’, is a serious study of the evolutionary history of Mohiniyattam. Referring to casteist ties, Rajan explains how the renaissance helped eliminate the barriers between Savarana and Avarna art forms.

The next chapter discusses the immense contributions of Swathi Thirunal, (‘Unto the Path of Institutionalization’). However, the quote of Sreedhara Menon, “He (Swathi) was also the one who designed the basic idea of the Mohiniyattam costume of the present-day”, is unconvincing. Kerala society’s attitude towards Mohiniyattam during the post-Swathi period is illustrated in Cheruvalathu Chathu Nair’s novel Meenakshi (1890), in which the dance form is listed as social malpractice!

How Mohiniyattam evolved

With all the concomitant anecdotes, the author describes the circumstances that led to the establishment of Kalamandalam. Rajan zooms in on how Mohiniyattam’s pedagogy changed due to its institutionalisation. She mentions Puraskaranam, an ancient tradition of teaching peculiar to Kerala. Under this system, the Guru would reside in the student’s home and take classes according to his/her convenience. Incorporation of some positive aspects of Puraskaranam, though obsolete now, in the Kalamandalam pedagogy may be progressive.

The third chapter is a clinical analysis of the attempts of individuals and the techniques they helped evolve. She begins with Kalamandalam Kalyanikutty Amma, followed by Sathyabhama, Kanak Rele and Bharati Shivaji. Rajan’s keen and unbiased observations bring to light the intrinsic features of the styles of the entire fraternity.

The next chapter deals with corporeal movements in Mohiniyattam. The writer, a dancer of repute, discusses techniques she has developed and according to her, the languidness that’s peculiar to Mohiniyattam provides additional opportunity to polish the recital in every aspect of Chaturvidhabhinaya.

The geometrical patterns of body movements, the influence of the Bhagavathy cult, movements in daily life such as the pounding of paddy, yoga, etc., have been explained in relation to the basic movements. While mentioning ‘Gender trouble Vs. Lasya Tantra’, she comments that “certain movements characterise the phenomenon of subjugation and domestication of female bodies”.

Making Mohiniyattam modern

However, she avers that the importance of Mohiniyattam could be rejuvenated by adding significant themes relevant to contemporary life. This could be achieved through a revitalization of music, costume and stage-setting, which can energise and uplift the dance form. The author corroborates the argument by elaborating the kutchery tradition and the repertoire in which aharya also matters. The book features an exhaustive and informative table on the landmark events in the evolution of Mohiniyattam.

According to Aswathy, the Performer, the Setting and the Spectator are the three crucial parameters that influenced the transformations and adaptations in Mohiniyattam. She discusses the triangular relationship among them convincingly, along with the nature and growth of spectatorship in Mohiniyattam from the days when the dance was performed to the deity, on the stage (proscenium), to a global audience through digital media. The corresponding change in the attitude of the dancers is remarkable. Using quotes from Bernard Shaw and Kulasekhara’s division of the audience into Prekshaka and Nanaloka, Rajan underscores the inevitability of quality spectators for the success of art.

The author repeats the historical aspects while addressing the concerns about the growth of Mohiniyattam. Classicization is another aspect dealt with in detail here. ‘Mapping Pedagogy’ in the various stages, the last being in the institution, also appears repetitive. The nuances listed spring from her own experience in Kalamandalam.

Worth mentioning are her own views in the last chapter, ‘Arguments, Apprehensions and Solutions’. The importance of dance teaching and the intrinsic qualities of a teacher discussed are significant, especially these days when dance has been elevated to the academic platform. She underscores the inevitability of teacher training as many institutes lack trained teachers. Good performers need not be good teachers, which is a reality. The points raised in ‘Resolutions’ on teacher training warrant the attention of the institutes concerned. But a suggestion of a scheme for moulding a teacher is missing.

Criticism on Mohiniyattam practice

While arguing that Mohiniyattam is still under the feudal halo, Rajan raises certain questions and points out, “Mohiniyattam could be a highly potential medium of human expression when it is free from attempts of recasting the mundane stories of ‘eros’ and ‘submissiveness’”. On her suggestion that Mohiniyattam should embrace themes such as caste discrimination and untouchability, I think at least a few of such choreographies have already been produced by exponents, mostly non-native.

Rajan launches her broadside on the ancient treatises and the practice of strictly adhering to the tenets. But such texts are only guidelines and they guarantee freedom for appropriate innovations in tune with the demands of the times. Natyasastra is an example. Disputing the opinion of a dancer that a sense of aesthetic taste is a must for commoners to digest the intricacies of Mohiniyattam, Rajan argues that a commoner could really become a good spectator or rasika if she/he is a daily concert-goer. This sounds hypothetical.

Commercialisation and marketing techniques that performers use to attract the uninitiated audience has affected the pedagogical arena, she points out. Further, she holds that the increase in the intake of students in institutes is a reflection of the same. The proposals she lists in the categories Idea, Objective and Productivity deserve active consideration of the functionaries of the training institutes.

By Aswathy Rajan

Ivory Books, Thrissur

288 pages; Rs 350

While discussing the ‘Anti-discrimination and Human Rights Law’, she states, “Gender, race, caste, body-bullying and discrimination are evidently active in the terrain of dance training institutes of the state”. This is far from reality since the reservation of seats for lower castes is strictly followed in institutes such as Kalamandalam. She reiterates that discrimination exists in the selection of students for performances as well. These aspects demand a thorough verification and prompt comments from the authorities of Kalamandalam.

‘Kalari Memoirs’, an additional piece that appears last, is a candid expression of her experiences in her alma mater. She is critical of the ‘fear-factor’ drilled into the brain by the teachers and also ahangharam (arrogance) “a word heard aplenty times during our course”. These, though a part of the traditional setting of classical dance learning, could be counterproductive to the creativity of the dancer, she feels.

Clearly, the author has benefitted from the wide exposure she has enjoyed outside Kerala and this is reflected in the writing of the book. However, one feels the editing could have been tighter. Typos could have been taken care of more diligently. The diagrams appear much reduced in size and therefore lack clarity and visibility.

Write to us at [email protected]