Qila Mubarak reveals Patiala’s heritage to eclecticism comprising Sikh, Rajput and Mughal architecture. The 18th-century merits the earliest restoration.

Amid Covid-19 that has forced a temporary closure of several historical monuments across India, the Qila Mubarak in upcountry Patiala appeals as a cultural icon from the 18th century. The royal city in present-day Punjab state is mostly known for its traditional jutti footwear and colourful salwar clothing, besides the parandas that are tassels to braid hair. Then, of course, there is the (somewhat infamous) Patiala Peg, which is an amount of whiskey measured by a strange yardstick.

Beyond these exists a hidden gem. And that, at the heart of the Old City. It’s a two-and-a-half-century-old fortress, not exactly in good shape. In fact, the World Monuments Fund cites Qila Mubarak as among the world’s 100 most endangered sites. It’s another matter most visitors don’t know about the certification by the Washington-based non-profit organization involved in the preservation of heritage sites the world over.

Qila Mubarak features an architecture that an amalgamation of the Sikh, Rajput and the Mughal. Baba Ala Singh, as the first king of the princely Patiala state, laid its foundation in 1763. What subsequently emerged as a majestic structure remains today a bit hidden in sight, engulfed by major market areas. Yet, one instantly gets pulled into the old-world charm. That is once you get into the complex through the arched opening.

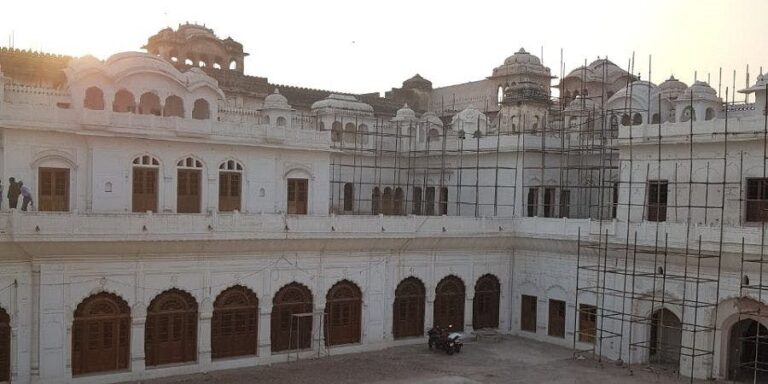

Only on entering the complex through its gateway of elegant masonry does one realise the scale of Qila Mubarak. The structure is gigantic. It takes one’s breath away with its stuccowork in plaster, finely sculpted balconies, towering walls and rustic wooden doors. The complex consists of various buildings, namely the Qila Androon (residence of the royals), Darbar Hall (from where the royals ruled), Ran Vaas (Royal guesthouse), Sard Khana and Jalaun Khana.

Up until the first half of the 20th century, locals used to participate in the events and activities at Qila Mubarak. Now, this connection between the residents of the town and the form has itself receded into the annals of history. Even so, the rich architectural and cultural heritage retain a charm for the discerning.

The eastern courtyard or palace was meant for public use. Here, the royalty engaged with the public for performing arts and music. On the other hand, the courtyard on the west side was private.

Beautifully crafted columns and corridors connect all of the complexes to each other. Most rooms are clustered around courtyards. White cupolas on the top of the Qila provide a panoramic view of the whole city.

The buttresses, spread all across the fortress, bring attention to the need for the earliest restoration. True, INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage) has done some preservation efforts. These include the conservation of wall paintings in the complex. Experts have taken steps to ensure no alteration to the distinctive characteristics of the fortress.

Qila Mubarak’s charm is not just limited to its architecture. It also houses paintings with Sikh subjects and depictions from Hindu mythology, adopting a liberal approach. Qila Androon, consisting of 13 royal chambers, houses paintings in the Patiala Art style.

In 2004, Ran Vaas lost 200-year-old miniature paintings (worth millions in the international market) to theft.

Today, one highlight is a set of three miniature paintings, depicting Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh in various moods. Also, elaborate paintings of flora and fauna, figurative narratives and geometric patterns can be found on the interior walls of chambers. The Darbar illustrates Vishnu avatars and stories of courage, while the ladies’ chambers feature illustrations of romantic epics. Some chambers also consist of artworks depicting qualities of a king — good or bad.

In addition, there is intricate mirror work. A small part of it consists of Gothic arches and a roof of Mughal and Rajasthani styles. It is also the home of impressive murals, which artisans of Rajasthani, Pahari and Avadhi descent created in the second half of the 19th century. According to local legend, the kitchen at Qila Mubarak, known as Lassi Khana, could feed up to 35,000 people. Astonishingly, the fortress has an underground sewerage system and a room connected to a tunnel that brings cool air from the basement. For recreational purposes, it also consists of a Putli Ghar (Pupper house) and Bagh Ghar (Garden House).

The door to the Complex faces Adalat Bazar, which begins from the Qila and ends at the Anardana Chowk. The roundabout close to the fortress is known as Qila Chowk and it is often filled with people. Most shoppers won’t even give a second glance to the Qila here, because it doesn’t look like much from the outside. Fortunately, the artwork on the outer walls is also being restored.

Qila Mubarak is situated in the oldest part of Patiala. The whole city developed around it. Naturally, it holds a lot of history. This Qila has been the residence of Maharaja Sahib Singh (1781-1813), Maharaja Karam Singh (1813-45) Maharaja Narinder Singh (1845-62), giving it immense heritage value.

On the whole, the place forms an epitome of the Indian aesthetic, symbolic of the secular nature of the area with influences on the architecture from all over the subcontinent and remnants of colonization.

Aditi Bhaskar is a journalism student based in Bengaluru