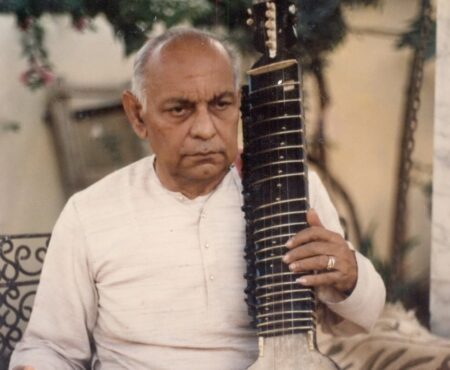

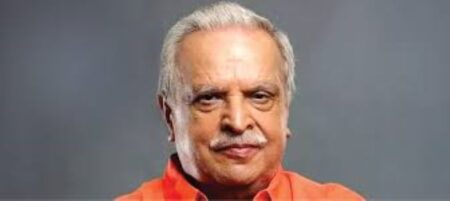

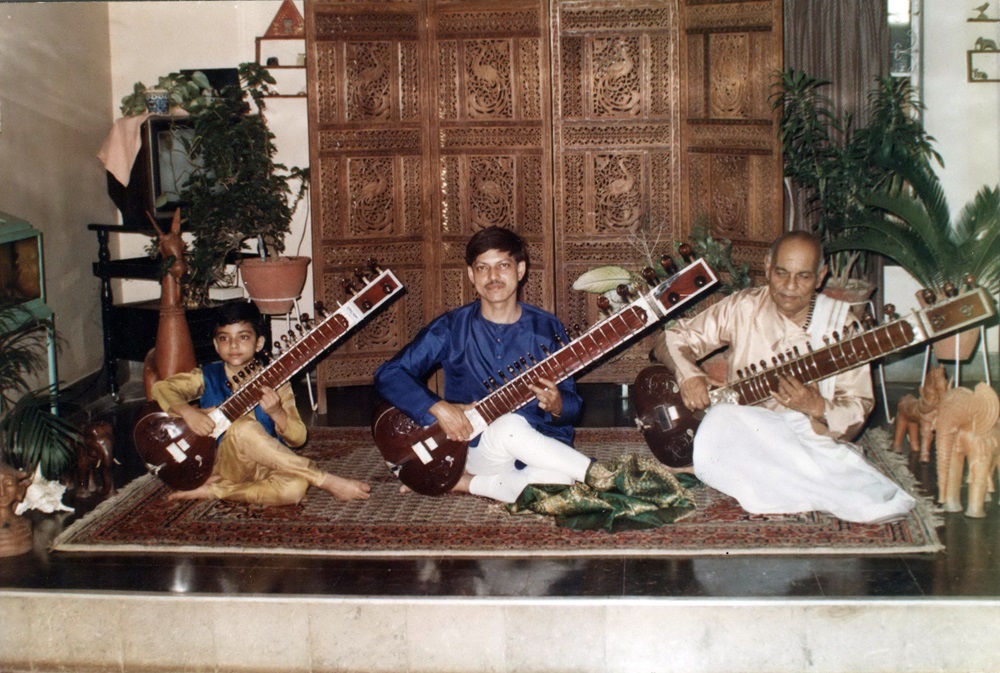

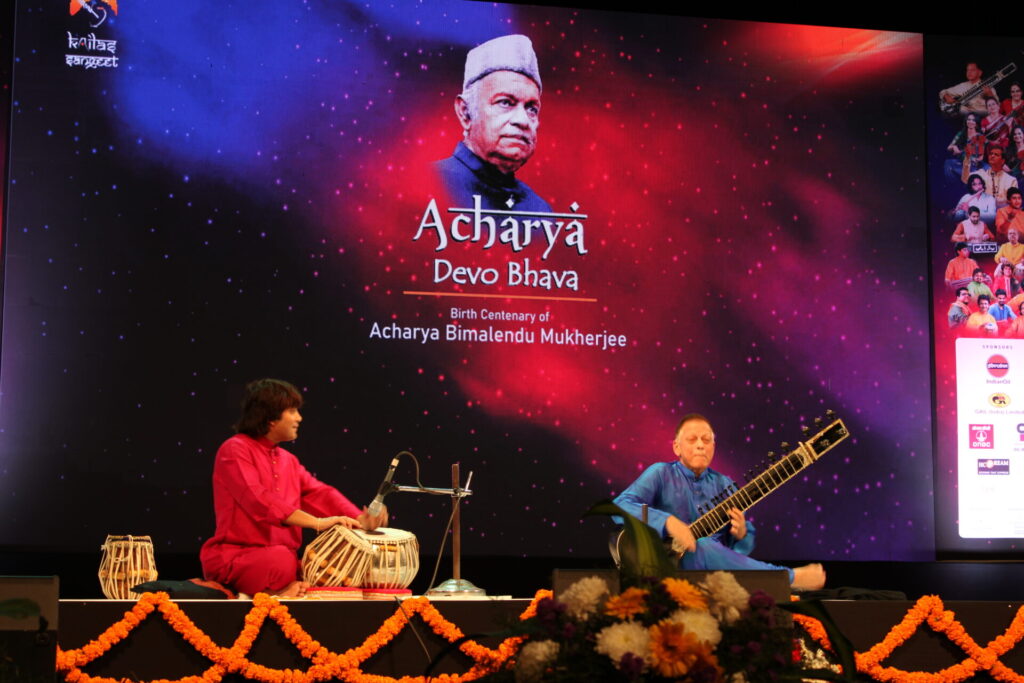

When Pandit Budhaditya Mukherjee, torchbearer of the Imdadkhani gharana and son of the legendary Bimalendu Mukherjee, sits down with his sitar, the instrument ceases to be a mere tool—it becomes an extension of his being. With eyes closed and spirit open, he surrenders to the moment where melody, rhythm, and emotion coalesce into something ineffable. His music is not about mastery alone; it is about merging with the raga’s will, letting the unconscious lead the way as phrases blossom unbidden from a vast inner reservoir—his “riyaz-bank,” as he calls it.

In this freewheeling conversation, Pandit Budhaditya Mukherjee reflects on his lifelong pursuit of the perfect sound—one he first heard as a child in Vilayat Khan’s Khamaaj—and the painstaking decades it took to shape a sitar that could give voice to that elusive dream. He speaks of the invisible dance between conscious craft and unconscious surrender, of the sanctity of saath-sangat, and the quiet genius of a tablist who lets rhythm float rather than dominate.

Approach to a raag

I swim in the aesthetics of the raag, which speaks to me and create its own image before I consciously get to know it. The moment I am conscious I become an interference. In the unconscious zone the raag tells me, “Touch me like this. Hold me like this”. If my unconscious mind fails to perceive that, then my music falls apart.

Negotiation between the conscious and the unconscious

The conscious and unconscious constitute 3% and 97 %, I would say. The movement between them becomes dynamic and then, I do not know what my sitar plays. When I play music now, I have no work. I am at ease. The sound of my sitar is doing all the work. When a phrase takes shape, it happens on it’s own and when a similar phrase takes form again, it comes in a different placement. So, I am only swimming from moment to moment, wisely enough, so as not to disturb the beauty of the raag. I should play within the frame; there is a transparent glass-like frame, and I should be careful enough not to bombard and break it.

Role of emotion

Emotion is everything; emotion is the passion, so to say. The raag is creating a certain ambience that is flowering and I will be fusing that into the rhythm.

While one’s emotion, taiyaari and wajan are all present, the sangatkaar’s part is vital, in keeping the mind floating in the rhythm, so that the player does not sink or run away from the scene. While rhythm is extremely beautiful, it’s prominence should not become a burden and disturb the mind of the music-maker.

There lies the sangatkaar’s genius. I live my music on his theka. And the lustre of his tabla-beats keeps my mind on the rails of beauty. All this together builds a zone of comfort where I can create my music better. And preferably, if you do not know what you are creating, I feel, you will create better.

Knowledge is wonderful no doubt but knowledge must not translate itself into interference.Before I take the dive into creation of aesthetics in a particular way, spontaneity comes when the right passion has been ignited to the right degree.

Path to that kind of passion-building

It is the raag. The passion is built by the raag, not me. I am a mixer, in which the raag and other necessary elements are churned and my beautiful manifestation results from this process. One’s taiyari is just one more ingredient there. Even with magnificent taiyari, if only that facet were to stand out, it would still result in poor quality. When we are young and hot-blooded, taiyari seems like a colossal thing to achieve and it is natural at that age.

With growing age, I realise that while virtuosity is necessary for expression, it should be like a lightning that lights up things around. But if the lightning hits hard, that is the end of things. Even a taan should take form this way, and when it gets fused into a composition, it gives rise to a rare beauty. In a way, one piece of beauty leads to another and then yet another, and they all get latched together exquisitely.

Your dream-sound

Yes, my dream-sound. But, thank God, my dream sound existed all along, and it exists even today! Now my dream-sound has been realised. In fact, the sound just happened by fluke, through the hands of a famous sitar-maker of the 1940s, Kanhaiya Lalji of Calcutta. This endorses my belief: Time is God, God is time. Around 1954, I think. I came to know of this incident through my father.

At Calcutta, in an open-air program Ustad Vilayat Khan’s sitar got so wet that he could not play it. One of his father’s disciples, Biru Mitra Babu offered his sitar for playing. So, he played and this sitar was not returned at all. He took it away with him. Many sitars that looked like it got made, but none that replicated the same sound. There was no process that could replicate the sound. Sitar-makers have a certain vision while making instruments. While they can make instruments that look alike, they cannot recreate the sound quality.

Your search for your dream-sitar

I arrived at that image after hearing that sitar when I was seven, and now I am seventy. It was the same sitar..Vilayat Khansaab’s sitar playing exceptionally sweet, melodious music((1961-raag Khamaaj) and I felt like going back to it again and again. At that age, what is beautiful sits easily in a child’s mind in a pure state. And it stayed with me. I handled many sitars, but no; not that kind of good sound.

But my desire was clear. I was getting lots to learn at home from the loveliest and the greatest guru, my father, teaching with immense love, affection and compassion. God had bestowed me with everything but not the sound of the sitar that I desired.

In fact, my state was exactly this: I want a sound and I have a sitar, but they are not matching; hence my passion is not served. What do I do? One option was to give up the sitar. But no, I was in love with the sitar. What is the next best thing, I wondered! A chamber must have been created in my unconscious mind where the sound that was not acceptable to me was getting filtered. Like a filtration plant, an aesthetic filtration was happening in mymind. I stopped listening to the sound that was not appealing to me but perceiving the sound that I desired, which was not the reality.

I changed nine sitars in 22 years. I was probably not lucky enough and I was getting frustrated. At 40, I was playing hundreds and hundreds of concerts. Still unhappy, my mind was getting tired due to the filtration process and that was draining a lot of my energy. If that were avoided, I could access my passion better. There was no one that could help me. The only option left was: Do it yourself! But I knew no carpentry or the skills of instrument-making.

The challenge was peculiar. The challenge was how to communicate my aesthetic desire to another person. How to describe the exact sound that I need? A chance meeting with Chandi Charan Mandal, a professional sitar-maker worked the magic. He came across as a very amicable person and finances were discussed. Our minds matched and the journey began. While I had an uncommunicable dream, Mandal had to work in a directionless state. The situation was strange but the passion was real.

The sitar was ripped open but what to do next was an unknown. Ruining things on hand and creating bad sounds was a lesson in itself. It brought clarity about the road not to be taken. Two sitars were dissected and rebuilt on opposing principles. A third was built based on lessons learnt and the uncertain journey took years. Improvements in small doses brought hope and Chandi Babu could replicate these strokes on my performance sitar, which I finally put to test on the concert platform.

At great risk, I performed on the testing ground, with a pack of unknowns up my sleeve. We finally arrived at the process to create the desired sound based on our own experience. The success rate of replication was at a minimum of 90 percent, the 10% depending on the quality of material, weather condition etc. With Chandi Babu’s passing, the process came to a halt. Five to six sitars from that period are in the hands of my disciples, and their playing certainly reflects the joy that they draw from those sitars. In fact, the realisation of my dream-sound has been my greatest achievement in music!

My wife Nabanita’s steadfast support in realizing this dream was exceptional. To others, it perhaps seemed like a crazy pursuit..

You have thousands of concerts to your credit in India and all over the world. Your experience with listeners..

Indian listeners are already exposed to our music and acquainted with the pleasures that are going to come, but not others. However, our classical music is unique because it is the closest to human emotions, because of the variety of raags. The reading and interpretations can vary across the world but emotions, the navarasas are the same.

Your celebrated performance at the House of Commons in 1990..

I was the first artist in the history of the world to perform at the House of Commons, London. The event was held in the Visitors’ Room across the corridor, a very beautiful space indeed. I was accompanied by Pandit Anindo Chatterjee on tabla. The impeccable, immaculate silence of participation by the listeners was highly impressive. Silence speaks at the right moment and I received that gesture.

What more could I ask for? An artist has a great responsibility in that situation. My effort for that concert was to keep up the esteem of Indian classical music and music did the rest. Summing up his present state of mind during a performance, Panditji shared, “I am now speaking at a level when I have removed myself from the scene. When I am physically playing there, the raag is speaking to me. I have a sitar which is giving me that lustrous sound which helps in igniting my passion.”